Ancient Chinese Graves Reveal Evidence of Early Skull Reshaping

Humans may have compressed infants’ soft heads with their hands, bound them between boards or wrapped them tightly in cloth

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/89/61892ccd-6e92-421f-a6fe-a0b6d7c5d696/modified-adults.jpg)

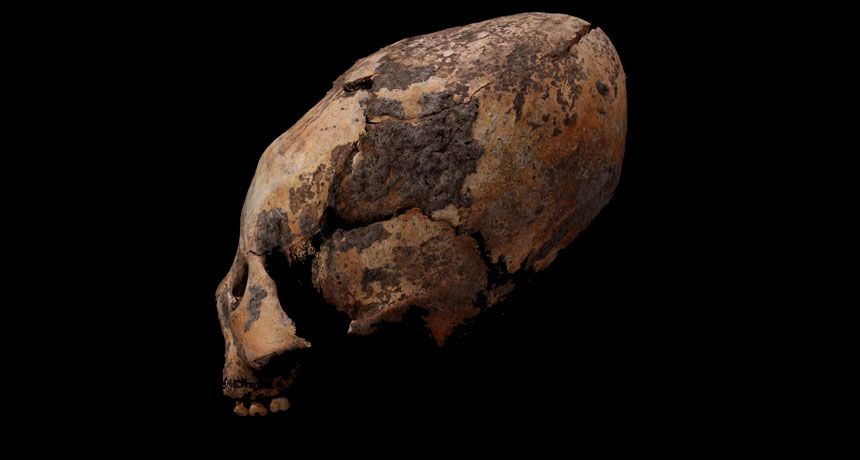

Human skeletons unearthed at the Houtaomuga archaeological site in northeast China represent some of the earliest evidence of intentional skull reshaping, a new study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology reports.

As Bruce Bower writes for Science News, 11 modified skulls, excavated alongside 14 skeletons with unmodified craniums between 2011 and 2015, have artificially elongated braincases and flattened bones at both the front and back of the head. Per the study, five of the skulls belonged to adults (four men and one woman), and six belonged to children. Ages ranged from as young as 3 years old to as old as 40. Of the skulls, one was found in a layer of sediment dating to around 12,000 years ago, while the remaining 10 were found in sediment dating to between 6,300 and 5,000 years ago.

As Science Alert’s Michelle Starr explains, intentional cranial modification (ICM), also known as artificial cranial deformation, has been practiced around the world for millennia, albeit for a number of different reasons. Some cultures likely participated in skull reshaping as an indicator of social status, wealth and power, while others may have inadvertently modified infants’ heads by binding them to protect during growth.

The earliest-known example of ICM was long assumed to be a pair of 45,000-year-old Neanderthal skulls found in Iraq and formally described in 1982, but these findings have since been questioned, and several 13,000-year-old Australian skulls are now viewed as more likely candidates for oldest specimens identified to date.

Although Houtaomuga is not home to the earliest evidence of ICM, researchers led by bioarchaeologist Quanchao Zhang of China’s Jilin University and paleoanthropologist Qian Wang of Texas A&M University say it does hold the distinction of recording skull modifications that occurred over a longer stretch of time than seen at any other excavation site.

To reshape the skull, these early humans may have compressed infants’ soft heads with their hands, as Bower explains for Science News. It’s also possible they bound the head between boards or wrapped it tightly in cloth.

Interestingly, archaeologist Carl Feagans, who was not involved in the new research but has previously published on the practice, points out that the procedure appears to have had no negative impact on subjects’ cognitive function.

"The skulls [anthropologists] are finding are fully functional adults,” Feagans told Vice’s Alexandra Ossola in an interview for a 2014 feature on cranial deformation. "You would think if there was any neurological damage done, the practice would die out."

Science Alert’s Starr reports that several of the Houtaomuga humans—in particular, the 3-year-old and the adult woman—were buried with opulent goods indicative of high status. A shared tomb containing an adult and child who both bore signs of cranial modification further suggests the practice could have been performed by certain families.

“All of this evidence indicates that among the whole population, the practice of intentional cranial modification was a type of cultural practice only implemented on certain individuals," the researchers write in the study. “Although the selective criterion and meaning of this cultural behavior are still unknown, the distinction of identity, perhaps depending on family affiliation or socioeconomic status, should be [principal] reasons for the cranial modification.”

Speaking with Bower, Xijun Ni, a paleoanthropologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences who was not involved in the latest research, says the oldest Houtaomuga skull, belonging to a 12,000-year-old adult male, was probably not intentionally modified. He argues that the cranial shape seen in the specimen is similar to that of some modern Asians, adding that the only “solid evidence” of cranial reshaping at the site dates to some 6,000 years ago. Study co-author Qian Wang, however, tells Bower that the extent of bone flattening seen on the man’s braincase exceeds any naturally occurring variations—a sentiment echoed by Maria Mednikova, an archaeologist at the Russian Academy of Sciences who was not involved in the study but deems the skull “intentionally remodeled.”

The researchers’ findings point toward skull reshaping’s prevalence across the ancient world. But as Wang cautions to the Daily Mail’s Victoria Bell, “It is too early to tell whether intentional cranial modification first emerged in East Asia and spread elsewhere or originated independently in different places.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)