A “Merbot” Retrieved Artifacts From Louis XIV’s Sunken Flagship

The humanoid diving robot could help researchers explore fragile wrecks from the surface of the sea

For decades, scientists have used robotic submersibles to explore the ocean’s depths. For the most part, these machines are still clunky and klutzy, lacking the dexterity of a human diver. Now, a group of roboticists at Stanford University have created a humanoid "merbot" with nearly the dexterity of human hands. The robot, dubbed "OceanOne," recently showed off its nimbleness by retrieving several artifacts from a 17th-century shipwreck that once belonged to Louis XIV, Becky Ferreira reports for Motherboard.

French officials have long known about the wreck of La Lune, but because the 352-year-old shipwreck is so fragile, divers and underwater archaeologists have avoided disturbing it. The 17th-century ship was once the flagship of Louis XIV’s fleet until 1664, when returning from a trip to North Africa, the ship abruptly sunk off the coast of Toulon. The tragedy not only destroyed the pride of Louis’ fleet, but killed approximately 700 people, leading the Sun King to downplay the news, Ferreira reports. The sunken ship, however, provided a great opportunity to test out the merbot's capabilities.

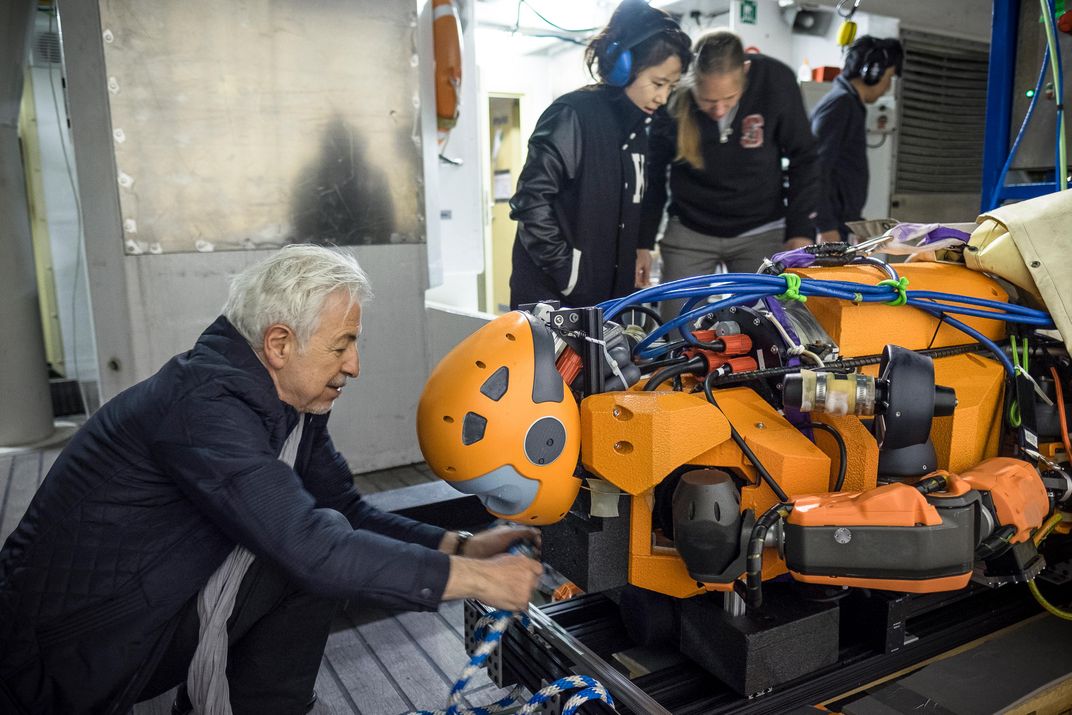

OceanOne was originally designed to survey coral reefs due to concerns that standard diving robots could accidentally damage the delicate ecosystems. There is no standard size or shape for typical remote-operated underwater vehicles (ROVs), but for the most part they are larger than a human and have arms that are controlled by joysticks from humans aboard a nearby ship. OceanOne, on the other hand, is about five feet long and has arms that are powered by a sophisticated system that lets operators use their own physical movements to control them as if they are actually there, Ferreira reports.

“OceanOne will be your avatar,” Stanford computer scientist Oussama Khatib, who led the team behind OceanOne said in a statement. “The intent here is to have a human diving virtually, to put the human out of harm’s way. Having a machine that has human characteristics that can project the human diver’s embodiment at depth is going to be amazing.”

While this technology could have been adapted for standard ROVs, OceanOne’s humanoid shape makes it easier for human operators to handle. Each of its eyes hides a camera that are positioned where a human’s eyes would be, giving its operator a better perspective than if they were looking through a single lens. At the same time, its arms are positioned in similar places as on a human body, to make it feel more natural to operate them. To top it off, the robot’s arms incorporate haptic feedback that allows the user to “feel” what the robot feels, allowing them to control its grip without crushing an object, Evan Ackerman writes for IEEE Spectrum.

“We connect the human to the robot in very intuitive and meaningful way,” Khatib said in a statement. “The two bring together an amazing synergy. The human and robot can do things in areas too dangerous for a human, while the human is still there.”

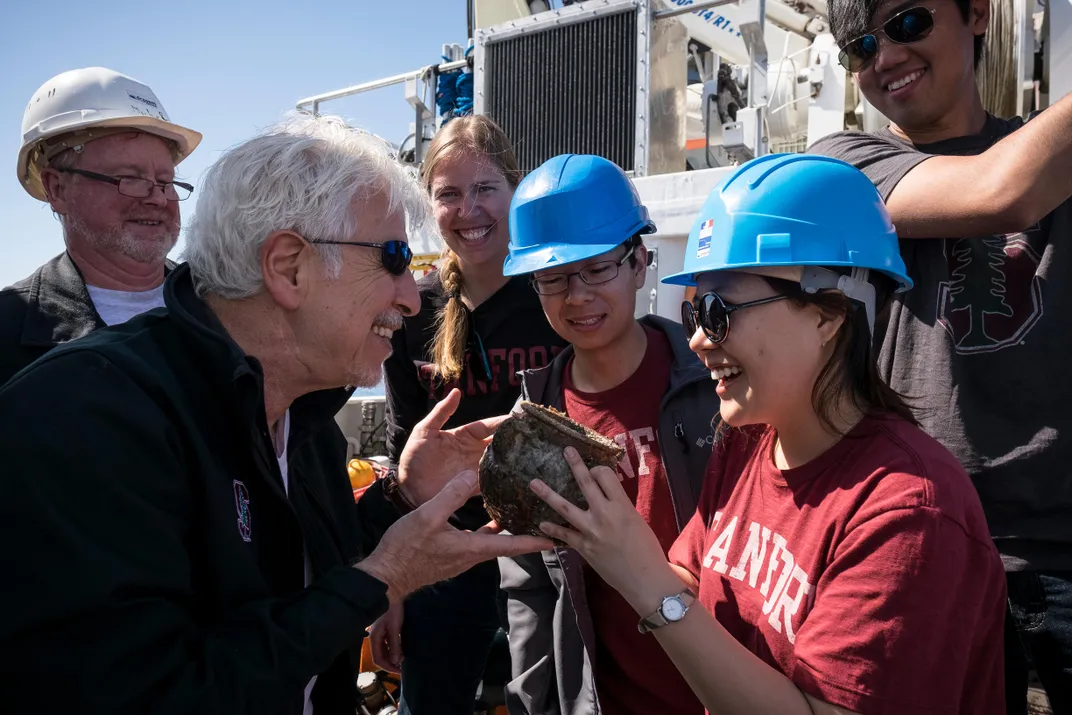

OceanOne's spin in the wreckage of La Lune was the merbot's maiden voyage, and it successfully retrieved several objects, including a vase that went down with the ship. At one point, the robot got wedged between two cannons, but Khatib was able to free it by taking control of its arms and pushing it to freedom, according to a statement.

Now that OceanOne has demonstrated its value in underwater archaeology, Khatib and his team hope to use it and future humanoid diving robots to explore delicate coral reefs that are too deep for humans to safely dive.