Insects are among Earth’s most abundant life forms, representing a staggering 80 percent of all animal species. But in recent years, reports of dwindling bug populations have led some experts to warn of an impending “insect apocalypse.”

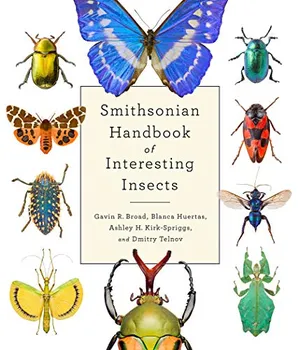

The Smithsonian Handbook of Interesting Insects, released earlier this spring by Smithsonian Books, aptly demonstrates why such an “apocalypse” represents a devastating blow to biodiversity. Compiled by entomologists Gavin Broad, Blanca Huertas, Ashley Kirk-Spriggs and Dmitry Telnov, the work spotlights more than 100 insect species drawn from the London Natural History Museum’s collection of some 34 million specimens.

Presented in stunning full-color photographs, the book showcases a range of insects, including the stalk-eyed fly, which has eyes at the ends of its long, protruding, antler-like stalks, the bright yellow-and-black ichneumonid wasp and the metallic golden-green weevil. Images are accompanied by short descriptions of the bugs, as well as information on their geographic distribution and size.

“We humans see insects like small creatures,” says co-author Blanca Huertas, the museum’s senior curator of Lepidoptera. “However, the size of insects transcend[s] to their incredible power to adapt to most habitats, including the most challenging ones, ensuring their ... success living on the planet even before humans.”

Interesting Insects’ publication coincides with the release of a study suggesting the aforementioned “apocalypse” is more nuanced than previously thought.

For the paper, newly published in the journal Science, researchers reviewed 166 surveys of 1,676 sites around the world. The analysis showed that Earth’s land-based bug populations shrank by 27 percent over the past 30 years—a rate of just under 1 percent per year.

Earth’s dwindling insect numbers can’t be attributed to a single driving factor. Instead, studies show bugs face an array of threats, including habitat destruction and fragmentation, climate change, pesticides, urbanization, and light pollution.

“The decline of [i]nsect populations is real, but it has been measured only in few areas of the world,” says Huertas. “Ironically, the less studied areas in the world [hold] the biggest diversity of insects (and many other organisms), so the problem is bigger [than] we think (and know).”

Gavin Broad, principal curator in charge of insects at the museum, adds, “Our hope is that by drawing attention to some of the amazing variety of insect life, people will appreciate a bit more the explosion of color and form at the tiny scale. And that acting to conserve the natural world will help ensure this diversity of life continues to thrive forever, rather than only being known from old museum specimens.”

To mark the release of Interesting Insects, Smithsonian magazine has revived a handful of the featured insect species in the form of short GIF animations. Up first: an artistically inclined butterfly named after one of the giants of modern art.

Picasso moth

Scientific name: Baorisa hieroglyphica

Distribution: Northern India, Southeast Asia

Size: 50 mm (2 inch) wingspan

The species name hieroglyphica refers to the striking geometric lines and shapes on this moth’s fore wings. Perhaps the shapes resemble a red insect head with antennae and legs, directing a bird’s bill toward the wingtips? Or a spider on its web? Although sometimes referred to as the Picasso moth, you might think Miro moth—a nod to Spanish painter Joan Miró’s colorful creations—is more appropriate.

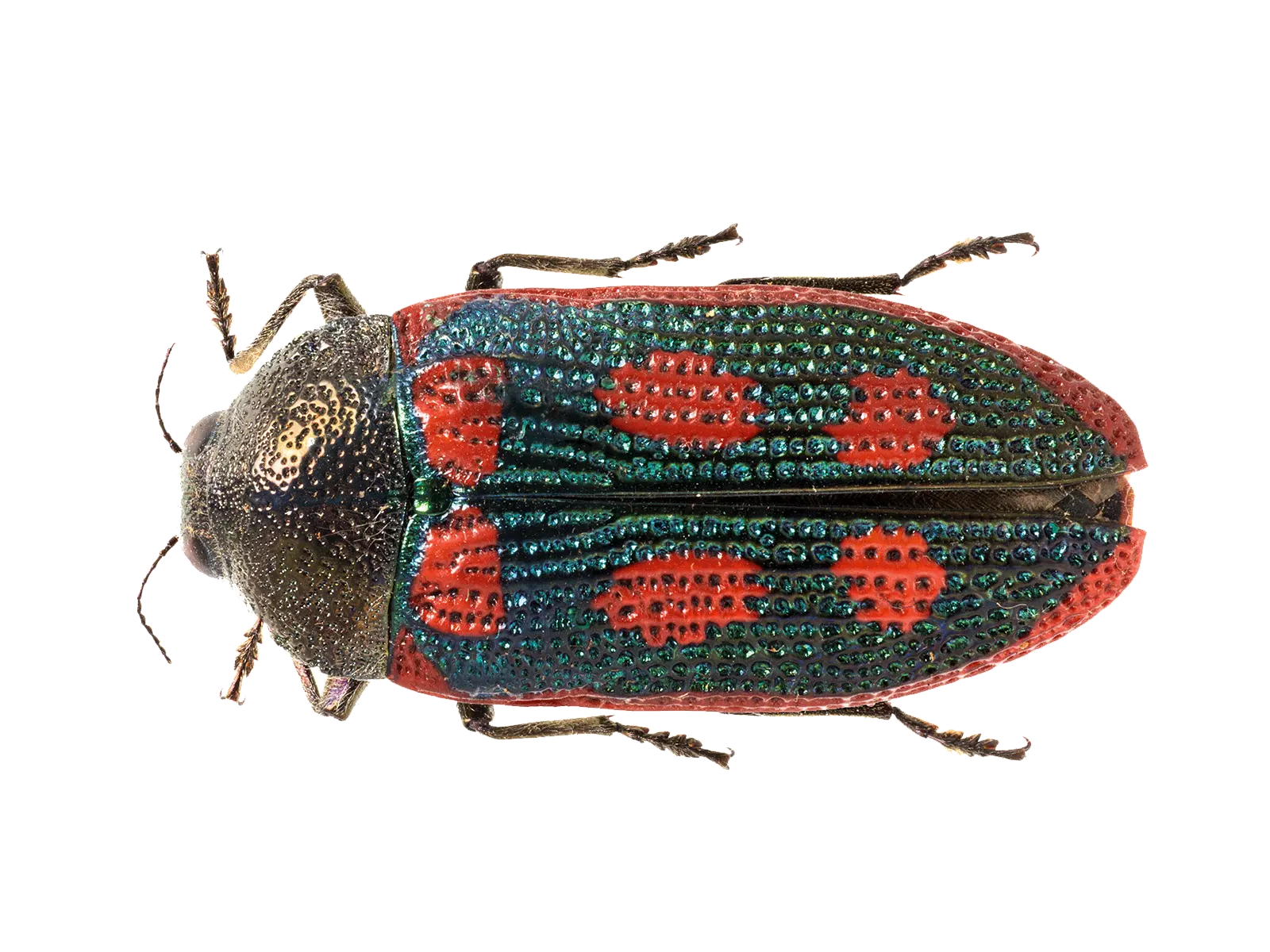

Red spotted jewel beetle

Scientific name: Stigmodera cancellata

Distribution: Western Australia

Size: 23 to 35 mm (1 to 1.5 inches) long

This beautiful beetle is endemic to coastal Western Australia, where larvae live in soil and feed on the roots of myrtle shrubs for up to 15 years. Adults emerge with perfect timing to coincide with the wildflower season: October to November. Females are significantly larger than the males.

The species’ hardened fore wings, or elytra, are greenish or bluish with six irregular red spots and red lateral margins; these protective sheaths are coarsely punctured, giving the beetle a shimmery, bespeckled appearance. S. cancellata’s forebody is green, coppery or blackish.

Huertas likens beetles’ “strong bodies” to armored tanks. Still, she says, a set of delicate wings beneath these insects’ robust wings enables them to fly as efficiently as any other bug species.

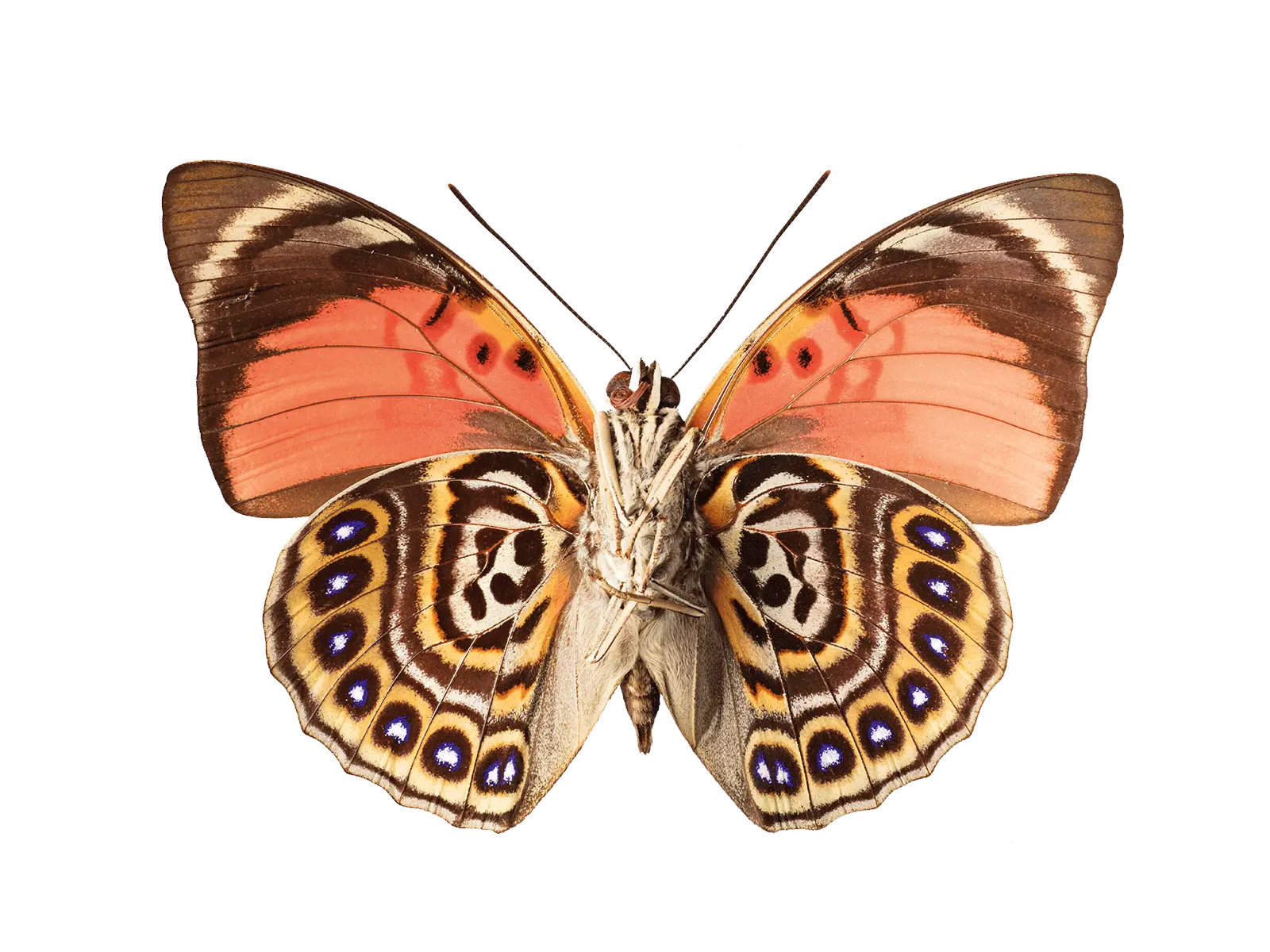

Claudina butterfly

Scientific name: Agrias claudina

Distribution: Tropical South America

Size: 80 mm (3.25 inch) wingspan

The Claudina butterfly entranced British explorer and scientist Henry Walter Bates when he encountered it in the Brazilian Amazon during the 1850s.

This rainforest butterfly has vivid crimson patches on its upper wings, but its underwings are arguably even more spectacular. It does, however, have some unsavory feeding habits—namely, sucking up nutrients from rotting flesh and fruit.

The Claudina butterfly’s underwings are intricately patterned. Its hind wing boasts yellow tufts called the androconia. These special scales, found on many male members of the insect order Lepidoptera, diffuse pheromenes involved in courtship.

“The visible bright colouration in the wings of many butterflies is essential for long-distance communication and it has evolved through advantage to males,” says Huertas. “In some cases, strong coloration is used by some species of butterflies to defer predators. The perception of the colors varies so much between species that it may offer an explanation for the different range of behaviors among them.”

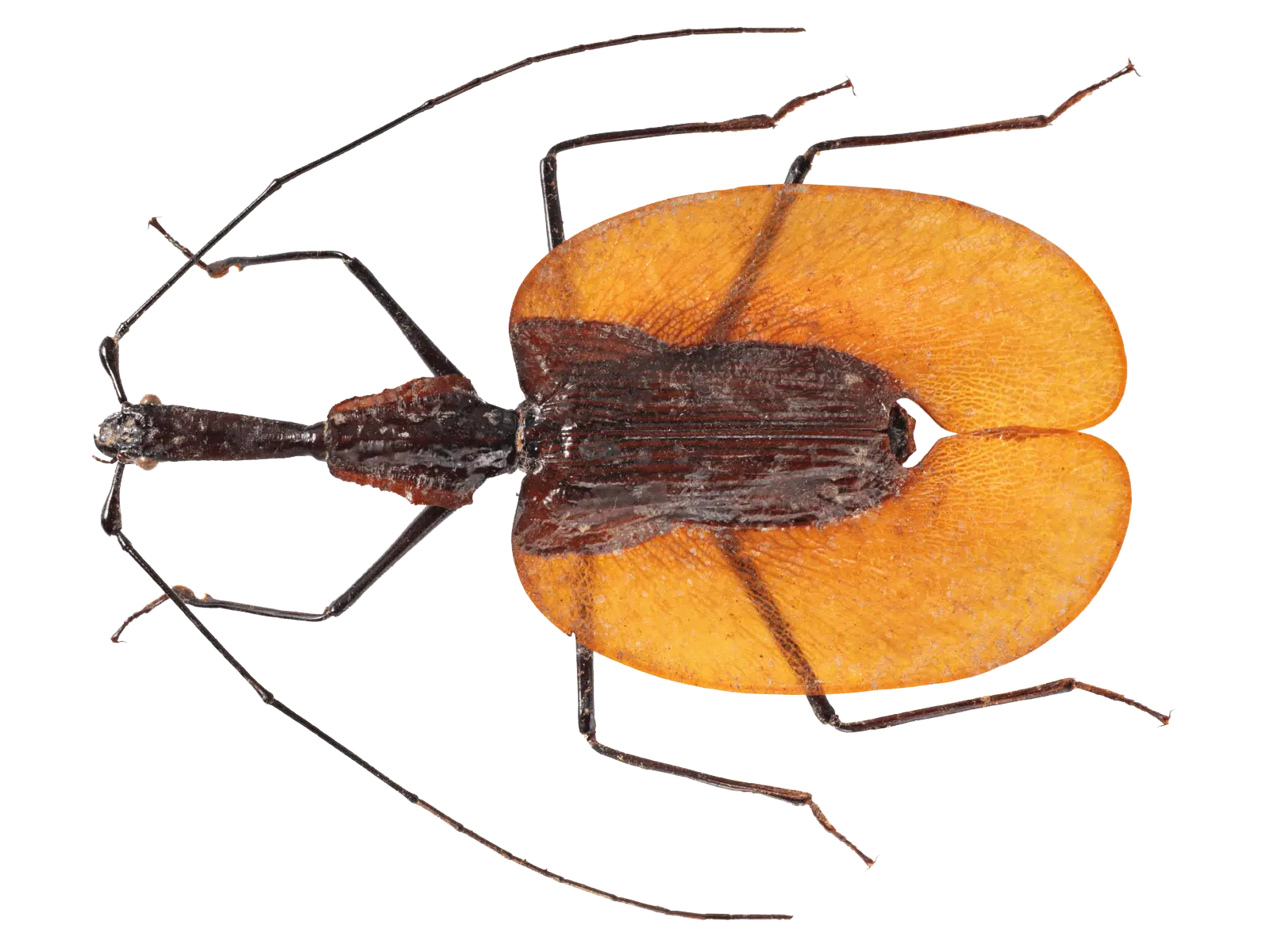

Violin beetle

Scientific name: Mormolyce phyllodes

Distribution: Indo-Malaya

Size: 60 to 100 mm (2.5 to 4 inches) long

This is perhaps the most unusual beetle in the hugely diverse Carabidae family of ground beetles. The shape of its body has been compared to a guitar or violin, and if viewed side on, appears to be completely flat.

M. phyllodes is perfectly suited for life under the loose bark of dead trees or in soil cracks. If disturbed, it will emit a spray of liquid from the tip of its abdomen. The fluid has a strong scent, resembling a mixture of nitric acid and ammonia, and causes a burning sensation if sprayed into the eyes.

Green milkweed grasshopper

Scientific name: Phymateus viridipes

Distribution: Southern Africa

Size: 70 mm (2.75 inches) long

This large African grasshopper secretes a noxious fluid from the thorax when alarmed. The fluid is derived from the poisonous milkweed plants upon which it feeds as an immature nymph or adult. The colored hind wings, which are normally hidden when the grasshopper is at rest, can also be flashed to deter potential predators.

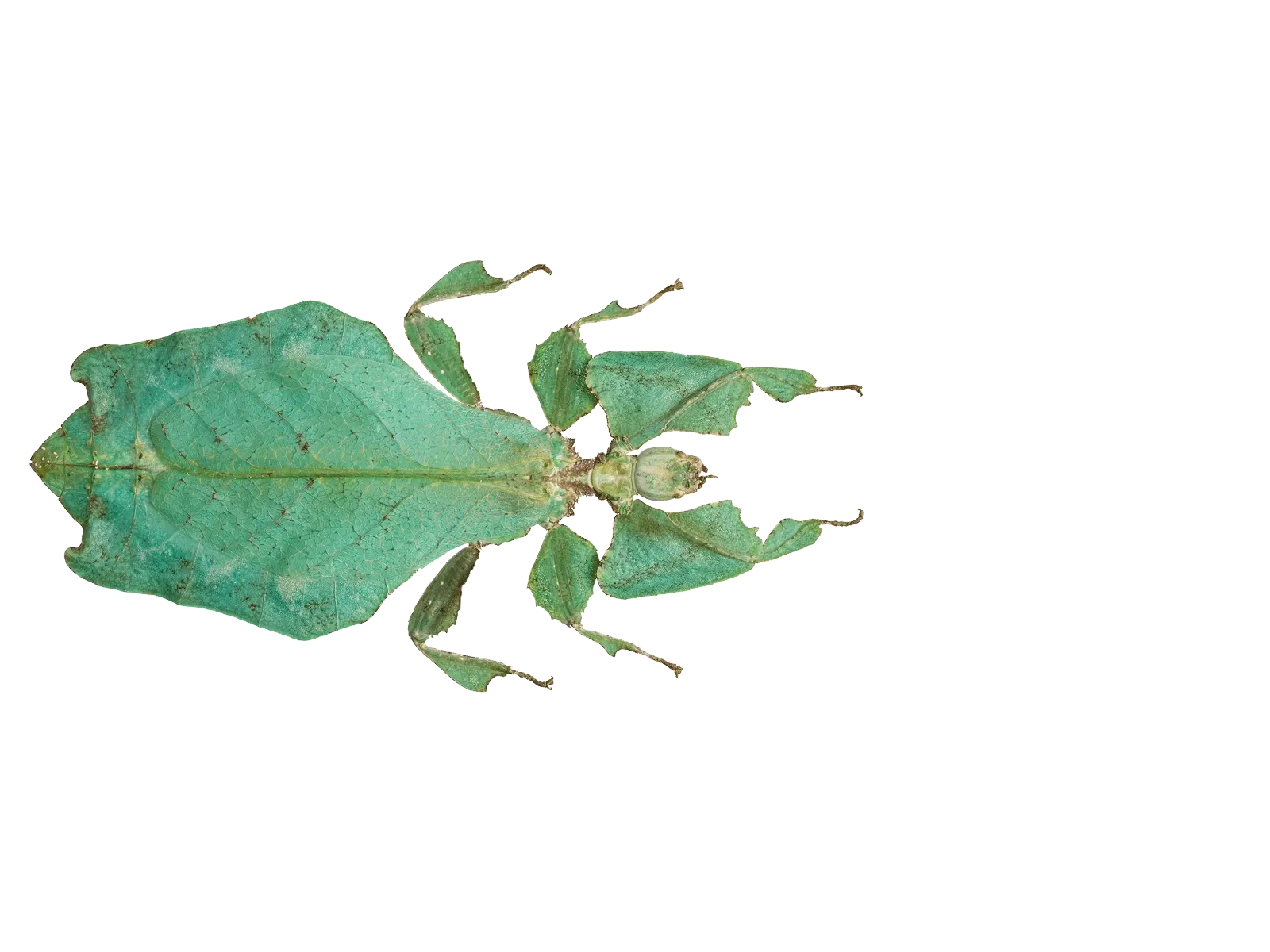

Gray’s leaf insect

Scientific name: Phyllium bioculatum

Distribution: Southeast Asia and Indo-Malaya

Size: 50 to 100 mm (2 to 4 inches) long

Leaf insects are stick insects that have evolved extremely flattened, irregularly shaped bodies, wings and legs. The species derives its name from females’ large, leathery forewings veins, which closely resemble the veins of leaves, affording them superb camouflage abilities. Adult male leaf insects have transparent wings and conspicuous spots on their abdomen—hence their scientific name, which translates to “two-spotted.”

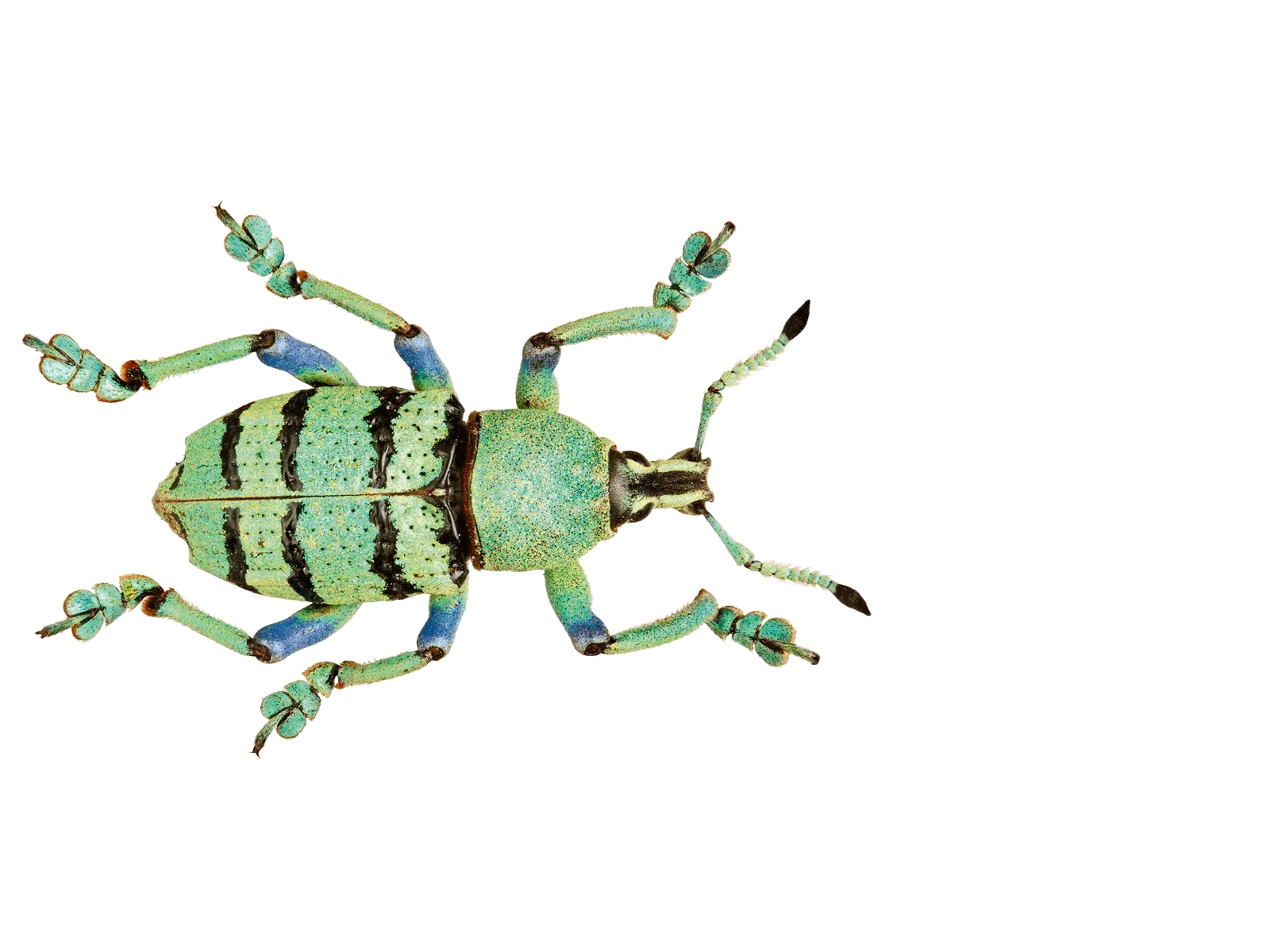

Papuan green weevil

Scientific name: Eupholus schoenherrii

Distribution: New Guinea

Size: 21 to 34 mm (0.75 to 1.25 inches) long

Beetles of the genus Eupholus are rightly considered the most beautiful weevils. Though brightly colored, their coloration is in fact a form of camouflage, combining the tropical blue sky, lush green of vegetation and darkness of tropical rainforests. This particular species is fairly common in northern New Guinea, where it inhabits both primary forests and local gardens.

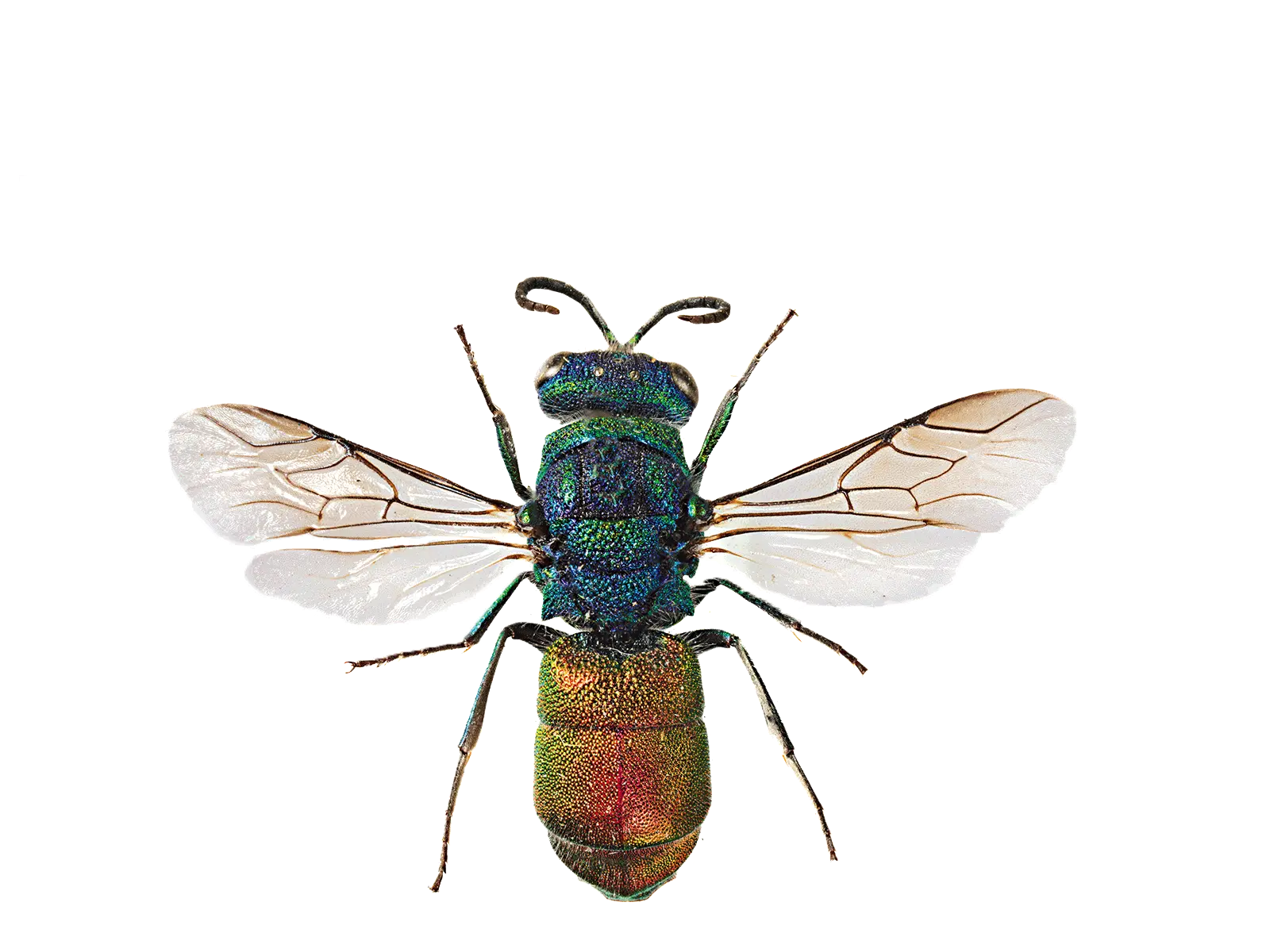

Cuckoo wasp

Scientific name: Chrysis ruddii

Distribution: Throughout Europe and western Asia

Size: 7 to 10 mm (0.25 to 0.5 inches) long

Cuckoo wasps live up to their name by laying their eggs in the nests of bees and wasps. Chrysis ruddii specifically specializes in the clay nests of potter wasps. The young cuckoo wasp eats the nest’s rightful occupant and its food store. When attacked by the bees or wasps they are trying to usurp, cuckoo wasps can roll up into a heavily armored, jewel-like ball.

Metallic tachinid fly

Scientific name: Rhachoepalpus metallicus

Distribution: Tropical South America

Size: 12 to 15 mm (0.5 to 0.75 inches) long

As its scientific name suggests, this fly has a striking, metallic blue sheen. Its abdomen is clothed in long, stout, erect bristles. Metallic coloration is uncommon in this family of flies, but several metallic species from different regions of the world exist. R. metallicus is found in the High Andes of tropical South America, where the larvae probably develop as internal parasites of caterpillars or beetle larvae.

Brush jewel beetle

Scientific name: Julodis cirrosa

Distribution: Southern Africa

Size: 25 to 27 mm (approximately 1 inch) long

This metallic, blue-green jewel beetle has a cylindrical body with a surface coarsely punctured and covered with tufts of long, waxy, whitish, yellow or orange hairs. Larvae tunnel in the stems and roots of various shrubs. Adult beetles are short-lived and active during the heat of the day. They feed on water-rich foliage and flowers.

Wax tailed bug

Scientific name: Alaruasa violacea

Distribution: Mexico and Central America

Size: 85 mm (3.25 inches) long

The wax tailed bug is a member of the Fulgoridae family. Some species of fulgorid nymphs produce waxy secretions from special glands on the abdomen and other parts of the body. Adult females of many species also produce wax, which may be used to protect eggs. Waxy projections from the abdomen are especially developed in this beautiful species from the rainforests of Central America. Adults and nymphs feed on tree sap.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(308x180:309x181)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/2b/872b795f-e647-42a2-bd83-7e7e57a3e2f4/bugs_mobile.jpg)

:focal(1114x333:1115x334)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/27/7427ff38-72fe-438d-811e-37f45832f05c/bugs2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)