This Prehistoric Peruvian Woman Was a Big-Game Hunter

Some 9,000 years ago, a 17- to 19-year-old female was buried alongside a hunter’s tookit

:focal(498x475:499x476)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/7d/ed7d7e24-2601-4eb8-9d75-93ff64acf872/woman-hunter-new-image.jpg)

Archaeologists in Peru have found the 9,000-year-old skeleton of a young woman who appears to have been a big-game hunter. Combined with other evidence, the researchers argue in the journal Science Advances, the discovery points to greater involvement of hunter-gatherer women in bringing down large animals than previously believed.

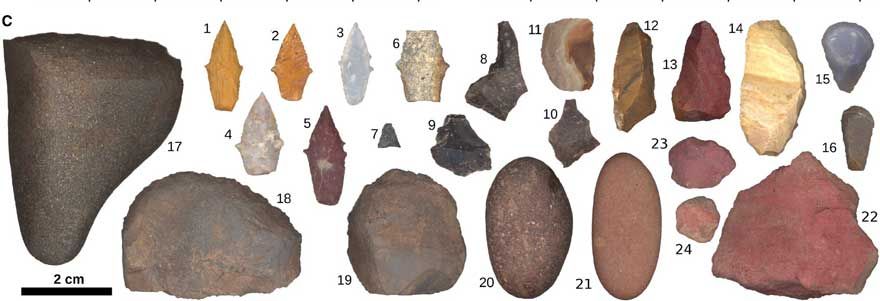

The team found the grave at Wilamaya Patjxa, a high-altitude site in Peru, in 2018. As lead author Randall Haas, an archaeologist at the University of California, Davis, tells the New York Times’ James Gorman, he and his colleagues were excited to find numerous projectile points and stone tools buried alongside the skeletal remains.

Originally, the researchers thought that they’d unearthed the grave of a man.

“Oh, he must have been a great chief,” Haas recalls the team saying. “He was a great hunter.”

But subsequent study showed that the bones were lighter than those of a typical male, and an analysis of proteins in the person’s dental enamel confirmed that the bones belonged to a woman who was probably between 17 and 19 years old.

Per the paper, the hunter was not a unique, gender nonconforming individual, or even a member of an unusually egalitarian society. Looking at published records of 429 burials across the Americas in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene epochs, the team identified 27 individuals buried with big-game hunting tools. Of these, 11 were female and 15 were male. The breakdown, the authors write, suggests that “female participation in big-game hunting was likely non-trivial.”

As Bonnie Pitblado, an archaeologist at the University of Oklahoma, Norman, who was not involved in the study, tells Science magazine’s Ann Gibbons, “The message is that women have always been able to hunt and have in fact hunted.”

The concept of “man the hunter” emerged from 20th-century archaeological research and anthropological studies of modern hunter-gatherer societies. In present-day groups like the Hadza of Tanzania and San of southern Africa, men generally hunt large animals, while women gather tubers, fruits and other plant foods, according to Science.

Many scholars theorized that this division was universal among hunter-gatherers.

“Labor practices among recent hunter-gatherer societies are highly gendered, which might lead some to believe that sexist inequalities in things like pay or rank are somehow ‘natural,’” says Haas in a statement. “But it’s now clear that sexual division of labor was fundamentally different—likely more equitable—in our species’ deep hunter-gatherer past.”

Not everyone is convinced of the new paper’s thesis. Robert Kelly, an anthropologist at the University of Wyoming who wasn’t involved in the research, tells Science that though he believes the newly discovered skeleton belongs to a female hunter, he finds the other evidence less convincing.

Kelly adds that the discovery of hunting tools at a gravesite does not necessarily indicate that the person buried there was a hunter. In fact, he says, two of the burials found at Upward Sun River in Alaska contained female infants. In some cases, male hunters may have buried loved ones with their own hunting tools as an expression of grief.

Speaking with National Geographic’s Maya Wei-Haas, Kathleen Sterling, an anthropologist at Binghamton University in New York who was not part of the study, points out that researchers likely wouldn’t have questioned the tools’ ownership if they’d been buried with a man.

“We typically don’t ask this question when we find these toolkits with men,” she observes. “It’s only when it challenges our ideas about gender that we ask these questions.”

According to Katie Hunt of CNN, recent research suggests that hunting in at least some hunter-gatherer societies was community-based. Around the time the newly discovered individual lived, the hunting tool of choice was the atlatl, a light spear-thrower used to bring down alpaca-like animals called vicuña. Because the device was relatively unreliable, communities “encouraged broad participation in big-game hunting,” working together to “mitigate risks associated with … low accuracy and long reloading times,” per the study. Even children wielded the weapon, perfecting their technique from a young age.

“This study should help convince people that women participated in big-game hunts,” Sterling tells Live Science’s Yasemin Saplakoglu. “Most older children and adults would have been needed to drive herds over cliffs or into traps, or to fire projectiles at herds moving in the same direction.”

For the Conversation, Annemieke Milks, an archaeologist at University College London who also wasn’t involved in the study, writes that researchers are increasingly calling into question aspects of the “man-the-hunter” model. In the Agata society of the Philippines, for example, women take part in hunting. And among present-day hunter-gatherers who use atlatls, women and children often take part in competitive throwing events.

Scientists have long argued that men across societies hunted while women stayed closer to home, making it easier for mothers to care for their children. Today, however, some researchers note that these claims may reflect the stereotypes of 20th-century United States and Europe, where they emerged. Growing bodies of research suggest that that child care in many hunter-gather societies was shared by multiple people, a system known as alloparenting.

Marin Pilloud, an anthropologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, who was not a part of the study, tells Live Science that many cultures don’t share the same concept of the gender binary as modern Americans and Europeans.

She adds, “When we step back from our own gendered biases can we explore the data in nuanced ways that are likely more culturally accurate.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)