You Say Tyrannosaurus, I Say Tarbosaurus

Was the million-dollar dinosaur a species of Tyrannosaurus, or was it a different sort of dinosaur?

The skull of a mounted Tarbosaurus. Photo by Jordi Payà, from Wikipedia.

Last Friday, the United States government captured a tyrannosaur. The scene was more Law & Order than Jurassic Park. The million-dollar Tarbosaurus skeleton was seized in an ongoing legal dispute about the origins of the dinosaur and how it was imported to the United States. To date, the evidence suggests that the giant Cretaceous predator was illegally collected from Mongolia (a country with strict heritage laws), smuggled to England and then imported to the United States under false pretenses, all before a private buyer bid more than a million dollars for the skeleton at auction. (For full details on the ongoing controversy, see my previous posts on the story.) Now that the dinosaur has been rescued from the private dinosaur market, I can only hope that the skeleton is swiftly returned to the people of Mongolia.

But there’s one aspect of the dispute that I haven’t said anything about. Heritage Auctions, press releases and news reports have been calling the illicit dinosaur a Tyrannosaurus bataar, while I have been referring to the dinosaur as Tarbosaurus. Depending on who you ask, either name might be correct. Embedded in this tale of black market fossils is a scientific argument over whether this dinosaur species was a “tyrant lizard” or an “alarming lizard.”

Paleontologist Victoria Arbour recently wrote an excellent summary of this issue on her blog. In general appearance, North America’s Tyrannosaurus rex and Mongolia’s Tarbosaurus bataar were very similar animals. They were both huge tyrannosaurs with short arms and deep skulls. Unless you really know your dinosaurs, it’s easy to confuse the two. But there are a few significant differences between Tyrannosaurus rex and Tarbosaurus bataar.

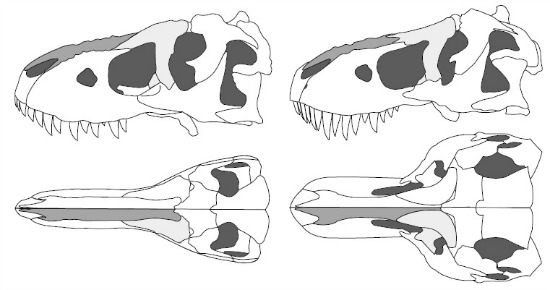

Line drawings of Tarbosaurus (left) and Tyrannosaurus (right) showing the differences in their skulls. Not only is the skull of Tarbosaurus more slender from front to back, but the lacrimal (in light grey) has more of a domed shape. From Hurum and Sabath, 2003.

In 2003, paleontologists Jørn Hurum and Karol Sabath counted the ways the two dinosaur species differed . The most obvious is in the top-down profiles of the tyrannosaur skulls. The skull of Tyrannosaurus rex looks much more heavily built and flares out abruptly at the back, while the skull of Tarbosaurus bataar is narrower and doesn’t have the same degree of expansion at the rear of the skull. A more subtle difference is the shape of the lacrimal bone, which made up the front part of the eye socket and was also part of the dinosaur’s skull ornamentation. In Tyrannosaurus rex, the top portion of the lacrimal has a concave shape, but in Tarbosaurus bataar the same portion of bone is domed. And as Arbour mentioned in her post, the arms of Tarbosaurus bataar are proportionally shorter compared to the rest of the body than in Tyrannosaurus rex—so there are three quick ways to tell the dinosaurs apart.

As Arbour noted, the two dinosaurs definitely belong to different species. As it stands now, the two appear to be each other’s closest relatives. The question is whether they should be two species in the same genus—Tyrannosaurus, which was established first and has priority—or whether each species belongs in its own genus. That decision is influenced as much by a paleontologist’s view of how prehistoric animals should be lumped or split into different taxa as anything else. Some prefer to call the Mongolian form Tyrannosaurus bataar, and others view the tyrannosaur as a very different animal rightly called Tarbosaurus bataar. As you might guess, my vote is for Tarbosaurus.

Like Arbour, I suspect that Heritage Auctions advertised the dinosaur as a Tyrannosaurus to get more attention. Tyrannosaurus is the essence of prehistoric ferocity, and putting a Tyrannosaurus up for sale—rather than a Tarbosaurus—will undoubtedly gain more attention every time. In fact, we know that celebrity has a lot to do with why the legal dispute over the auctioned specimen erupted in the first place. There were other Mongolian dinosaur specimens for sale on auction day, such as a rare ankylosaur skull, but almost no one paid any attention to these specimens. The nearly complete Tarbosaurus was a vacuum for media attention, and it was the most powerful symbol of the rampant fossil smuggling problem. But this isn’t necessarily bad. Perhaps, in time, one outcome of this high-profile case will be to keep other, less charismatic dinosaurs from winding up in the homes of affluent private collectors.

Reference:

Hurum, J.H. and Sabath, K. 2003. Giant theropod dinosaurs from Asia and North America: Skulls of Tarbosaurus bataar and Tyrannosaurus rex compared. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48 (2): 161–190.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)