After a Century, an Anthropologist Picked up the Trail of the “Hobo King”

One hundred-year-old graffiti by “A-No.1” and others were found by the L.A. River

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/ec/f6ecc14b-4bf5-4605-b1f0-24e570f955f6/tramp.jpg)

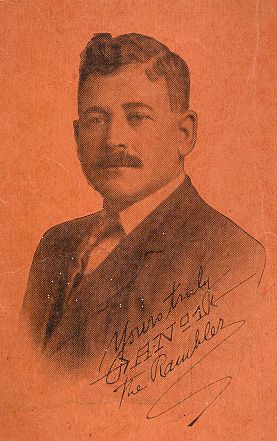

Recently, anthropologist Susan Phillips was searching the sides of the Los Angeles River for graffiti left behind by street artists and gang members when she came across scribbles and signatures of a different sort. Most of the artwork she studies is made with spray paint, but a particular patch of markings left beneath a bridge were etched with grease pencils and knife points. She recognized the symbols and signatures as those that would have been left behind about a century ago by transient people, including one by a man who is perhaps the best-known of the 20th century’s vagabonds: Leon Ray Livingston, better known as “A-No.1.”

If there is anyone who deserves to be called “the hobo king,” A-No.1 best suits the bill. Livingston spent much of his life traveling the United States by boxcar, writing several books about his journeys and working short stints as a laborer. But among historians of the era, he is known for developing and disseminating the coded symbols and markings that passed along local tips to fellow itinerant travelers, Sarah Laskow writes for Atlas Obscura. One of Livingston’s books, which chronicled his journeys with writer Jack London, eventually became the basis for the 1973 film Emperor of the North, starring Lee Marvin as A-No.1.

“Those little heart things are actually stylized arrows that are pointing up the river,” Phillips tells John Rogers for the Associated Press as she pointed out scribbled markings alongside Livingston’s signature. “Putting those arrows that way means ‘I’m going upriver. I was here on this date and I’m going upriver.’”

Although so-called hobo graffiti has mostly disappeared from America’s signposts and walls, the coded markings were once common sights across the country. The symbols often indicated safe places to gather, make camp and sleep, or might warn fellow travelers of danger or unfriendly locals, Elijah Chiland writes for Curbed Los Angeles. In this case, it appears that A-No.1 was heading upriver toward Los Angeles' Griffith Park around August 13, 1914, which was a popular place for other nomadic people to meet.

Considering how quickly modern graffiti is washed away or painted over by other taggers, it seems like a minor miracle that the marks made by Livingston and his contemporaries somehow survived in this little corner of the L.A. River. After all, it was never intended to stick around very long, and the work by the Army Corps of Engineers in the late 1930s to lower the river to prevent or reduce its periodic floods was thought to have destroyed much of what once sat on its riverbanks. However, it appears that construction work is what may have preserved the 100-year-old graffiti for all this time as it rendered much of the area beneath the bridge inaccessible to future graffiti writers, Chiland writes.

“It’s just like a fluke down there in L.A. that that survived,” Bill Daniel, who studies historic graffiti and modern taggers, tells Rogers. “It’s hard to find the old stuff because most older infrastructure has been torn down.”

While it’s impossible to verify whether the name A-No.1 was scratched into the wall by Livingston himself or by someone else using his name, Phillips found other remarkable examples of graffiti made by the Hobo King’s contemporaries. Signatures and drawings belonging to people with names like “Oakland Red” and “the Tucson Kid” cover the space beneath the bridge alongside the famous A-No.1, Rogers reports. Now that the spot has been publicized, though, Phillips is working to chronicle the work while she still can.

“A lot of the stuff I’ve documented through time has been destroyed, either by the city or by other graffiti writers,” Phillips tells Rogers. “That is just the way of graffiti.”