As the World Faces One of the Worst Flu Outbreaks in Decades, Scientists Eye a Universal Vaccine

A universal flu vaccine would eliminate the need for seasonal shots and defend against the next major outbreak

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/9b/d79bc2f8-b3b7-4224-82dc-29d6bad8115d/48545962716_244ea13d2c_k.jpg)

With the deadly 2017-2018 flu season still fresh in public health officials’ minds, this year’s outbreak is shaping up to be just as severe. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), says this flu season could be one of the worst in decades. “The initial indicators indicate this is not going to be a good season—this is going to be a bad season,” Fauci told CNN earlier this month.

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that there have been at least 9.7 million cases of the flu since early October. The CDC has also been tracking flu mortality, reporting at least 4,800 flu-related deaths this season. The young, elderly and immuno-compromised are especially susceptible to the flu—this season, 33 children have died from the virus.

Even in mild cases, the flu virus can cause unpleasant symptoms like high fevers, muscle aches and fatigue. To protect yourself against the annual flu outbreak, public health officials have a simple piece of advice: get your flu shot.

While the flu shot is the best defense currently available against seasonal influenza, it is not 100 percent effective. The CDC reports that the influenza vaccine typically reduces the risk of illness by between 40 and 60 percent, and that’s only if the viruses included in the vaccine match the subtypes of influenza circulating that season.

As an RNA virus, influenza has a high tendency to mutate, Fauci told Smithsonian. Even within subtypes of influenza, the virus’s genetic code is constantly mutating, causing season-to-season changes that scientists call antigenic drift.

“Most of the time, the virus changes just enough from one season to another so that last year's flu isn't exactly the same as what this year's flu is,” Fauci says. “In order to get optimal protection, you recommend vaccinating people every year. That's very unique. There really is no other vaccine that you recommend somebody getting vaccinated every single year.”

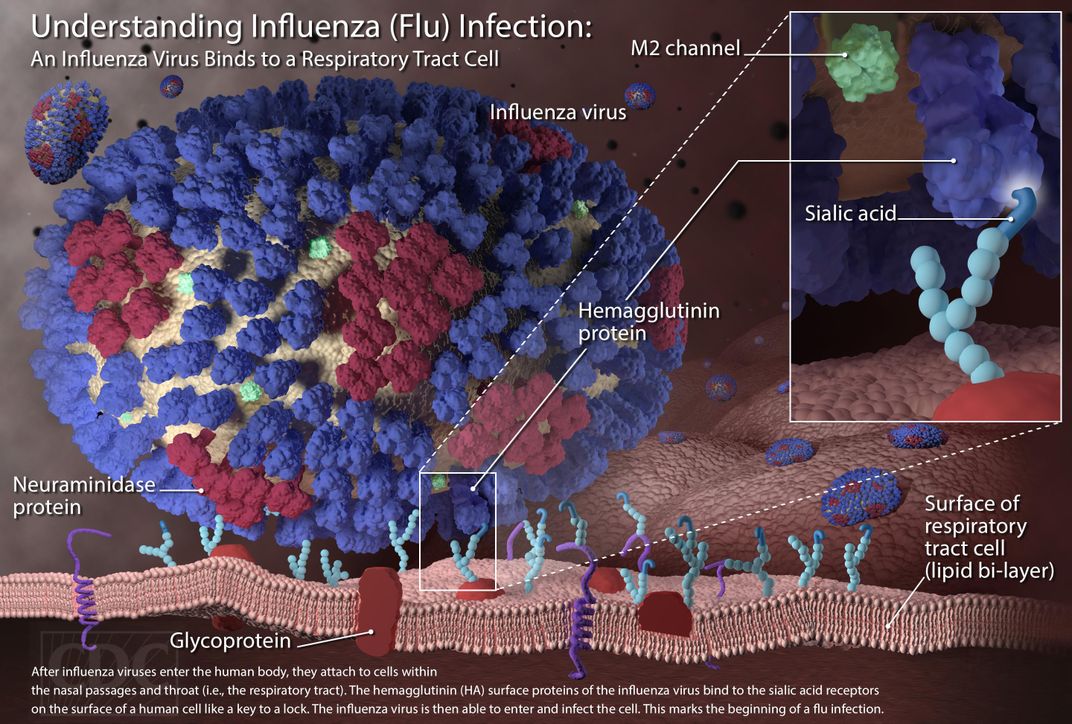

To keep up with antigenic drift, scientists are constantly tweaking the flu vaccine, which is designed to respond to a surface protein called hemagglutinin, targeting what Fauci calls the “head” of the protein. “When you make a good response, the good news is you get protected. The problem is, the head is that part of the protein that has a propensity to mutate a lot.”

The other end of the protein—the “stem”—is much more resistant to mutations. A vaccine that targets the hemagglutinin stem has the potential to provide protection against all subtypes of influenza and work regardless of antigenic drift, offering an essentially universal defense against the flu. NIAID, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is currently working to develop a candidate for a universal flu vaccine in a Phase 1 clinical trial, the first time the vaccine candidate has been given to people. Results on the safety and efficacy of the vaccine are due in early 2020.

Along with protecting against the seasonal influenza, a universal vaccine would also arm humanity with a weapon against the next pandemic strain of the flu. Flu pandemics come along occasionally and unpredictably, usually when a subtype of influenza jumps from animals to humans. This phenomenon, called antigenic shift, introduces a flu so novel to humans that our immune systems are caught entirely off guard.

The most severe flu pandemic in recorded history was the 1918 influenza, which infected one-third of the world’s population and claimed at least 50 million lives. The first outbreak of illness occurred at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas, in March 1918, according to the CDC. Genetic evidence suggests the particular virus came from a bird. The deployment of troops to fight in World War I contributed to the spread of disease, and at the conclusion of the war, the flu’s death toll surpassed the total number of civilian and military casualties due to the fighting. Unlike the seasonal flu, the 1918 pandemic was fatal for many otherwise healthy adults aged 15 to 34, lowering the life expectancy in the United States by more than 12 years.

Kanta Subbarao, director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza, says there are three criteria for a strain of influenza to be considered pandemic: novelty, infectiousness and ability to cause disease. “If a novel virus emerges, we need to know two things,” she says. “What is the likelihood that it would infect humans and spread? But also, if it were to do that, how much of an impact would it have on human health?”

The infectiousness and severity of impact can dictate whether a pandemic turns out to be relatively mild, like the 2009 swine flu, or as brutal as the 1918 epidemic.

Sabrina Sholts, curator of the exhibition “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, says the human activities that drive the emergence and spread of disease—like living in close quarters and traveling around the globe—have only intensified since 1918. But while globalization can escalate the transmission of disease, it can also facilitate the worldwide dissemination of knowledge.

“Now, we have a means to monitor and coordinate globally that didn't exist at that time [in 1918],” Sholts says. “I think that that communication is a tremendous tool, and that's an opportunity to respond rather quickly when something like this happens.”

Subbarao points to the WHO’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) as one example of global cooperation on flu research. She estimates that there are about 145 national influenza centers in 115 countries monitoring seasonal influenza, as well as any flu viruses that manage to jump from animals to humans.

In a statement in March, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus announced a Global Influenza Strategy for the upcoming decade. The strategy has two overarching goals: to improve every country’s preparedness to monitor and respond to influenza and to develop better tools to prevent and treat influenza. Research on a universal vaccine could support the second objective of arming the global population with a stronger defense against the flu.

“The threat of pandemic influenza is ever-present,” Ghebreyesus said in the statement. “We must be vigilant and prepared. The cost of a major influenza outbreak will far outweigh the price of prevention.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Daily-Staff-Photos-by-Noah-Frick-Alofs-3620-317x475.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Daily-Staff-Photos-by-Noah-Frick-Alofs-3620-317x475.jpg)