Allergy Season Is Getting Longer and Nastier Each Year

An extended and intensified allergy season is one of the most visible effects of climate change

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/6d/676d9e35-1557-48aa-a9d0-1dd8124d4f1d/istock-468417638.jpg)

If you have seasonal allergies, you may have already suspected that allergy season is coming earlier, lasting longer and growing more severe in the last two decades. Now, there’s science to back up that hunch.

The upswing in allergens is a global phenomenon, reports Umair Irfan at Vox, with pollen counts increasing across the Northern Hemisphere in the last 20 years—an uptick likely fueled by climate change. And that’s a big deal; between 10 and 30 percent of the global population, including 50 million Americans, suffer from seasonal allergies.

In a new study published in the journal The Lancet Planetary Health, researchers analyzed pollen counts in 17 locations worldwide stretching back an average of 20 years. Of those locations, 12 saw significant increases in the pollen load over time. The international team hypothesizes that the upswing in pollen is related to changes in maximum and minimum temperatures caused by climate change.

The intensification of allergy season is one of the earliest and most visible public health impacts of climate change, Irfan reports. “It’s very strong. In fact, I think there’s irrefutable data,” Jeffrey Demain, director of the Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Center of Alaska, not involved in the study, tells Vox’s Irfan. In Alaska, which is warming twice as fast as other parts of the globe, pollen is up as well as stings by insects.

“It’s become the model of health impacts of climate change,” Demain says.

So why are pollen counts going off the charts? According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, there are three main reasons. First, rising CO2 levels truly do have a greenhouse effect, increasing the growth rate of many plants which leads to more pollen. Rising temperatures extend the growing season of pollen-producing plants. And longer spring seasons lengthen the pollen production of certain plants and allows more fungal spores to make it into the air.

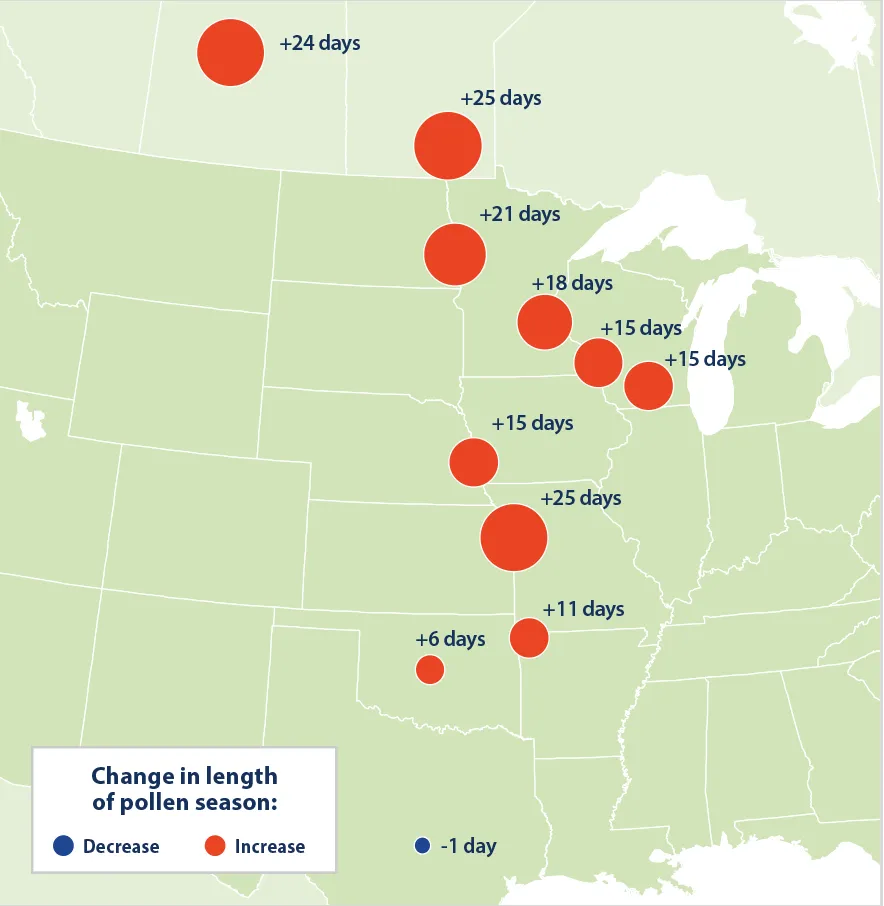

Temperatures are expected to rise by 3-to-4 degrees Fahrenheit and carbon dioxide concentrations could reach 450 parts per million by 2050. Lewis Ziska, lead author of the study and a weed ecologist at the United States Department of Agriculture, under those conditions, some pollen producers will thrive. He predicts, for example, that ragweed, which is usually about five to six feet tall, could shoot up to ten, or even 20, feet tall in some cities, producing much larger amounts of pollen—a true nightmare for hay fever sufferers. In fact, Ziska tells Irfan that since pre-industrial times, the pollen productivity of ragweed has already doubled. And according to data from the Environmental Protection Agency, ragweed hangs around between 11 to 25 days longer than it did in 1995.

“The influence of climate change on plant behavior exacerbates or adds an additional factor to the number of people suffering from allergy and asthma,” Ziska tells the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Ragweed is not the only species of concern. Tree pollen, grass pollen and molds are all major allergy triggers, all of which are expected to double by 2040. This year is already off to a pretty apocalyptic start with images of dense pollen clouds over North Carolina making the rounds and Chicago bracing for a bad allergy season.

Korin Miller at Prevention says installing a new air filter, keeping houses clean, avoiding yard work on high-pollen days and taking over-the-counter allergy medication can keep people from experiencing allergy attacks. But for many sufferers the best strategy is getting immunotherapy shots, which eventually desensitize the immune system to allergens. And for needle-phobes, there’s good news. NPR reports that many allergists are prescribing immunotherapy tablets for people suffering from grass pollen, dust mite or ragweed allergies.