A 1,000-Square-Foot Mosaic of Ida B. Wells Welcomes Visitors to D.C.’s Union Station

The artwork, installed in honor of the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, celebrates the pioneering civil rights leader and journalist

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/1c/ae1c913c-128e-4485-b3c0-9630d09263f9/img_7777-2-new-scaled215-1500x1072.jpg)

In September 1883, a conductor on a train bound from Memphis to Woodstock, Tennessee, ordered a young Ida B. Wells to leave her first-class seat in the rear coach, which he claimed was reserved for white passengers, and move to a section most often frequented by smokers and drunks. She fought back, even biting the conductor, but was eventually forcibly removed by a group of three men.

The following year, Wells sued the railroad—and won a $500 settlement (around $13,000 today). But Tennessee’s Supreme Court later reversed the lower court’s decision, ruling in favor of the segregationist company.

This experience marked a turning point in the African American writer’s life, sparking her decades-long career as a civil rights, anti-lynching and suffrage activist, according to the National Park Service. Now, almost 140 years after the incident, a 1,000-square-foot mosaic of Wells adorns the floor of Union Station. Fittingly, notes Black Entertainment Television, the Washington, D.C. station is one of the country’s busiest transportation hubs.

The Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission (WSCC) sponsored the installation, titled Our Story: Portraits of Change, in honor of the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. Officially ratified on August 18, 1920, the legislation granted many American women—but not all—the right to vote.

Per a statement, the enormous portrait—created by British artist Helen Marshall and produced by Christina Korp of Purpose Entertainment—will be on view through August 28.

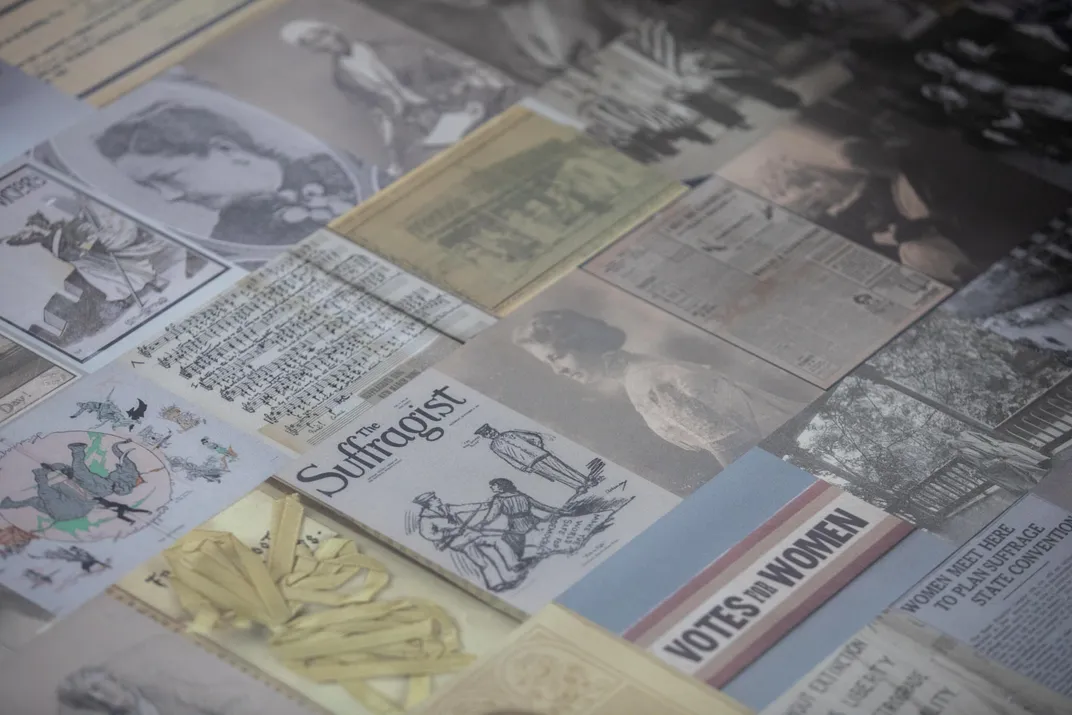

As Rosa Cartagena reports for Washingtonian, the likeness is composed of some 5,000 smaller images that document American women’s struggle for suffrage. Those unable to visit Union Station in person can explore an interactive version of the mosaic online.

“What we are able to do with this art installation is that we can show the depths of this movement,” Anna Laymon, executive director of WSCC, tells CNN’s Amanda Jackson. “It wasn’t just one woman who fought for the right to vote … [I]t was thousands.”

As a journalist, publisher and activist, Wells was an outspoken critic of racial injustice. She investigated and wrote in-depth reports on lynching in America, as well as owned and edited several newspapers, wrote Becky Little for History.com in 2018. This year, the Pulitzer Prize posthumously honored Wells for her “outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.”

In addition to enduring racial discrimination in broader society, Wells faced prejudice from within the suffrage movement. When organizers told her and other black suffragists to march in the back of the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade, she refused, instead marching alongside white suffragists in the Illinois delegation.

“We need to see [Wells’] portrait, and African American women need to be a lot more visible,” Marshall tells Mikaela Lefrak of DCist. “She was fighting for the same causes that women are now.”

According to the statement, Union Station served as the starting point for the so-called “Prison Special” tour. In early 1919, Lucy Burns and other suffragists who’d been imprisoned for fighting for their right to vote rode a train dubbed the “Democracy Limited” across the United States. Departing from D.C., the 26 women traveled to cities around the country, including New Orleans, Los Angeles and Denver.

As Brianna Nuñez-Franklin writes in a National Park Service series on the campaign, participants leveraged their status as wealthy, well-connected white women to shock audiences with tales from prison. White leaders’ emphasis on “respectability politics” often led them to exclude black and Native American women from the movement.

Other suffragists included in the mosaic include influential black educator Mary McLeod Bethune; black abolitionist, poet and early feminist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper; Burns, who founded the National Women’s Party with fellow white suffragist Alice Paul; and Susan B. Anthony, founder of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

“It’s a beautiful thing to see the level of acknowledgment Ida B. Wells is getting in just these few short years,” says Nikole Hannah-Jones, a New York Times magazine journalist and the co-founder of the Ida B. Wells Society for investigative reporting, on Twitter. “This is wonderful.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/34/cb342dcb-7dda-4bde-874a-577bd9d02308/gettyimages-1268275424.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/04/54045149-4d0b-4158-84ad-b573d9340535/amanda_rhoades_-_5d4a5072.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/9d/3c9d32c6-ebd8-46fd-823a-4ba967863b0e/gettyimages-515306388.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/ac/42ac2d7a-a979-4860-b0f0-535b7365e670/screen_shot_2020-08-24_at_125627_pm.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/57/b657ac46-53d2-4250-82df-84c3b0d6b3c1/1024px-ida_b_wells_circa_1895_by_cihak_and_zima.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)