The Woman Who Challenged the Idea that Black Communities Were Destined for Disease

A physician and activist, Rebecca J. Cole became a leading voice in medical social services

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/57/2a57c574-d756-4989-8aff-bc6596e50b9e/lesliesanatomyroom.jpg)

In the late 19th century, the idea that disease and death proliferated in poor black communities was taken as a given, even among doctors. Physician Rebecca J. Cole, one of the first black women doctors in America, pushed back against this racist assumption over a 30-year career in public health. As both a physician and an advocate, she worked to give her own community the tools and education they needed to change their circumstance, inspiring generations of doctors who focused specifically on black communities.

“We must teach these people the laws of health; we must preach this new gospel,” Cole wrote in an 1896 issue of the periodical The Woman’s Era. That gospel, she continued, was that “the respectability of a household ought to be measured by the condition of the cellar.” That guidance may seem simple enough today—a house with a clean cellar instead of a rotting one is healthier for its inhabitants—but its real significance was to challenge the long-standing widespread belief that disease and death were hereditary in black people.

Cole was born in Philadelphia on March 16, 1848. Though not much is known about her childhood, medical historian Vanessa Northington Gamble learned from census records that her father was a laborer and her mother, Rebecca E. Cole, was a laundress; she was the second of four children.

Cole attended the Institute For Colored Youth, the only school for both girls and boys of color in the state. The Institute was chartered by Pennsylvania in 1842 with the express purpose of training black youth to be teachers of their black communities. Cole excelled academically: she was even awarded $15.00 upon receiving her high school diploma for “excellence in classics,” according to the Institute’s 1863 annual report.

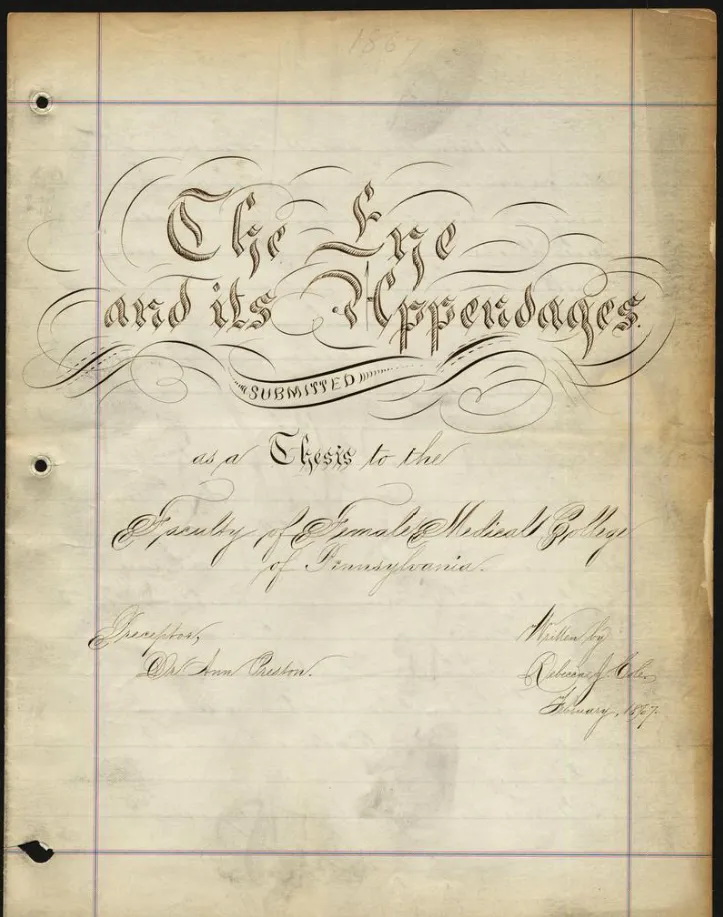

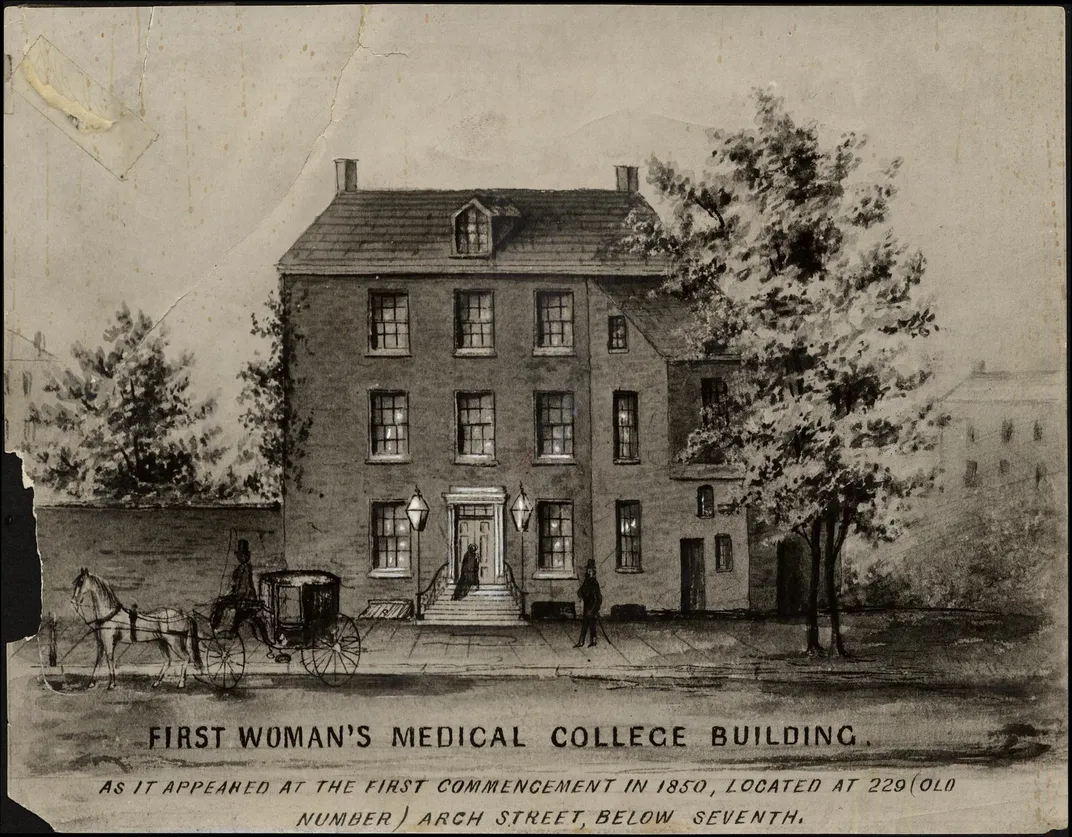

In 1864, a year after graduation from the Institute, Cole matriculated into the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMC), the first school in the U.S. to award women the degree of Medical Doctor. (At the time, only an undergraduate degree in medicine was required to become a physician; it wasn’t until after World War I that today’s four-year medical school with residency became a requirement.) Upon completion of her thesis, titled “The Eye and its Appendages,” Cole graduated in 1867, becoming the first black woman to graduate from the college and the second black woman physician in the U.S.

Cole was in an early vanguard. Three years earlier, Rebecca Lee received her medical degree in 1864 from the New England Female Medical College in Boston; three years after, in 1870, Susan Smith McKinney received hers from the New York Medical College for Women. Historian Darlene Clark Hine writes that “Lee, Cole, and Steward signaled the emergence of black women in the medical profession.” These three women ushered in a generation of black women physicians who worked to make medicine accessible to black people through community based healthcare.

Between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the turn of the 20th century, Hine has been able to identify 115 black women physicians. The establishment of women’s medical colleges and black colleges were essential to the training and success of black women physicians. But integration, with all its benefits, had a catch: by 1920, many of these colleges had shuttered and with the increasing number of integrated co-educational colleges, the number of black women physicians dwindled to only 65.

In the early days of her medical career, Cole trained with some of the most notable women physicians of the day. At WMCP, Ann Preston, a leading advocate of women’s medical education and the first woman appointed dean of the college, served as Cole’s supervisor. Cole continued on to become resident physician at the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children, founded and run by Elizabeth Blackwell—the first woman to earn a medical degree in the U.S.—and her sister Emily. Staffed entirely by women, the Infirmary provided comprehensive healthcare, including surgical procedures, to the city’s poor and underserved.

It was here that Cole found her passion for providing much-needed medical services to underserved communities, known as medical social services. At Blackwell’s Tenement House Service, a one-of-a-kind program for disease prevention that the Infirmary began in 1866, Cole served as a sanitary visitor whose goal was to “give simple, practical instruction to poor mothers on the management of infants and the preservation of the health of their families” in Blackwell’s words. Blackwell went on to describe Cole as “an intelligent young coloured physician [who] carried on this work with tact and care.”

After New York, Cole practiced medicine in Columbia, South Carolina. Though the details of her time there are scant, an 1885 article from the Cleveland Gazette said that “she held a leading position as physician in one of the institutions of the state.” Sometime before the end of Reconstruction, Cole returned to her Philadelphia home and quickly became a well-respected advocate for black women and for the poor. Darlene Clark Hine writes that “[r]acial customs and negative attitudes toward women dictated that black women physicians practice almost exclusively among blacks, and primarily with black women, for many of whom payment of medical fees was a great hardship.” Cole did this to great effect.

Excluded from hospitals and other medical institutions, black women paved their own way by establishing their own practices and organizations within their communities. Combining the knowledge and skills she acquired in Blackwell’s Tenement House Service and her lived experience within Philadelphia’s black community, Cole founded the Woman’s Directory with fellow physician Charlotte Abbey. The Directory provided both medical and legal services to destitute women, particularly new and expecting mothers, and worked with local authorities to help prevent and fairly prosecute child abandonment.

At the turn of the 20th century, tuberculosis posed a particular problem for black communities. Even as rates of infection went down among white people, they shot up among black people. Not all physicians agreed on the cause of this disparity. “There was a belief after the Civil War that the enslaved had never had tuberculosis, and it was only after the Civil War that you see more cases of tuberculosis in black people,” Gamble says in an interview with Smithsonian.com. “So the question was: why is that?”

In the journal article “Culture, Class, and Service Delivery: The Politics of Welfare Reform and an Urban Bioethics Agenda,” Gerard Ferguson shows that physicians refused to treat black communities based on a prevailing belief that disease was inherent and—so treating them would only waste public resources. “You find some physicians who said it was something inherent in the bodies of Africans, that their lungs might be smaller, that their bodies were frail, and that tuberculosis was going to solve the ‘race problem,’” says Gamble.

Even black physicians observed that there tuberculosis was more prevalent after slavery—but the difference, Gamble says, is that “they pointed to social conditions.” Civil Rights leader and sociologist W.E.B. DuBois adopted a sociological approach, looking at how social conditions contributed to disease, but he also he argued that one reason for the high rates of tuberculosis among black people was their ignorance of proper hygiene.

Cole, however, did not see the problem as stemming from ignorance in black people so much as a failure of white physicians to treat infected black people. “[H]osts of the poor are attended by young, inexperienced white physicians,” she wrote in response to DuBois in the periodical The Women’s Era. “They inherited the traditions of their elders, and let a black patient cough, they immediately have visions of tubercles... he writes ‘tubercolosis’ [sic] and heaves a great sigh of relief that one more source of contagion is removed.”

She went further, challenging discriminatory housing practices and opportunistic landlords that kept black people living in unhealthy conditions and thus made them more prone to contagious diseases—justifying their continued oppression. Cole in turn advocated for laws that regulated housing that she called “Cubic Air Space Laws”: “We must attack the system of overcrowding in the poorer districts …that people may not be crowded together like cattle, while soulless landlords collect 50 percent on their investments.”

Cole’s understanding of the interplay of racial inequity and health was prescient. More current research shows that social inequality, not biology, is to blame for most racial-health disparities. Cole’s medical work, in combination with the sociological work of scholars like DuBois, helped to establish a “multifactoral origin of disease and in the process undermine monocausal and reductionist explanation for disease that emphasized inherent biological and behavioral characteristics,” Ferguson writes.

For Gamble, this debate illustrates how Cole combined her insight on the intersection of health, race and poverty: “When she calls out physicians for their racism because it adversely affected the health of black people, it shows that our discussions about health inequities and the people who are fighting against these inequities goes much further back than we talk about today.”

Later that year, Cole joined two generations of black women activists in Washington, DC to organize the National Association of Colored Women in Washington. Late historian Dorothy J. Sterling identified Cole among the many the pioneering women who played key roles including anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells and abolitionist Harriet Tubman.

In 1899, she took up a post as the superintendent of the Government House for Children and Old Women that provided medical and legal aid to the homeless, particularly children. She closed out her career in her hometown of Philadelphia as head of house for a Home for the Homeless, a post she took up in 1910 and held until she died in 1922. A large part of her legacy is that “[s]he thrived and created a career at a time where she saw no physician who looked such as she,” says Gamble. “The importance of combining medicine with public health, and her emphasis on the social aspects of medicine, shows that medicine does not live in a bubble.”