3-D Scans of the Bust of Nefertiti Are Now Available Online

A German museum released the digital data to artist Cosmo Wenman after a hoax heist and lengthy legal battle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/82/a182796a-544e-44d5-9375-6582188bd7b3/20191111-nefertiti-scan-render-by-cosmo-wenman_003-1024x768.png)

The tale of the Nefertiti bust begins in Egypt in 1345 B.C. and leads to a digital design sharing portal called Thingiverse. As artist and 3-D scanning expert Cosmo Wenman announced earlier this month, Berlin’s Neues Museum has sent him a flash drive containing full-color scans of the famous artifact following a three-year legal battle over the data’s release. Wenman made these scans freely available online on November 13.

Since its discovery by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt in 1912, the ancient bust has traced a contentious path. According to a 2012 report by Time’s Ishaan Tharoor, Egyptian authorities started petitioning Germany for the artifact’s return as soon as they realized its importance. Although Adolf Hitler’s Nazi government appeared poised to return the bust during the 1930s, the dictator soon changed his mind, declaring that he would “never relinquish the head of the queen.” The sculpture spent World War II in a salt mine but was recovered by the Allied forces’ Monuments Men in 1945 and put back on display in Berlin.

Egypt has continued to request the artifact’s return, albeit with little success. In 2011, the country’s Supreme Council of Antiquities sent its petition to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, which runs the museum where the bust is on display.

“The foundation’s position on the return of Nefertiti remains unchanged,” the group’s president, Hermann Parzinger, said in a statement quoted by Reuters at the time. “She is and remains the ambassador of Egypt in Berlin.”

More recently, the debate’s focus has shifted to digitization. Many museums create three-dimensional scans of their artifacts, Wenman writes for Reason, but only some—including the Smithsonian Institution—make those scans available to the public. The Neues Museum in Berlin decided to keep its full-color scan of the Nefertiti bust under lock and key.

But in 2016, a pair of artists revealed the result of an alleged digital heist: Standing alongside a colorless scan of the bust, Berlin-based duo Nora al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles claimed that they had snuck a modified Kinect scanner into the museum and used it to create a digital 3-D model of the artifact, Ocean’s 8-style. Wenman was among the first experts to criticize the artists’ story. The scan was simply too high quality, he said, and too similar to a scan the museum commissioned from a company that posted its work online in 2008.

“In my opinion, it’s highly unlikely that two independent scans of the bust would match so closely,” Wenman wrote in 2016. “It seems even less likely that a scan of a replica would be such a close match. I believe the model that the artists released was in fact derived from the Neues Museum’s own scan.”

He added that based on his experience, people want data, and “When museums refuse to provide it, the public is left in the dark and is open to having bogus or uncertain data foisted upon it.”

After the hoax heist, Wenman launched his own campaign to acquire the museum’s scans. As the artist recounts for Reason, when he submitted a request citing German freedom of information laws that apply to state-funded institutions including the Neues, the museum referred him to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. According to Wenman, the foundation claimed that “directly giving [him] copies of the scan data would threaten its commercial interests.” Instead, the group offered to let him visit the German consulate in Los Angeles, where he is based. There, he was allowed to view the scans under supervision.

“It’s very difficult to find anyone who is able to actually articulate a coherent reason for keeping this kind of data away from the public,” Wenman tells Naomi Rea of artnet News. “I believe their policy is informed by fear of loss of control, fear of the unknown, and, worse, a lack of imagination.”

Wenman pressed the museum on its commercial claims, and after three years of negotiations, the foundation finally gave him a flash drive containing the high-resolution, full color scans. The artist then put this data online.

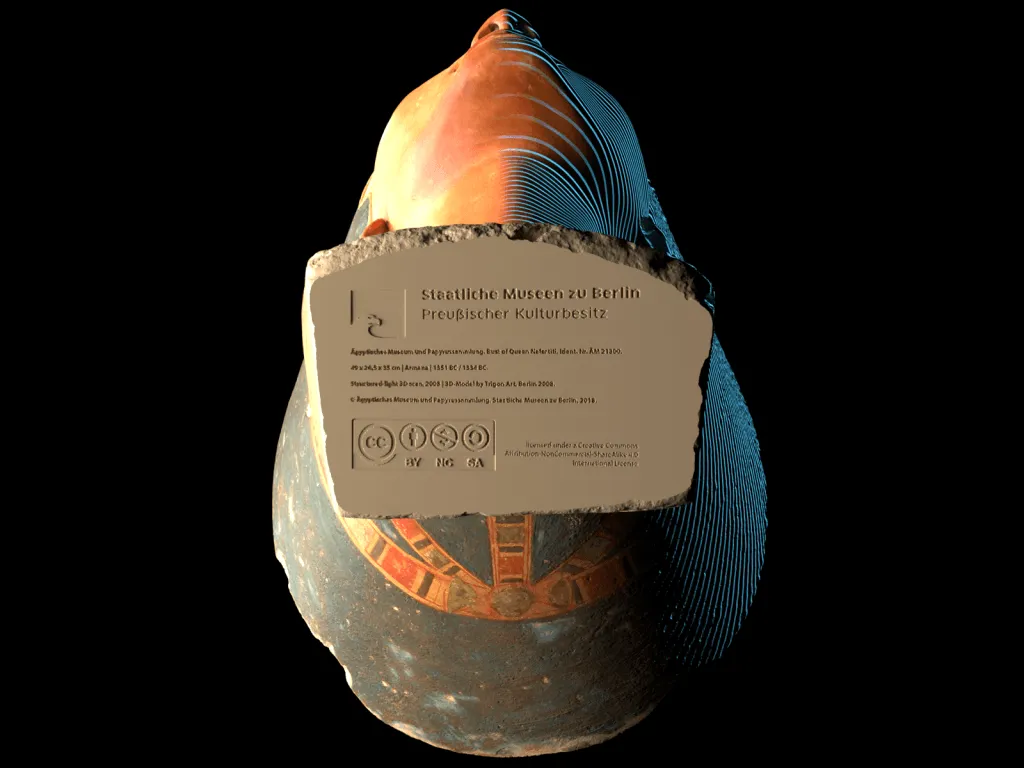

The scan captures every detail that made the bust so iconic, including Nefertiti’s delicate neck, painted headdress, high cheekbones and sharp eyeliner. But it also includes one extra detail—namely, a Creative Commons Attribution copyright notice digitally etched onto the bottom of the sculpture. The license outlines three conditions for use of the scan: The model must be attributed to the museum, it cannot be used for commercial purposes and anything made from it must be available for reuse by others.

The legality of the Neues Museum’s copyright claim remains unclear. Writing for Slate, Michael Weinberg, executive director of the NYU School of Law’s Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy, suggests the notice may have been added to discourage widespread use of the scan, even without the weight of law.

Weinberg explains, “Those rules only matter if the institution imposing them actually has an enforceable copyright. … There is no reason to think that an accurate scan of a physical object in the public domain is protected by copyright in the United States.”