Scientists Discover “Super-Colony” of 1.5 Million Adélie Penguins in Images From Space

In other areas of the Antarctic, the black and white birds are in decline—but on the Danger Islands, they thrive

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/73/8b733a82-4a89-486e-9c5d-10d931335c10/danger_islands_expedition_image_9.jpg)

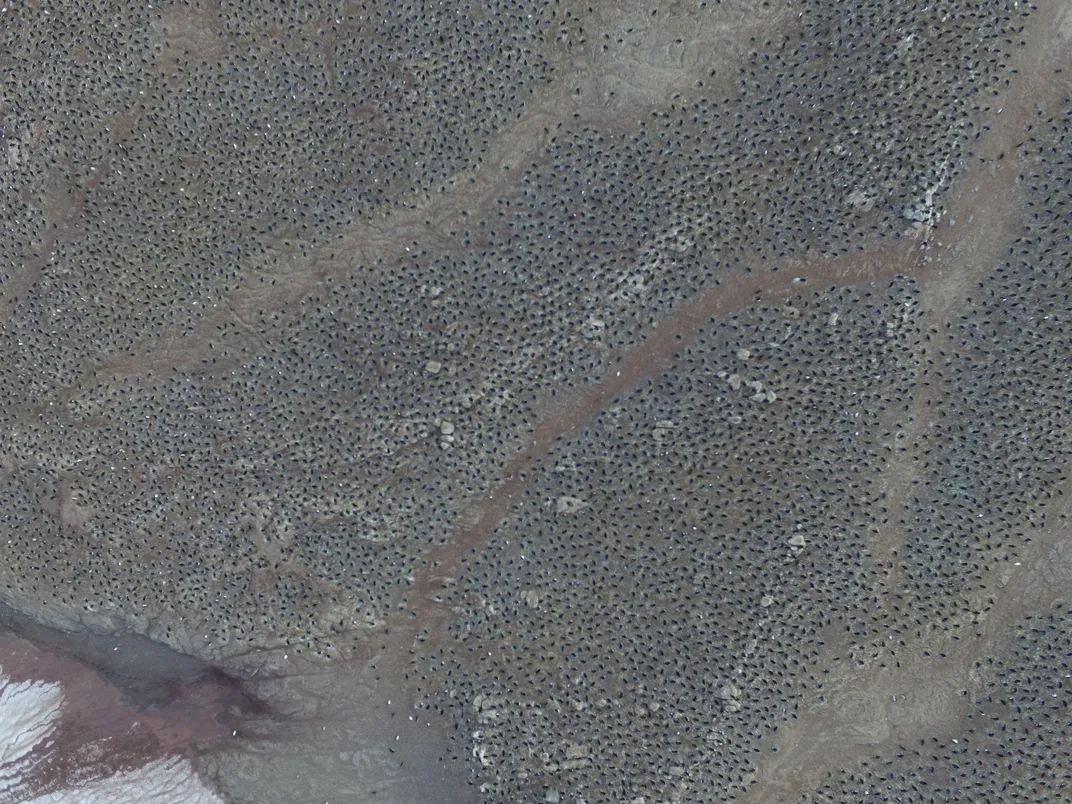

Captured in satellite images, the white stretches of penguin poop stood in stark contrast to the brown rocky surface of Danger islands, a remote archipelago located off the northernmost tip of the Antarctic peninsula. It's not commonly thought to be a popular penguin spot, but the poop was a telltale sign that the black and white birds waddled nearby.

Even so, as Jonathan Amos and Victoria Gill report for BBC News, when scientists ventured out, what they found surprised them: Around 1.5 million Adélie penguins were thriving in these far flung nesting grounds, grouped in some of the largest known colonies of the birds in the world.

A team of scientists led by ecologist Heather Lynch of Stony Brook University in New York first spotted signs of penguin activity in 2014 when using an algorithm to search through images from the Landsat satellite, a craft jointly managed by the USGS and NASA. Though Landsat does not offer particularly clear images, the researchers were surprised when they saw such a large area spotted with penguin poop, Robert Lee Hotz reports for The Wall Street Journal. A year later, another team visited the location and discovered a far larger population of Adélie penguins than they had ever imaged.

Researchers counted penguins by hand but also used drone imagery to scan large portions of the island. They counted 751,527 pairs of Adélie penguins, as detailed Friday in the journal Scientific Reports.

Tom Hart from Oxford University, who was part of the team investigating the penguin populations, tells the BBC: "It's a classic case of finding something where no-one really looked! The Danger Islands are hard to reach, so people didn't really try that hard.”

This new discovery comes in sharp contrast to the current state of other species of penguins in the Antarctic. Earlier this week, a report suggested that the king penguin population, which can breed on just a few islands in Antarctica, could suffer up to a 70 percent decline by 2100 if they don’t find a new home.

Until now, researchers thought the Adélie penguin was suffering a similar fate as a result of climate change. As the BBC reports, Adélie penguin populations on other parts of Antarctica are in decline, especially on the western side of the continent. A 2016 report even suggested that Adélie colonies could decline by up to 60 percent by the end of the century. Scientists have linked the plunging numbers to a reduction in sea ice and warming sea temperatures, which have severely impacted krill populations, the penguin’s main source of food.

But the new report shows a different story. As Lynch tells Hotz that the Adélie penguins population has been stable on the Danger Islands since the 1950s, as evidenced by aerial photos of the region from 1957.

According to Hotz, the populations is likely protected by a thick section of sea ice that isolates the islands and prevents fishing fleets from depleting the penguin's food sources. But that's just one reason for the surprising health of the super colony—researchers aren’t exactly sure why they've been spared the struggles of other populations, Brandon Specktor writes for Live Science.

As Specktor reports, the international Commission for the Conservation of the Antarctic Marine Living Resources is considering a proposal to recognize the Danger Islands as a marine protected area, or MPA, where human activity is limited for conservation purposes.

This new study provides evidence that conservation efforts are needed, Rod Downie, head of polar programs at conservation organization World Wildlife Fund, tells The Independent’s Josh Gabbatiss.

“This exciting discovery shows us just how much more there still is to learn about this amazing and iconic species of the ice,” Downie says. “But it also reinforces the urgency to protect the waters off the coast of Antarctica to safeguard Adélie penguins from the dual threats of overfishing and climate change.”

Scientists now believe more than 4.5 million breeding pairs of Adélie penguin population exist in Antarctica today, about 1.5 million more than they estimated 20 years ago.

Editor's Note March 5, 2018: The headline of this article has been changed to clarify that the penguins were identified in images taken in space.