Prehistoric Crocodiles Preferred Plants Over Prey

A study of croc teeth show many species during the time of the dinos were herbivores and omnivores, not strict meat eaters

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/d2/d4d25d36-e089-4ac9-a21d-b66934f7ec8a/istock-171336276.jpg)

Jagged-toothed, flesh-shredding crocodiles of the modern world had to beat out a lot of other tough species to survive a whopping 200 million years. They munched their way through history while Tyrannosaurus Rex, the megalodon and other toothy predators died out. But the crocodile family tree wasn't all cookie-cutter, zig-zagging pearly whites.

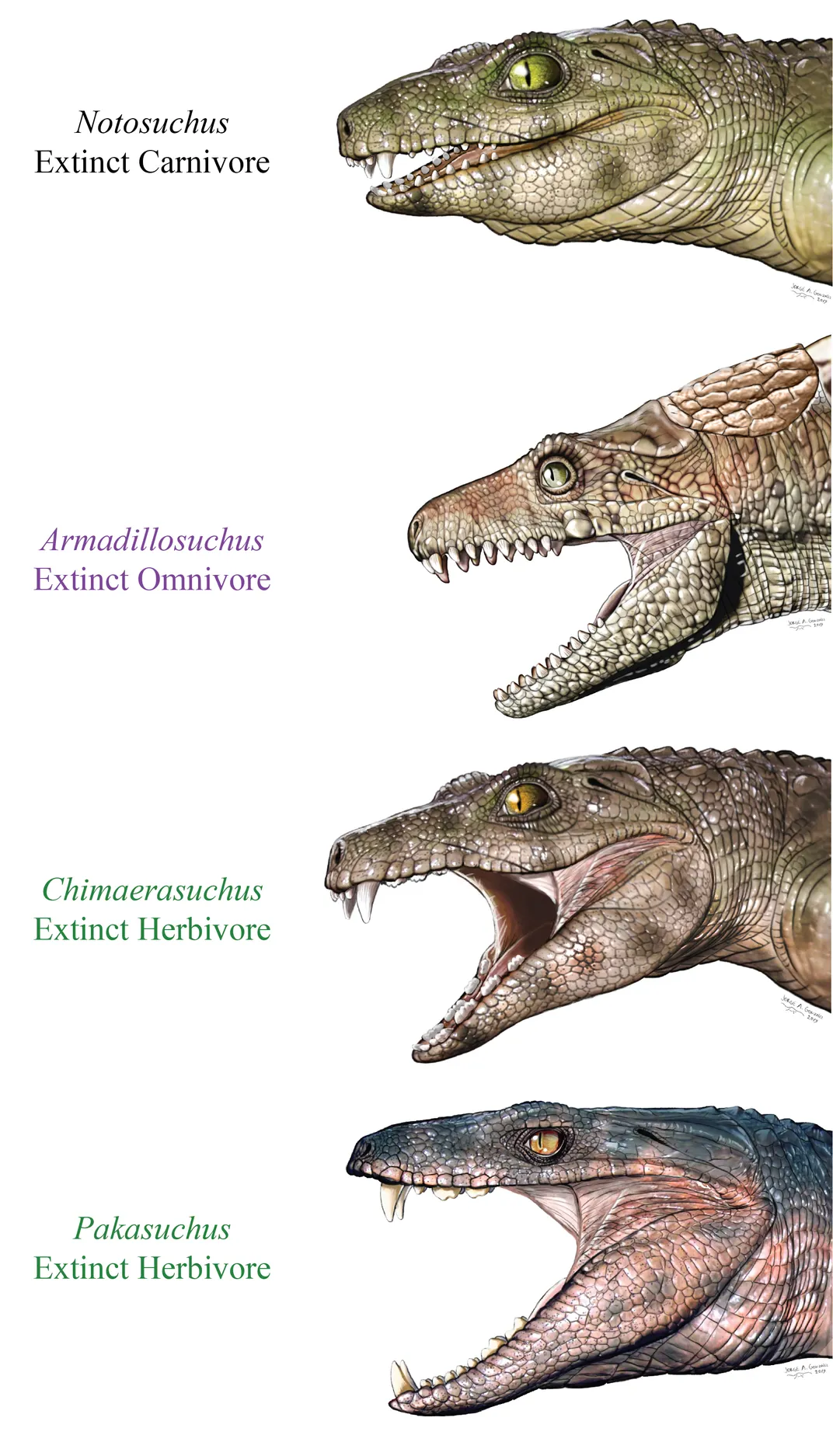

The dental tapestry of prehistoric crocodylians was much more diverse than it is today, according to a new study published in the journal Current Biology. For millions of years, many species of vegetarian and omnivorous crocs roamed the earth, but why pro-plant crocs died out while their carnivore cousins stood the test of time remains a mystery.

Researchers analyzed 146 fossil teeth belonging to 16 extinct crocodile species, using techniques previously developed to assess the function of mammal teeth, reports Tim Vernimmen at National Geographic. Keegan Melstrom and Randall Irmis, both researchers at the University of Utah, used computer modeling to quantify the complexity of each tooth, which provides clues to what type of materials it was designed to chew.

In general, the teeth of carnivores are pretty simple: they are sharp and pointy, like daggers. The teeth of herbivores and omnivores, however, are more complex with multiple surfaces used for grinding plant material.

“These teeth almost invariably belong to animals that feed on plants, the leafs, branches, and stems of which often require a lot of chewing before they can be digested,” Melstrom tells Vernimmen.

Their analysis revealed that half of the species examined were likely at least partially herbivorous, while some were probably insectivorous and others were strictly herbivores. The teeth show that plant-eating evolved independently in the crocs three times and perhaps as many as six times, reports Cara Giaimo at The New York Times.

The crocs appeared to specialize in different veggie diets as well. One species, Simosuchus, has teeth similar to modern marine iguanas, which graze on algae growing on seaside rocks. Other teeth are more square and likely helped the animals eat leaves, stems or other plant material. But since the teeth were very different from modern reptiles it's difficult to say exactly what their diets were, just that they were likely plant-based.

“Extinct crocs had weirder teeth than I ever could have possibly imagined,” Melstrom tells Zoe Kean at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

“Our work demonstrates that extinct crocodyliforms had an incredibly varied diet,” Melstrom says in a press release. “Some were similar to living crocodylians and were primarily carnivorous, others were omnivores and still others likely specialized in plants. The herbivores lived on different continents at different times, some alongside mammals and mammal relatives, and others did not. This suggests that an herbivorous crocodyliform was successful in a variety of environments.”

But they weren’t successful enough: Early plant-gobbling crocs evolved soon after the End-Triassic Mass Extinction some 200 million years ago and then disappeared during the Cretaceous Mass Extinction, 66 million years ago, when 80 percent of all animals species, including the dinosaurs, died off. The only crocs to survive that apocalypse are the ancestors of the sharp-toothed, meat-eaters we know today.

The findings change what we know about ecology in the dinosaur era. Previously, reports Kean, researchers believed that crocodylians were always near the top of the food chain. It was believed that if crocs did evolve herbivory, it would be in the absence of competition from ancient mammals.

But this challenges those ideas, says ancient crocodile expert Paul Willis of Flinders University, not involved in the study. “There are [ancient] crocodiles that would have taken down Tyrannosaurus without a problem,” he says. “What you’ve got here is crocodyliforms that are actually at the bottom of the food chain.”

The new study suggests crocs of all shapes and sizes occupied ecological niches alongside mammals and other herbivores. Next, the team hopes to continue to study more fossil teeth. They also want to figure out why the diversity of crocodylian species exploded after the first mass extinction, but then after the following extinction event, the lineage was restricted to the meat-eating, semi-aquatic reptiles that haunt lakes and rivers to this day.