Amateur Treasure Hunter in England Discovers Early Medieval Sword Pyramid

On par with specimens found at nearby Sutton Hoo, the tiny accessory likely helped a lord or king keep their weapon sheathed

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4e/ba/4ebab96e-8bc1-4cbd-9b4c-9c4436edd112/sword_mount.jpg)

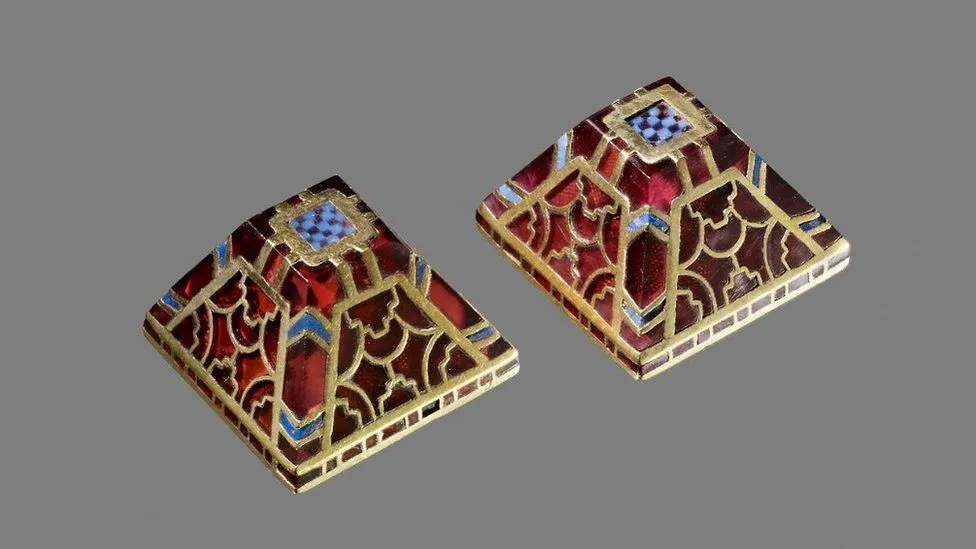

In April, amateur metal detectorist Jamie Harcourt unearthed a gold and garnet sword pyramid—a decorative fitting likely used to help keep weapons sheathed—that may have belonged to a wealthy lord or early medieval king. Found in the Breckland district of Norfolk, England, the object “bears a striking resemblance” to artifacts found in the nearby Sutton Hoo burial, reports Treasure Hunting magazine.

According to BBC News, the tiny adornment dates to between roughly 560 and 630 C.E., when the area was part of the Kingdom of East Anglia. Sword pyramids usually come in pairs, but this one was found alone, meaning its owner may have misplaced it while “careening around the countryside.”

Helen Geake, a finds liaison officer with the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), which records archaeological finds made by the British public, tells BBC News that its loss “was like losing one earring—very annoying.”

Shaped like a pyramid with a truncated peak, the artifact’s square base measures less than half an inch on each side, per its PAS object record. The pyramid’s four faces feature two distinct designs, both of which boast inlaid garnets probably imported from India or Sri Lanka.

These gemstones’ presence speaks to the existence of far-reaching trade networks between Europe and Asia in the sixth and seventh centuries, Geake says.

“[The sword pyramid] would have been owned by somebody in the entourage of a great lord or Anglo-Saxon king, and he would have been a lord or thegn [a medieval nobleman] who might have found his way into the history books,” she tells BBC News. “They or their lord had access to gold and garnets and to high craftsmanship.”

Pyramid mounts are relatively common medieval English artifacts. Historians are unsure of their exact purpose, but Art Fund notes that they were “associated with Anglo-Saxon sword scabbards and [likely] used to help keep” swords in their sheaths.

“It’s believed [the mounts] made it a bit more of an effort to get the sword out of the scabbard, possibly acting as a check on an angry reaction,” Geake says to BBC News.

Not typically discovered in graves, sword pyramids are becoming “increasingly common as stray finds (perhaps accidental losses),” according to PAS. Surviving examples can be categorized by shape (from pyramidal to cone-like); material (copper alloy, silver or gold); and decorative style.

The newly unearthed specimen is contemporaneous with Sutton Hoo, a famed royal burial that fundamentally changed archaeologists’ view of the “Dark Ages.” The Dig, a Netflix film based on the Sutton Hoo excavations, brought renewed attention to the site upon its release earlier this year.

Uncovered in Suffolk in 1939, the early medieval cemetery contained around 18 burial mounds dated to the sixth or seventh century. Artifacts recovered from the Sutton Hoo graves ranged from helmets to silverware from Byzantium to rich textiles to sword pyramids.

“[Sutton Hoo] embodied a society of remarkable artistic achievement, complex belief systems and far-reaching international connections, not to mention immense personal power and wealth,” says Sue Brunning, curator of early medieval European collections at the British Museum, in a statement. “The imagery of soaring timber halls, gleaming treasures, powerful kings and spectacular funerals in the Old English poem Beowulf could no longer be read as legends—they were reality, at least for the privileged few in early Anglo-Saxon society.”

Speaking with Treasure Hunting, Harcourt describes the Norfolk sword pyramid as the “find of a lifetime.”

“It is very similar to those examples recovered during the world famous 1939 excavation at Sutton Hoo,” he says, as quoted by Alannah Francis of inews. “The garnet workmanship is also reminiscent of several items in the Staffordshire Hoard matrix.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)