In the 1930s, This Natural History Curator Discovered a Living Fossil–Well, Sort of

Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer was convinced she’d found something special in a pile of fish, but it took some time for her discovery to be recognized

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/cf/26cf7a8c-c73e-4a39-a7d6-1d375d5e5a88/latimer-2.jpg)

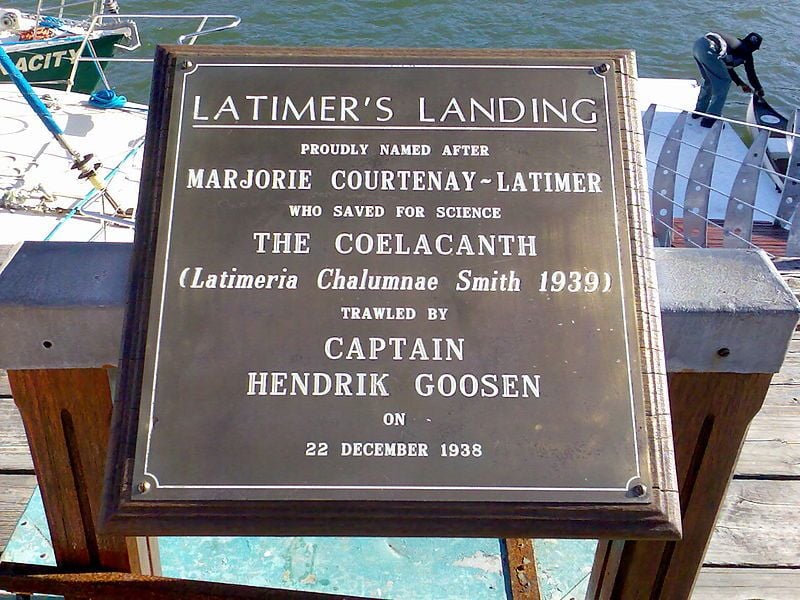

It was a pre-Christmas miracle: on this day in 1938, when an observant curator spotted something seemingly impossible in a waste pile of fish.

Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, a museum curator in East London, South Africa, was paying a visit to the docks as part of her regular duties. One of her jobs, writes Anthony Smith for The Guardian, was to “inspect any catches thought by local fishermen to be out of the ordinary.” In the pile of fish, she spotted a fin. Later, writes Smith, Courtenay-Latimer recalled that “I picked away at a layer of slime to reveal the most beautiful fish I had ever seen. It was pale mauvy blue, with faint flecks of whitish spots; it had an iridescent silver-blue-green sheen all over. It was covered in hard scales, and it had four limb-like fins and a strange puppy-dog tail."

The natural history curator, whose specialty was birds, had been curious about the natural world since childhood, and her fascination prepared her to make one of the greatest zoological discoveries of the early twentieth century. Courtenay-Latimer didn’t know what the fish was, writes The Telegraph, but she was determined to find out. What followed is a familiar tale of women scientists’ curiosity being disregarded.

First, working with her assistant, she convinced a taxi driver to put the 127-pound dead fish in the back of his cab and take them back to the museum. “Back at the museum, she consulted reference books, but to no avail,” writes Smith. “The chairman of the museum's board was dismissive. ‘It's nothing more than a rock cod,’ he said, and left for his holiday.”

But she was convinced it was something important, and even though she couldn’t figure out what it was, attempted to preserve the fish so it could be examined by an icythologist–first by taking it to the local hospital morgue (they wouldn’t store it) and then by having it taxidermied, sans organs.

Then she called up a museum curator of fishes for coastal South Africa named J.L.B. Smith, but he wasn’t in to take the call. “When he hadn't returned her call by the next day, she wrote to him,” reports Peter Tyson for Nova PBS. She included a rough sketch and described the specimen.

What followed was an increasingly intense correspondence. By January 9, Smith wrote to Courtenay-Latimer saying the fish had caused him “much worry and sleepless nights” and that he was desperate to see it. “I am more than ever convinced on reflection that your fish is a more primitive form than has yet been discovered,” he wrote.

By February, writes Tyson, the researcher couldn’t contain himself. He reached the museum on February 16. “Although I had come prepared, that first sight [of the fish] hit me like a white-hot blast and made me feel shaky and queer, my body tingled," he later wrote. "I stood as if stricken to stone. Yes, there was not a shadow of doubt, scale by scale, bone by bone, fin by fin, it was a true Coelacanth."

Coelacanths were believed to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago. Turns out, they lived and evolved. But in 1938, the discovery of a modern coelacanth was like seeing a fossil come back to life. Today, the two known living species of coelecanth are the only members of the genus Latimeria, named for the curator who discovered the first specimen in a pile of rubbish.