Newberry Library Digitizes Trove of Lakota Drawings

The art is part of a larger digitization project of early American history by the Chicago-based research library

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/20/e62019e9-19f4-4542-aec0-bc414b73dcf9/newberry_sioux_indian_drawings.jpg)

During a rough North Dakota winter some 100 years ago, native people living in Fort Yates created art that captured scenes from their every-day life. Using watercolor and colored pencil, they created vivid depictions of hunting, dancing and community life.

While you wouldn't know it looking at the art, it was made for survival. The corn and potato harvest that summer had failed. The cattle had mysteriously disappeared. According to Chicago’s Newberry Library, the winter of 1913-14 was, in fact, referred to as the "Starving Time" by the Fort Yates' Santee, the Yankton-Yanktonai and the Lakota peoples (collectively called "Sioux Indians" by white settlers) for its particularly brutal conditions.

In this desparate period, an Episcopal missionary fluent in Sioux named Aaron McGaffey Beede had come along and promised small amounts of money, in the form of 50-75 cents, for their drawings.

Now 160 of the works from the collection are available for view in the digitized collection of the independent research library, Claire Voon reports for Hyperallergic.

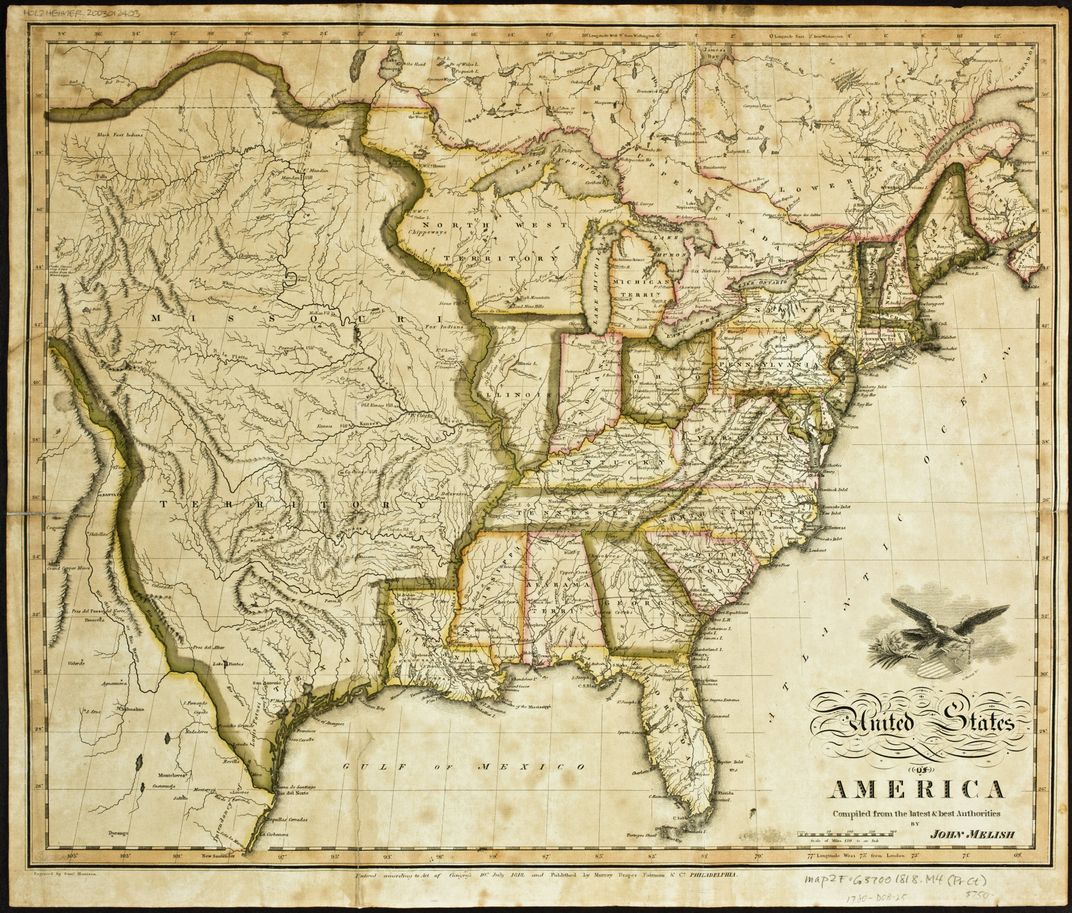

The drawings are part of a larger project providing access to more than 200,000 documents and images offering a peek into early American history and westward expansion. It includes maps, manuscripts, books, pamphlets, photographs and artwork, such as a poster for “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,” according to the Newberry.

Together, the new documents tell a story, among other historical narratives, about Europe’s conception of America, early contact with native peoples, expanding boundaries and the concept of the West.

But the Lakota artwork — 40 of which were created by children — is particularly interesting because, as Voon points out, the works represent an act of survival.

The museum acquired the three boxes of the art in 1922, which was attributed to “Sioux Indians” of Fort Yates, the U.S. military post renamed the Standing Rock Agency in 1874, in the present-day town of Fort Yates in Sioux County North Dakota.

Per the State Historical Society of North Dakota, conditions for natives at Fort Yates ultimately became brutal. "Government interference in all facets of Indian life made the Dakota and Lakota of Standing Rock Agency virtual prisoners on their own land, subject to government policy that sought to crush their cultural ways and distinctiveness as a people."

Beede, who requested the art go in the Newberry's Edward E. Ayer Collection, explained in a letter highlighted by FlashBak of his intent behind commissioning the works. "It is saving pictures, which will be very valuable in future that I want.” He also asked to be paid $100 for the collection.

While his aim was to have native people document their own stories, FlashBak points out that, of course, native people were already doing so on their own in a multitude of ways, such as through waniyetu wówapi chronology (translated into "winter count"), a unique illustrated history of the years through important or unusual events.

Correction, May 4, 2018: An earlier version of this story misspelled the name for reporter Claire Voon. Aaron McGaffey Beede's last name was also spelled Bead, based on a sourcing error.