American Scientists Took the First Photo of Earth From Space Using Nazi Rockets

70 years ago, researchers at White Sands Missile Base strapped a movie camera to a V2 rocket to get a bird’s-eye view of our planet

On October 24, 1946, researchers at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, strapped a Devry 35-millimeter movie camera into the nose of a V2 rocket captured from the Nazis and blasted it towards space. The rocket shot straight up, 65 miles into the atmosphere before sputtering to a stop and descending back to earth at 500 feet per second, reports Tony Reichhardt at Smithsonian’s Air & Space magazine. The film, protected by a steel case, returned the first images of our planet from space.

Fred Rulli, who was 19 at the time, recalled that day clearly. He tells Reichardt that he was assigned to the recovery team that drove out into the desert to retrieve the film canister from the missile wreckage. When they found that the film was intact, Rulli says the researchers were thrilled. “They were ecstatic, they were jumping up and down like kids,” he says. After the recovery, “when they first projected [the photos] onto the screen, the scientists just went nuts.”

The photo itself is grainy, showing clouds over the Southwest. And though may not have yielded much data, it was an impressive proof of concept. Prior to the V2 launch, Becky Ferreira at Motherboard reports that the highest photo ever taken came in 1935 from Explorer II, a hot air balloon mission sponsored by the Army Air Corps and the National Geographic Society. That two-man crew was able to take photos from an altitude of 13.5 miles.

But less than a year after the first V2 photos, researchers at White Sands led by physicist John T. Mengel were able to take images from over 100 miles up. In all, between 1946 and 1950, researchers collected over 1,000 images of earth from space aboard the V2 rockets.

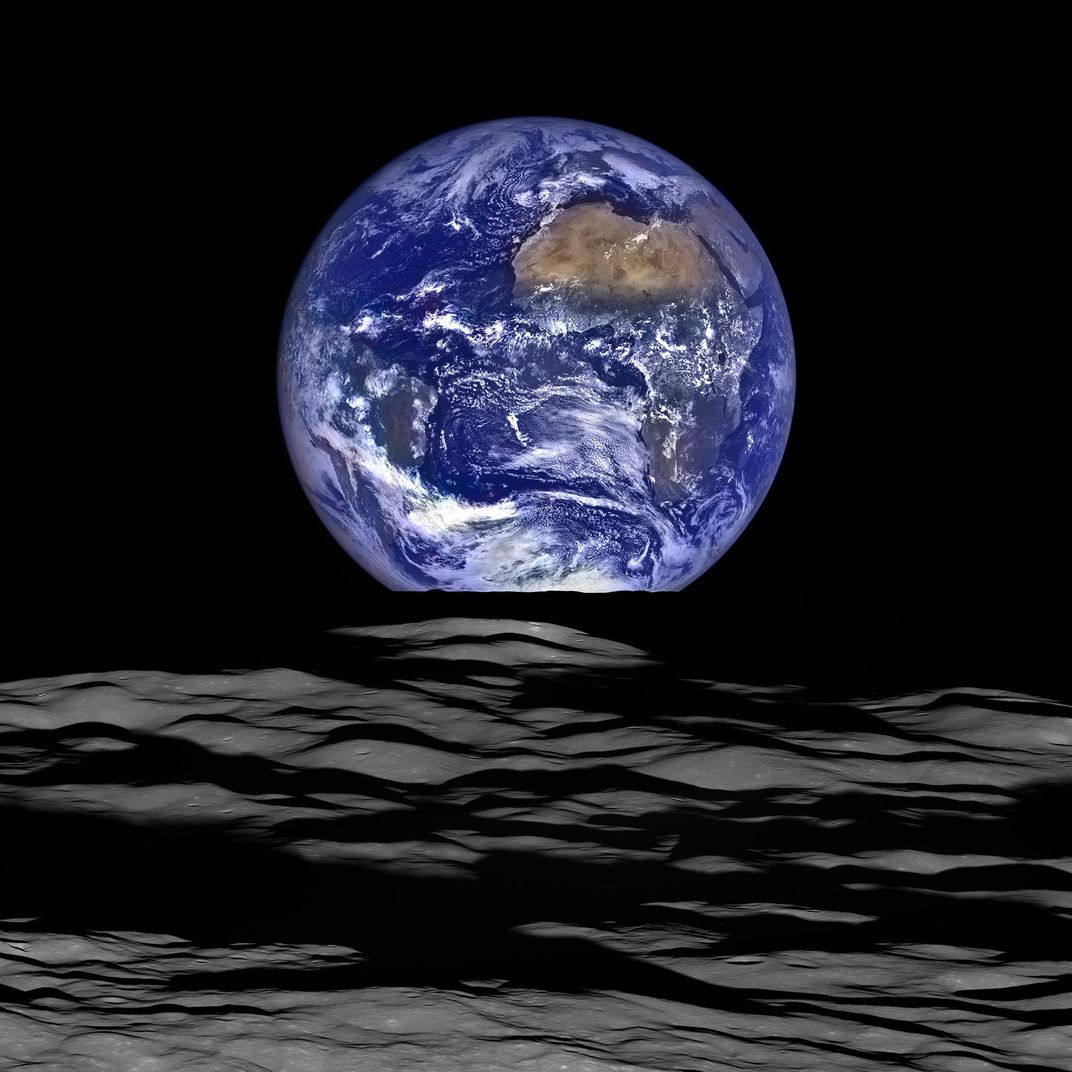

Over time, of course, imaging Earth from space has gotten much more sophisticated, giving humanity new perspectives on our little blue marble. On Christmas Eve, 1968, for example, during the Apollo 8 Mission, which circled the moon, astronaut Bill Anders remembers orbiting the moon and marveling at its surface. It was his job to shoot camera images out of the window. But once the spacecraft flipped around into a new position, revealing Earth, all three men aboard the craft were astonished. The other two astronauts started calling for cameras, even though photographing Earth was not part of their mission brief. They all started snapping away, with Anders capturing an image called “Earthrise” which stunned the world and is credited with helping fan the flames of the nascent environmental movement.

The “Pale Blue Dot" is another image that, perhaps not quite as aesthetically pleasing as Earthrise, gave stunning perspective on the planet. Shot in 1990 from Voyager 1 in the space beyond Neptune, it contains a tiny speck that could be dust on the lens. But that's no dust; it’s Earth, as seen from 40 astronomical units away.

In his book named after the image, Carl Sagan wrote: “That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. … There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world.”

In the last decade, the images have grown increasingly high tech. For instance, in NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter captured a new version of “Earthrise” in 2015. But this time, instead of an astronaut using a handheld camera and shooting out a capsule window, it was taken with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera. First, a narrow-angle camera took black and white images while a wide angle camera shot the same images in color—all while traveling at 3,580 miles per hour. Back on Earth, special imaging software was able to combine the two images to create the high-resolution image of the lunar surface with Earth in the distance. It may not be as world changing as the first Earthrise image, but it definitely gives a clear-eyed view of how far we've come.