Your Skin’s Microbial Inhabitants Might Stick Around, Even If You Wash

This tiny ecosystem is surprisingly stable from months to years, study reveals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/c8/52c8ffe6-52fa-4bb9-82d1-8bca4b549dcb/istock_000074142137_medium.jpg)

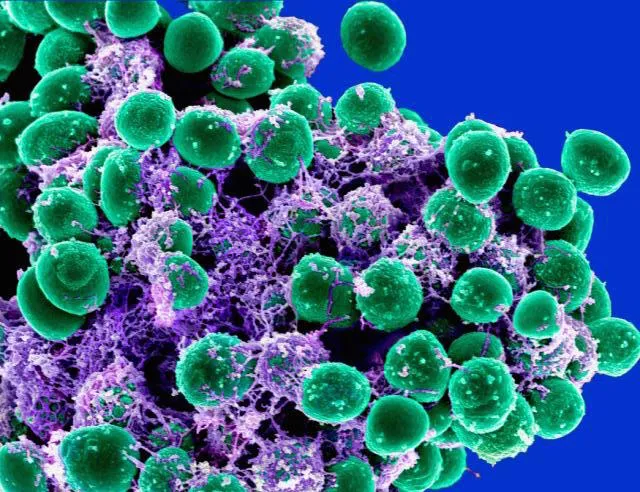

Everyone has cooties—a minute menagerie of bacteria, viruses and fungi that lurk in the microscopic cracks and crevices of your skin.

But before you go running to the sink, know that many of these microbes are beneficial. And, according to new research, this tiny ecosystem, known as the skin microbiome, remains surprisingly stable over time despite regular washing.

The study, published today in Cell, is among a host of recent work attempting to sort through the complexities of this microbial milieu. Though many denizens of the skin are beneficial, some are not. So scientists are trying to better understand this ecosystem in the search for cures for diseases such as psoriasis and eczema.

This puzzle is a tough one to solve because the skin’s microbial residents are impressively diverse. The critters nestled in your armpit can be a world apart from those settled inches away on your forearm—as different as the creatures of a rainforest are to those of a dessert.

These communities can also greatly vary from person to person. What's more, daily living means coming into contact with a host of objects covered in microorganisms, from dogs to doorknobs, and each touch could allow microbe exchange.

To help sort out the complex picture of the skin microbiome, researchers from the National Institutes of Health collected samples from 12 healthy individuals at 17 spots on their bodies. The participants then returned one to two years later for a second sampling, and a third about a month after that, helping scientists understand how the composition of microbes might change over both the short and long term.

The researchers examined the diversity of microbes present at the subspecies level with a technique called shotgun metagenomic sequencing, which allowed them to identify various strains of microorganisms that may differ by only tiny genetic variations.

The skin microbiome “is surprisingly stable,” says one of the study’s leaders, Heidi Kong of the National Cancer Institute. This means that individuals tended to retain their own microbial menagerie, rather than picking up the countless foreign intruders they encountered.

“But...it depends on where you were on the body,” Kong notes. Oily sites, such as the back, were the most stable of the group. Meanwhile, the feet and other moist sites were the least.

The stability of oily sites makes sense if you consider their food source, says Gilberto Flores, a microbial ecologist at California State University Northridge who was not involved in the study. For many microbes, the skin’s oils are akin to an all-you-can-eat buffet.

“If there's a constant supply of food for [the microbes], then the communities will probably remain more stable,” he says.

Malassezia fungi, a microbe commonly found on human skin, is one such example. It can only be grown in the lab with the addition of oil, says Kong. So it is likely using the oils of the skin to survive and thrive.

Even so, the stability of dry locations on the body, like the palms, was relatively high. Considering the number of times most people wash their hands in a day, how can this be?

The first thing to keep in mind is scale, says Flores. Skin microbes aren’t just hanging on like a piece of rice stuck to the back of your hand. “We see [the skin] as a flat surface, but it's really a three-dimensional structure at that scale,” he says.

The stability of microbes on the hands also highlights that there are physiologic characteristics of the skin that could help shape these microbial communities, says Kong. These tiny inhabitants may also be producing compounds that prevent others from taking up residence, she says.

In addition, the researchers found that, similar to previous studies, stability in all spots is specific to an individual. Some people’s microbial communities shift more than others. Overall, the results suggest that any hypothetical skin treatments that alter the microbial cohort must be personalized to each patient.

The results are particularly notable because information about which subspecies inhabit the skin microbiome remains scarce. Yet recent studies have suggested that the subtle differences that delineate microbial strains can completely change how the host reacts to these inhabitants.

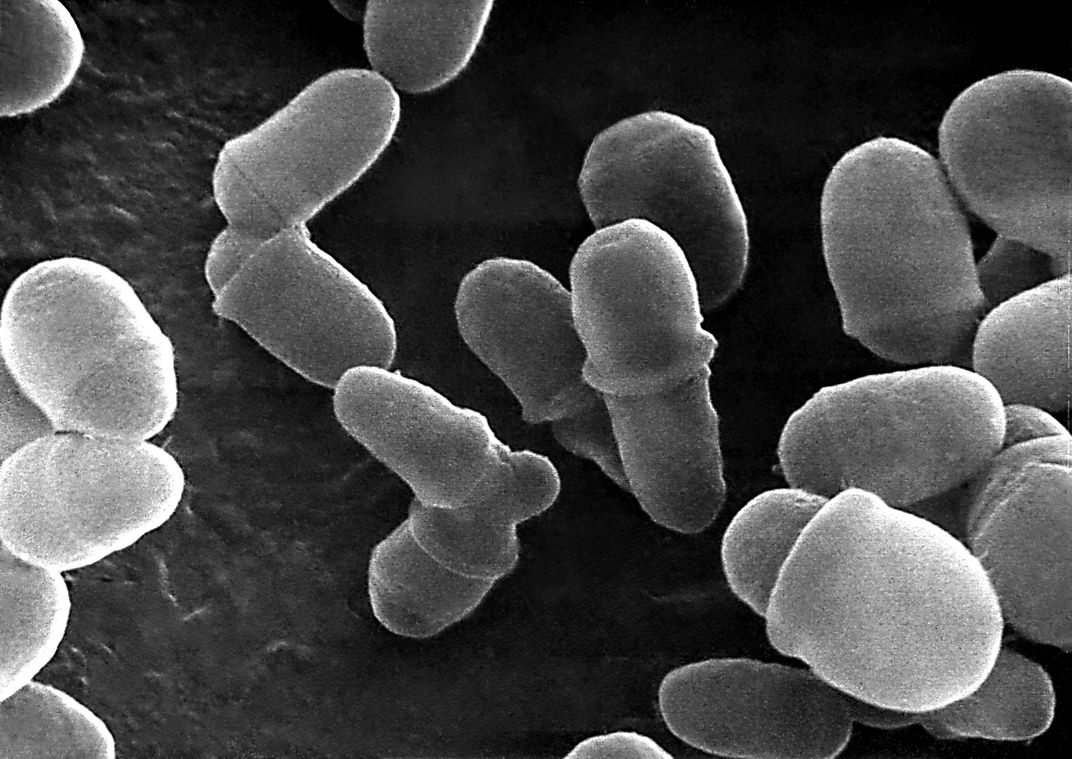

Take, for example Propionibacterium acnes. Some strains of this bacterium are associated with painful acne flares, yet others are inhabitants of clear, healthy skin. Kong and her colleagues found that each individual's cohort of P. acnes strains remained remarkably stable over time, but their composition vastly differed between people. Without the subspecies information, these differences would have been overlooked.

Though the sample size of this study is modest, it provides a foundation for continued mapping of the skin’s complexities, says Kong. More research is also necessary to tease out the relationship between microbes and disease, but as technologies advance by leaps and bounds, the picture of the body’s many microbial menageries is slowly coming into focus.

“It’s an exciting time to be a microbiologist,” says Flores.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)