Tomb Painting Known as Egypt’s ‘Mona Lisa’ May Depict Extinct Goose Species

Only two of the three kinds of birds found in the 4,600-year-old artwork correspond to existing kinds of animals

:focal(1637x1254:1638x1255)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/0b/e20b7425-586a-465a-a532-cc8ff1d02237/gettyimages-122316358.jpg)

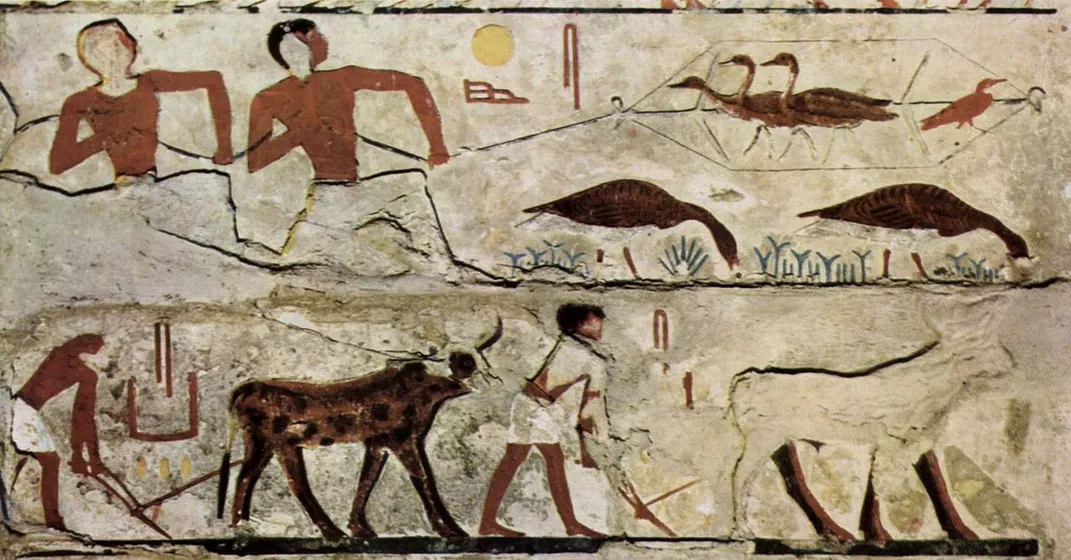

The 4,600-year-old tomb painting Meidum Geese has long been described as Egypt’s Mona Lisa. And, like the Mona Lisa, the artwork is the subject of a mystery—in this case, a zoological one.

As Stuart Layt reports for the Brisbane Times, a new analysis of the artwork suggests that two of the birds depicted don’t look like any goose species known to science. Instead, they may represent a type of goose that is now extinct.

Anthony Romilio, a paleontologist at the University of Queensland in Australia, noticed that the animals somewhat resembled modern red-breasted geese. But they aren’t quite the same—and researchers have no reason to believe that the species, which is most commonly found in Eurasia, ever lived in Egypt.

To investigate exactly which kinds of geese are shown in the artwork, Romilio used what’s known as the Tobias method. Essentially, he tells the Brisbane Times, this process involved comparing the painted birds’ body parts to real-life bird measurements. The resulting analysis, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, found that two species shown in the artwork corresponded to greylag geese and greater white-fronted geese. But two slightly smaller geese with distinctive color patterns had no real-world match.

“From a zoological perspective, the Egyptian artwork is the only documentation of this distinctively patterned goose, which appears now to be globally extinct,” says Romilio in a statement.

While it’s possible that the artist could have simply invented the birds’ specific look, the scientist notes that artwork found at the same site depicts birds and other animals in “extremely realistic” ways. He adds that bones belonging to a bird that had a similar, but not identical, appearance to the ones shown in the painting have been found on the Greek island of Crete.

Per Live Science’s Yasemin Saplakoglu, Meidum Geese—now housed in Cairo’s Museum of Egyptian Antiquities—originally adorned the tomb of Nefermaat, a vizier who served the Pharaoh Snefru, and his wife, Itet. Discovered in what’s known as the Chapel of Itet, it was originally part of a larger tableau that also shows men trapping birds in a net.

Other paintings found in the chapel feature detailed depictions of dogs, cows, leopards, and white antelopes, writes Mike McRae for Science Alert. Looters stole much of the artwork from the tomb, but Italian Egyptologist Luigi Vassalli’s removal of the goose fresco during the late 19th century ensured its preservation.

In 2015, Kore University researcher Francesco Tiradritti published findings, based partly on the idea that some of the geese depicted were not found in Egypt, suggesting that Meidum Geese was a 19th-century fake. But as Nevine El-Aref reported for Ahram Online at the time, other scholars were quick to dismiss these arguments.

Romilio tells the Brisbane Times that it’s not unusual for millennia-old art to portray animals no longer found in modern times.

“There are examples of this from all over the world,” he says. “[I]n Australia you have paintings of thylacines and other extinct animals, in the Americas there are cave paintings of ancient elephants which used to live in that region. With Egyptian art it’s fantastic because there’s such a wealth of animals represented in their art, and usually represented fairly accurately.”

The researcher also notes that other Egyptian art shows aurochs, the extinct forebears of modern cows.

Ancient art can help scientists trace how life in a particular region has changed over time, as in the case of Egypt’s transformation from a verdant oasis into a desert climate.

“Its ancient culture emerged when the Sahara was green and covered with grasslands, lakes and woodlands, teeming with diverse animals, many of which were depicted in tombs and temples,” says Romilio in the statement.

As Lorraine Boissoneault reported for Smithsonian magazine in 2017, northern Africa became a desert between 8,000 and 4,500 years ago. The shift was partly a result of cyclical changes in Earth’s orbital axis, but some scientists argue that it was hastened by pastoral human societies, which may have eliminated vegetation with fire and overgrazed the land, reducing the amount of moisture in the atmosphere.

Romilio tells the Brisbane Times that he hopes his work sheds light on species loss, which is accelerating today.

“I think we sometimes take it for granted that the animals we see around us have been there for all our lives, and so they should be there forever,” he says. “But we’re becoming more and more aware that things do change, and we are becoming much more familiar with the idea that animals can and do go extinct.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)