Although Less Deadly Than Crinolines, Bustles Were Still a Pain in the Behind

“The woman with a bustle can never sit down in a natural position,” one 1880s doctor wrote

:focal(1560x255:1561x256)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/2d/662d24a1-0680-441b-8ad8-b9f6731fc5a4/bustle.jpg)

Victorian fashionistas were in search of an ideal silhouette, and they’d go to great lengths to get it.

Among the many bizarre crimes that nineteenth-century women’s fashion is known for (see also: the steel-boned corset, the tapeworm diet and the leg o’mutton sleeve), the crinoline and its younger, less deadly cousin, the bustle stand out. On this day in 1857, a New York man named Alexander Douglas patented the bustle.

It took almost another decade for Douglas’s invention to gain in popularity. During this decade, the fashion world reached the heights of the skirt-circumference arms race that characterized mid-nineteenth-century women’s fashion.

“Fashionable dress in the 19th century went through several silhouette changes from tubular to hourglass and back to tubular,” writes Marlise Schoeny at the Ohio State University’s historical costumes and textiles blog. “The fashion of the dress silhouette was not dependent on the natural human body but rather on a range of undergarments including chemise, petticoats, hoops, bustles and corsets to create an artificial shape.”

Over the course of that century, Schoeny writes, reformers ranging from feminists to health advocates and doctors became concerned that “women’s clothing, particularly fashionable dress, was harmful to women’s health.” A look at the era’s improbable skirts shows why:

The Crinoline

The crinoline (its name was a combination of “crin,” the name for a stiff horsehair fabric, and “linen”) entered the fashion arena in the mid-1800s, writes the National Museum of Scotland. “But it wasn’t the stiff fabric that gave the crinoline its remarkable silhouette; it was the under-hoops, made of bone or even steel, which formed a cage.”

"Crinolinemania," as Punch magazine referred to it, took over, with factories producing thousands upon thousands of the items. But besides being deeply inconvenient to move around in, crinolines literally trapped the wearer in a large cage that was difficult to escape from and covered in flammable fabric at a time when open flame was common. “From the late 1850s to the late 1860s around 3,000 women died in crinoline fires in England.”

By the mid-1860s, the museum writes, the crinoline had already begun to be replaced by the bustle. As city living became more common and women spent more time in public, the crinoline was simply not feasible.

The Bustle

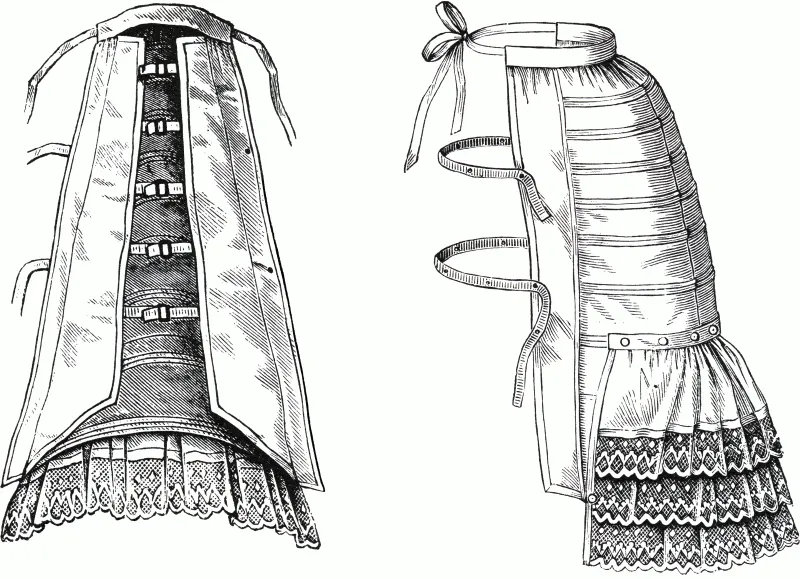

At some point in the 1860s, the trend for crinolines began to move more towards an oval design that gave the wearer a flat front but stuck out behind. Only natural, then, that fashion would shift towards the less-space-consuming bustle. The introduction of the bustle, writes the University of Vermont, “changed the shape of the entire dress, not just the back. The sides of the skirt were drawn further back, creating a narrower front.” Bustles were initially set high but then lowered and, eventually, phased out altogether.

An 1888 anonymous writer to the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal voiced concerns about the fashion of the time in a letter headed simply “Bustles.”

The writer reels off the numerous health problems they see with everyday women’s fashion: corsets squeezing organs, shoes too small and pointed at the toe deforming the foot and particularly the bustle. “The woman with a bustle can never sit down in a natural position,” the letter records. “It is absolutely impossible for her to rest her back against the back of any seat of ordinary construction. I have no doubt some of the severe backaches in women whose duties keep them seated all day are due to, or at least aggravated by, this disability.”

The bustle, as the Victoria and Albert Museum documents, went out of fashion around 1888 and—unlike the crinoline, which can occasionally reappear as wedding garb–hasn't come back.