63 Works By Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele Are at the Center of the Latest Nazi-Looted Art Dispute

The German Lost Art Foundation removed the artworks from its database, suggesting they were saved by a collector’s relatives rather than seized by Nazis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/de/3cde57b5-cc7c-4c0e-a28d-4e9457d76b29/woman_hiding_her_face.jpg)

On December 31, 1940, Austrian cabaret star Fritz Grünbaum graced the stage for the final time. It had been two years since he last performed as a free man, appearing on a pitch-black stage and proclaiming, “I see nothing, absolutely nothing. I must have wandered into the National Socialist culture.” Grünbaum’s last show, held in the Dachau concentration camp infirmary as he was dying of tuberculosis, had a less political bent. “[I] just want to spread a little happiness on the last day of the year,” he told onlookers. Two weeks later, Grünbaum was dead—killed, according to the Nazis’ euphemism-filled paperwork, by a weak heart.

In another lifetime, Grünbaum was not only a successful cabaret performer, librettist, writer and director, but an avid collector of modernist art. His trove of more than 400 works of art boasted 80 pieces by Egon Schiele, an Austrian Expressionist renowned for his confrontational portraits; it was an obvious target for the Nazis’ systematic confiscation of Jewish-owned art. Now, William D. Cohen reports for The New York Times, 63 of these Schieles are at the center of controversy surrounding the ongoing repatriation of Nazi-looted art.

Since its launch in 2015, the German Lost Art Foundation has relied on a public database to support its mission of identifying and returning illegally seized works of art. Although Grünbaum’s heirs posted the missing Schieles to the database, a renewed round of lobbying by art dealers, who argue that the works were sold without duress in the aftermath of the war, has led the foundation to remove them from the list of looted art.

“The fact that Fritz Grünbaum was persecuted by the Nazis is not contested,” foundation spokeswoman Freya Paschen tells Cohen. “This does not mean that the entirety of Grünbaum’s art collection must have been lost due to Nazi persecution.”

According to attorney and author Judith B. Prowda's Visual Arts and the Law, Grünbaum’s wife, Elisabeth, assumed control of her husband’s collection following his arrest in 1938. Under Third Reich laws, she was required to submit an inventory of Grünbaum’s assets, and, when later forced to flee from her apartment, had little choice but to release the collection to the Nazis. Soon after Grünbaum’s death in Dachau, Elisabeth was deported to a concentration camp in Minsk, where she was murdered in 1942.

Nazi records of the Grünbaum collection fail to list the names of many works, leaving their fate up for speculation. The family’s heirs argue that the works were held by the Nazis during the war, while the art dealers behind the German Lost Art Foundation’s recent decision theorize that Elisabeth managed to send the majority of the collection to relatives in Belgium prior to her arrest. Provenance laid out by Eberhald Kornfeld, a Swiss dealer who brought the 63 Schieles in question back onto the market in 1956, supports this argument, although Grünbaum’s heirs reject Kornfeld’s account as pure fiction.

Cohen writes that Kornfeld initially told buyers that he acquired the Schieles from a refugee. In 1998, he expanded on this mysterious seller’s background, identifying her as Elisabeth’s sister Mathilde Lukacs-Herzl and providing documents backing up his claim. As the Grünbaum heirs argue, however, this revelation was conveniently produced almost two decades after Lukacs-Herzl’s death, and some of the signatures on the documents are misspelled or written in pencil.

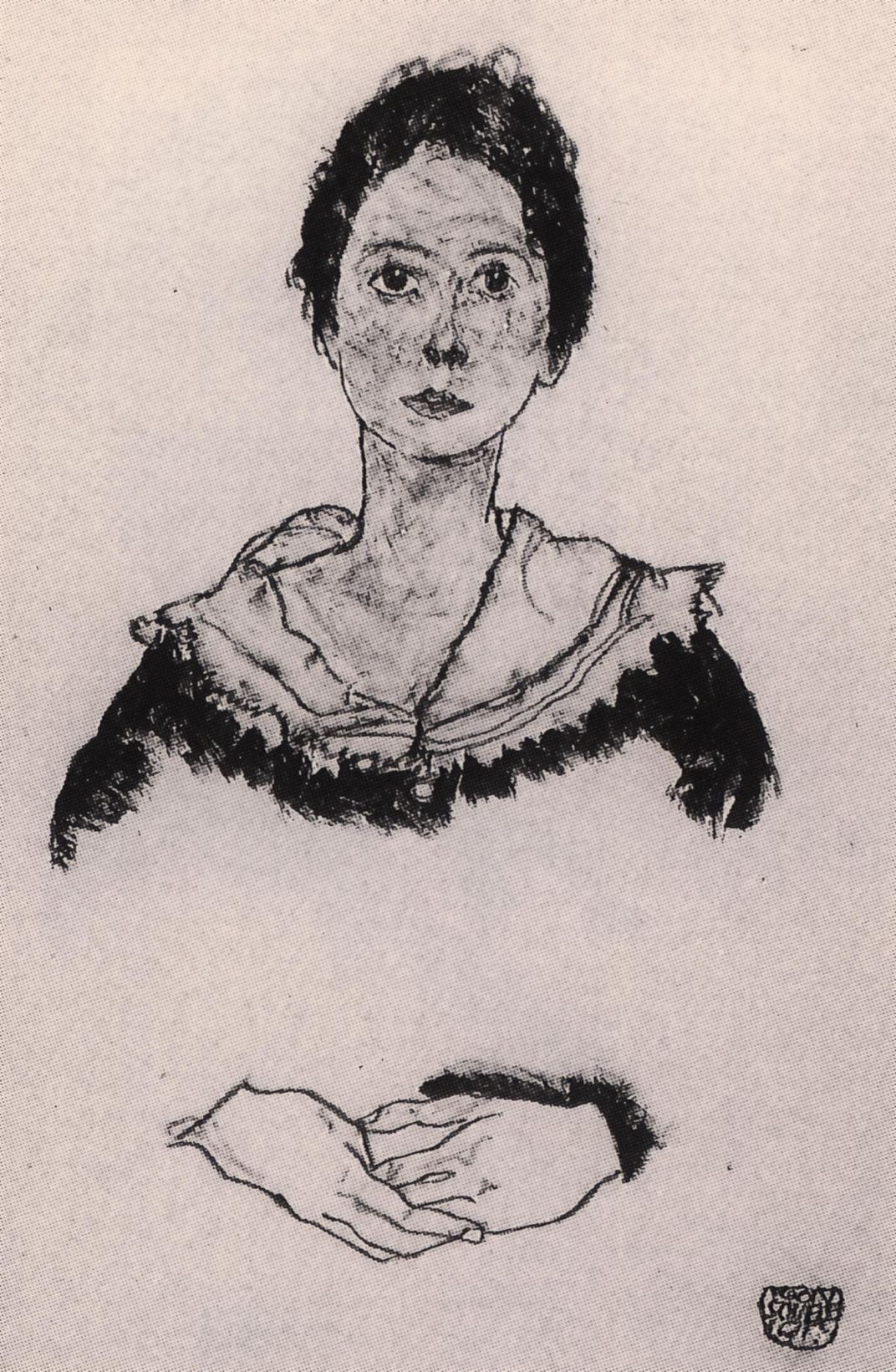

The Art Newspaper’s Anna Brady reports that in April of this year, a New York court ruled against London dealer Richard Nagy, who has long maintained that he bought two Schiele works included in Kornfeld’s sale—"Woman in a Black Pinafore” (1911) and “Woman Hiding Her Face” (1912)—legally. The judge overseeing the case, Justice Charles E. Ramos, disagreed, arguing that there was no evidence Grünbaum willingly signed his collection over to an heir, including Lukacs-Herzl.

“A signature at gunpoint cannot lead to a valid conveyance,” Ramos concluded.

The foundation’s decision to remove the Schieles from its database is especially interesting in light of the court ruling. According to the database’s guidelines, “the reporting party must plausibly demonstrate that an individual object or a collection was confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution, or was removed or lost during the Second World War, or that such a suspicion cannot be ruled out.” Ramos doubted the Schieles’ provenance enough to uphold these standards, but the foundation believes otherwise.

“Should there be new historic facts brought to light that may change the current evaluation,” foundation spokeswoman Paschen tells Cohen, “the works would be publicized again.”

For now, however, the 63 Schieles—from “Embracing Nudes,” an angular sketch of an intertwined pair rendered in the brutalistic strokes characteristic of Schiele’s work, to “Portrait of a Woman,” an eerie yet traditional black-and-white drawing of a girl whose shoulders don’t quite meet her clasped hands—will remain in limbo, trapped in an ongoing tug-of-war between heirs and dealers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)