3-D Imaging Reveals Toll of Parthenon Marbles’ Deterioration

A new study of 19th-century plaster casts of the controversial sculptures highlight details lost over the past 200 years

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/3b/e23be06d-e1e1-4d3d-9839-1b1b828c409e/screen_shot_2019-12-11_at_122127_pm.png)

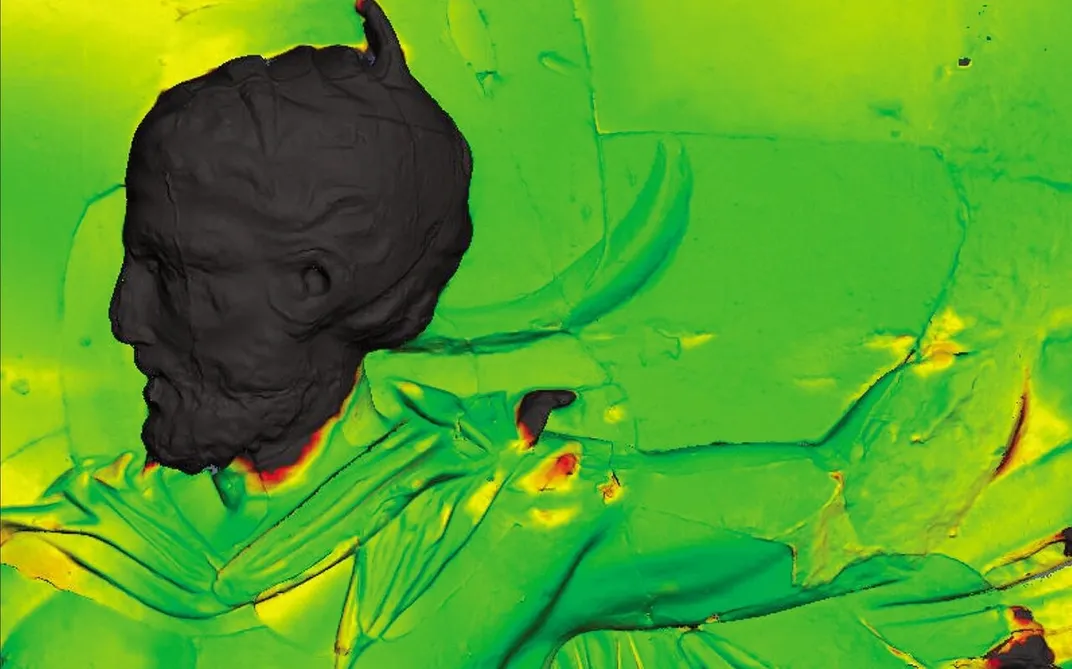

A new analysis of Lord Elgin’s original casts of the Parthenon marbles has revealed details effaced by Victorian vandals—and air pollution—following the classical sculptures’ removal from Greece in the early 19th century.

Published in the journal Antiquity, the survey compared 3-D images of the original plaster casts with later versions made in 1872, spotlighting both the high quality of the centuries-old casts and the extent of damage sustained by the marbles in the 217 years since their arrival in Great Britain.

The casts are just one element of perhaps the art world’s most divisive controversy. In 1802, Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, commissioned the removal of around half of the statues and friezes found in the ruins of the Parthenon in Athens. He transported the works back to his country, and in 1816, sold them to the British government. The next year, the marbles went on view at the British Museum in London, where they have remained ever since.

As Esther Addley reports for the Guardian, study author Emma Payne, a classics and archaeological conservation expert at King’s College London, embarked on the project in order to determine whether the original Elgin casts, as well as the versions made under the supervision of Charles Merlin, British consul to Athens, in 1872, still contained useful information.

Per a press release, Payne hoped to answer two key questions: First, how accurate were the 19th-century casts, and second, do the casts “preserve sculptural features that have since been worn away from the originals—do they now represent a form of time capsule, faithfully reflecting the condition of the sculptures in the early 19th century?”

Payne adds, “Elgin’s casts could be important records of the state of the sculptures in the very early 19th century before modern pollution would hasten their deterioration.”

The archaeologist and classicist used a Breuckmann smartSCAN 3-D device to model the Elgin and Merlin molds. Then, she overlaid the 3-D scans with modern images of the artworks.

Overall, says Payne, the 19th-century casts reproduce the original marbles “more accurately than expected.” Most deviate less than 1.5 millimeters from the sculptures themselves, in addition to preserving details lost over the past two centuries.

The analysis suggests the artworks suffered the most significant damage between the time the Elgin and Merlin casts were made, with Victorian-era looters targeting the valuable marbles. Pieces of the statues appear to have been chipped off, leaving tool marks still visible today. In contrast, damage incurred between the 1870s and the present day was much less severe.

Although the Elgin casts are largely faithful representations, Payne found that the craftsmen tasked with making the molds often sought to “correct” broken sculptures, adding in crude, makeshift versions of missing faces and limbs. The survey found more evidence of this practice than had been previously documented.

Still, Payne tells the Guardian, she is impressed by the quality of the casts.

She adds, “Certainly the results very much emphasize the skill of the casters, and it shows that there is still information that we can potentially learn about the Parthenon sculptures from these 19th-century studies that haven’t really been looked at in detail.”

Next, Payne hopes to examine casts made from artworks uncovered at Delphi and Olympia.

Since Greece gained independence from the Ottoman Empire 200 years ago, the nation has argued that the marbles should be repatriated from Great Britain. The current Greek government has made the works’ return a priority, and the nation even has a museum below the Parthenon waiting to receive the artworks.

The British Museum, on the other hand, contends that the sculptures should stay on British soil, arguing that the Parthenon’s history is enriched by displaying some of the sculptures in the context of global cultural exchange.

Payne has mixed feelings on the controversy.

“While I certainly don’t condone Elgin’s removal of the sculptures, we can be thankful that he also made efforts to create plaster casts,” she tells Sarah Knapton at the Telegraph.

The researcher also agrees that the marbles housed in the British Museum are in better shape than they would be otherwise.

“It is very likely that the pieces of Parthenon sculpture in the British Museum would now be in poorer condition if Elgin had left them on the Acropolis,” she says. “On the whole, they have been safer in the museum than exposed to modern pollution on the Acropolis—this is precisely the reason for which the remainder of the frieze was removed to the Acropolis Museum in the 1990s.”