World’s Oldest Scorpions May Have Moved From Sea to Land 437 Million Years Ago

A pair of pristinely preserved fossils suggest scorpions have looked mostly the same since they first crawled onto land

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/e8/3ee80ed3-0ff6-49f1-b4f6-c2690d633d5c/hero1.jpg)

Half a billion years ago, the continents were quiet. Earth’s animals—represented largely by shelled mollusks, armored arthropods, and a smattering of wriggly, jawless fish—breathed with gills, not lungs, and hunted their prey at sea.

But sometime, possibly during the Silurian (the geologic period spanning 443 million to 416 million years ago) an intrepid creature, likely equipped with sturdy limbs and a set of gas-cycling tubes that could leech oxygen from air, decided to crawl ashore. In habitually venturing out of the ocean, this animal paved a habitat-hopping path for countless lineages of land-dwellers to come—including the one that eventually led to us.

The identity of this pioneering terrestrial trekker has long perplexed paleontologists. Over the years, several candidates have come forth, all known only by their fossilized remains. Two of the most promising possibilities include many-legged millipedes, eager to snack on the predecessors of today’s plants, and stinger-tipped scorpions—one of the world’s oldest arachnids, the group that also includes spiders. But when and how these arthropods first made that crucial transition from water to land remains an unsolved puzzle.

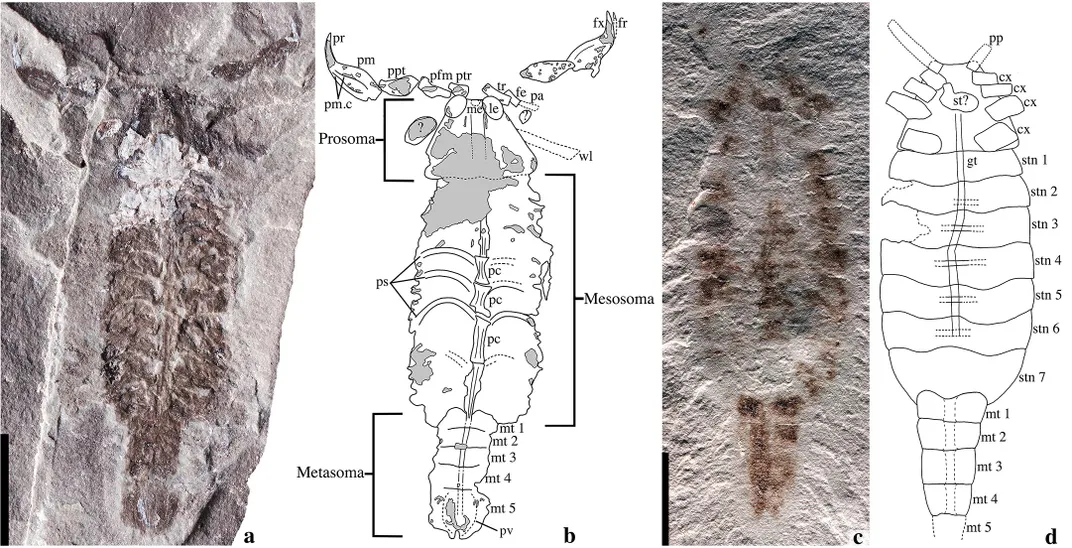

Now, new research is pushing the scorpion timeline further back than ever before and may help pinpoint the traits that helped these pint-sized predators make a living on land. Today in Scientific Reports, paleontologists announce the discovery of the oldest known scorpions to date: a pristinely preserved pair of 437-million-year-old fossils, complete with what seem to be venom-packed tails.

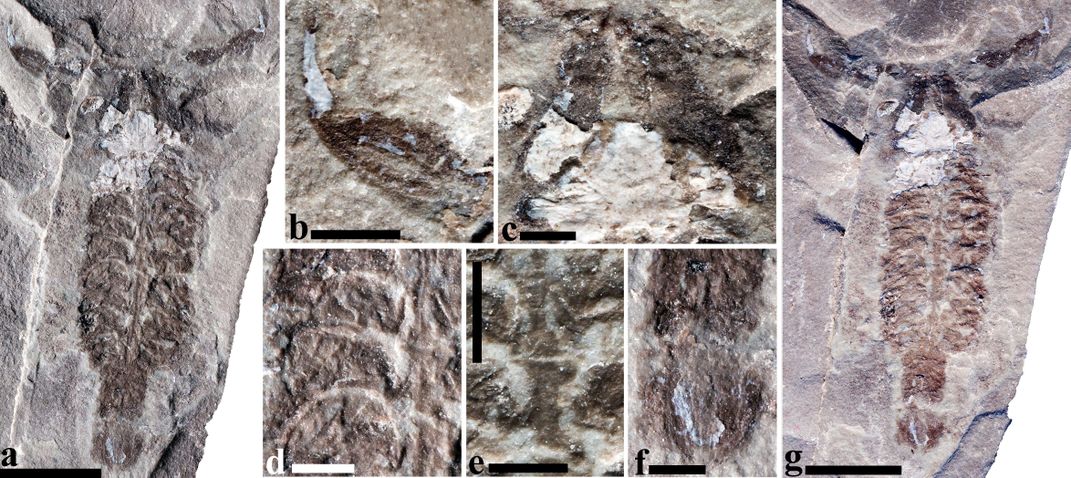

The dangerous-looking duo, newly christened Parioscorpio venator, bear a remarkable resemblance to modern species, showing scorpions hit upon a successful survival strategy early in their evolution, says study author Andrew Wendruff, a paleontologist at Otterbein University. Though Parioscorpio may have spent some of their time at sea, bits of their anatomy, including internal structures used for breathing and digesting food, hint that these ancient animals were capable of scuttling ashore—perhaps, even, to hunt the few creatures that preceded them on land.

Together with other, younger fossils from the same geologic period, the ancient arachnids suggest that scorpions have looked and acted in much the same way ever since they first appeared on Earth.

“It’s always exciting to see a new ‘oldest,’” says Danita Brandt, an arthropod paleontologist at Michigan State University who wasn’t involved in the study. “This one is particularly exciting because it’s an organism living at this very interesting transition from water to land.”

First buried in the sediments of what’s now Wisconsin, a region that contained an extensive reef system during the early Silurian, the Parioscorpio pair spent the next 437 million years encased in rock. Revealed alongside a spectacular trove of other fossils in the 1980s, the specimens then disappeared into a drawer at the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum, where Wendruff would happen upon them some three decades later.

After wearily sifting through troves of trilobites—early marine arthropods that dominate many excavation sites—Wendruff, then a graduate student, was astounded to see “these tiny little things that looked like [inch-long] scorpions,” he recalls. “And that’s what they were.”

Actually convincing himself of his find, however, was a long process. “There were a lot of organisms [from the site] that were marine … but arachnids live on land,” he says. “I kind of didn’t expect it, and I kind of didn’t believe it.” (Six-foot-long marine “sea scorpions” skulked the ancient oceans 467 million years ago, but they were not true scorpions of the land-based lineage that survives today.)

Early scorpions could blur the line between sea- and land-dwellers. Something had to crawl out of the water first, perhaps adopting an amphibian-like lifestyle. Parioscorpio’s physique, a mashup of marine and terrestrial traits, hints it was a good candidate for this double life.

The heads of more recent scorpion species are adorned with multiple rows of beady, pinprick eyes. But Parioscorpio saw the world through bulbous, front-facing compound eyes, similar to the ones still found on today’s insects and crustaceans, as well as its ocean-based ancestors.

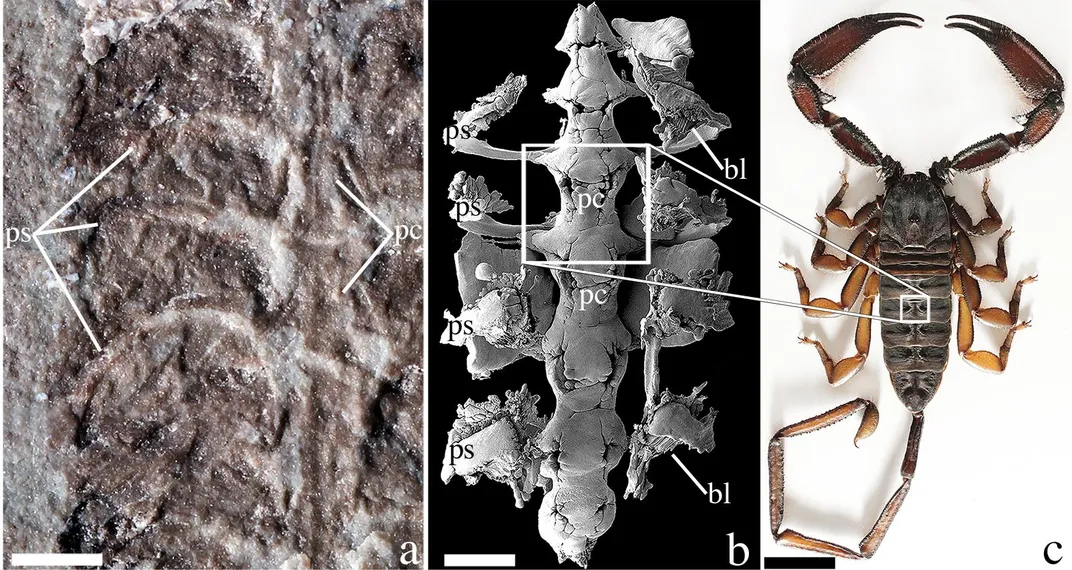

Most of Parioscorpio’s other body parts, however, looked more contemporary. Like the scorpions that plague us today, this ancient animal boasted clawed pincers and a tail that likely tapered into a venomous stinger (though the actual tip, if it existed, has been lost to time). Even its insides were a match: The fossils were so exquisitely entombed that Wendruff could still see the delicate outlines of a simple tube-like gut and a series of hourglass-shaped structures that might have housed their hearts—all of which resembled the innards of modern land-dwelling scorpions.

“The amazing preservation of the internal anatomy … reiterates how the [scorpion] ground plan has stayed the same, not just on the outside, but the inside, too,” says Lorenzo Prendini, a scorpion evolution expert at the American Museum of Natural History who helped uncover another batch of Silurian fossils from this lineage, but wasn’t involved in the new study. “It’s an ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ mentality.”

But Brandt, Prendini and Wendruff are all hesitant to dub Parioscorpio a pure landlubber like the more recent members of its lineage. While the fossils’ respiratory and circulatory systems hint that these scorpions were probably capable of breathing air, that doesn’t mean they actually did—part-time, full-time or otherwise. “There isn’t anything that unambiguously tells you whether they were fully aquatic, terrestrial or amphibious,” Prendini says. Horseshoe crabs, for instance, favor the salty ocean, but are known to make occasional forays onto land, where they can remain for up to four days.

To definitively categorize Parioscorpio, researchers would need to find a fossil with either water-filtering gills—the hallmark of a marine lifestyle—or air-cycling lungs like today’s scorpions have. Unfortunately, Wendruff says, the two breathing structures tend to look a lot alike, especially after millennia underground, and he and his colleagues couldn’t identify either in the specimens.

But even if Parioscorpio wasn’t yet living on land, it was equipped for terrestrial life—putting it, perhaps, on the evolutionary cusp of the major marine-terrestrial transition. Over the years, plenty of other animals have made a similar hop ashore, Brandt points out. To figure out more about how that happened, “maybe it’s time to put them all together,” she says. “What do all these things crawling out of the water have in common?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)