Five Things to See at Alabama’s New Memorial to Lynching Victims

The memorial, along with a new museum, exposes America’s fraught legacy of racial violence from slavery to lynchings to mass incarceration

On Thursday, America’s first monument to African American lynching victims will open to the public in Montgomery, Alabama.

In a city where dozens of monuments continue to pay tribute to the Confederacy, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a powerful, evocative reminder of the scope and brutality of the lynching campaign that terrorized African American communities in the wake of the Civil War. Complementing the monument is the sprawling Legacy Museum, which traces the history of racial bias and persecution in America, from slavery to the present-day. The new institution's aim is to show that “the myth of racial inferiority” has never been fully eradicated in America, but has instead evolved over time.

The monument and museum are located a short distance from one another, and it is possible to visit both in a single day. Here are five highlights that visitors can expect to see at these groundbreaking surveys of racial violence in the United States:

1. At the six-acre memorial site, 800 steel markers pay tribute to lynching victims

Each of the markers represents a county in the United States where a lynching took place. The columns are inscribed with the names of more than 4,000 victims. The first are arranged at eye level, but as visitors enter the monument, the markers rise in height and loom over visitors’ heads—a haunting evocation of “being strung up and hanged from a tree,” intended to make visitors confront the scale and scope of lynchings, according to a recent "60 Minutes" special hosted by Oprah Winfrey.

Texts etched into the sides of the memorial tell the stories of victims like Robert Morton, who was lynched by a mob in 1897 for "writing a note to a white woman."

2. Replicas of each steel marker are arranged around the memorial, waiting to be claimed

The Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit that spearheaded the new museum and memorial, hopes that the replicas will soon be claimed and erected by the counties represented by the markers.

“Over time, the national memorial will serve as a report on which parts of the country have confronted the truth of this terror and which have not,” the monument’s website explains.

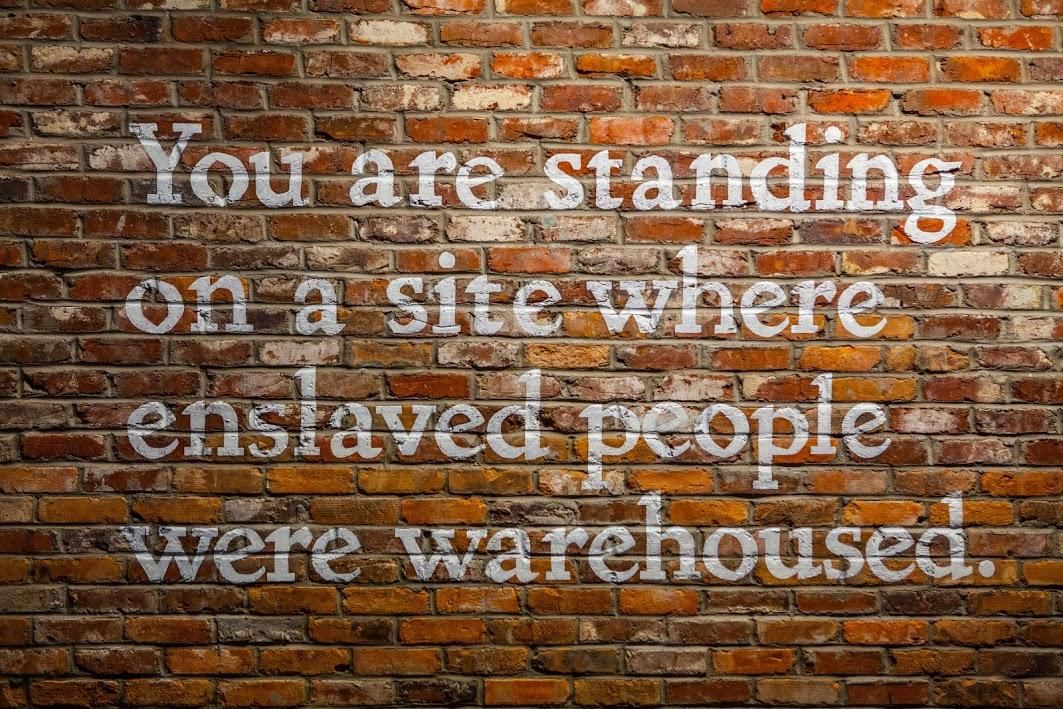

3. Inside the Legacy Museum, replicas of slave pens depict the horror of the slave trade

The new museum sits on a site in Montgomery where enslaved people were once warehoused. The warehouses were "critical to the city's save trade," according to EJI, as they were used to confine enslaved people before they were sold in auctions. The space is located a short distance from a dock and rail station where enslaved people were trafficked. Also nearby is the site of what was once one of the most prominent slave auction spaces in the United States.

Upon entering the museum, visitors are immediately confronted by the fraught history of this location. Replicas of slave pens demonstrate what it was like to be held captive while awaiting one’s turn at the auction block. The museum has also created narratives based on accounts by enslaved people, bringing human stories of the slave trade to light.

CNN senior political correspondent Nia-Malika Henderson describes listening to the story of an enslaved woman searching for her lost children during a sneak preview of the museum.

“I have to lean close, pressed up against the bars that contain her. I feel anxious, uncomfortable and penned in,” Henderson writes. “Visitors will no doubt linger here, where the enslaved, old and young, appear almost like ghosts.”

4. Formerly incarcerated African Americans tell their stories through videos built into replicas of prison visiting booths

Among the former prisoners to share their experience behind bars is Anthony Ray Hinton. Now 61 years old, he spent nearly three decades on death row after being falsely identified as the perpetrator of a double homicide when he was 29. Hinton was exonerated in 2015 with the help of attorney Bryan Stevenson, the founding director of the Equal Justice Initiative.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world; African Americans are incarcerated at more than five times the rates of whites, according to the NAACP.

“The theory behind this space is really the evolution of slavery,” Stevenson says in an interview with CBS News correspondent Michelle Miller. “Slavery then becomes lynching. And lynching becomes codified segregation. And now we're in an era of mass incarceration, where we're still indifferent to the plight of people of color.”

5. The museum features a number of powerful works by African American artists

James H. Miller of the Art Newspaper has the inside scoop on the art held in the museum's collections, including pieces by Hank Willis Thomas, Glenn Ligon, Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett and Titus Kaphar. The museum will also be home to the largest installment in a series by artist Sanford Biggers, who collects African sculptures from flea markets, shoots at then with guns and then casts them in bronze.

These statues “touch on the violence perpetuated against black bodies by the police, which goes back into all the aspects of the Legacy Museum, showing the whole pathological experience of Africans in America, from abduction in Africa to mass incarceration today,” Biggers tells Miller.

The new museum and memorial cannot single-handedly reverse these historical trends, Biggers notes. But, he says, they represent “something new and very important.”