Ancient Egyptian Head Cones Were Real, Grave Excavations Suggest

Once relegated to wall paintings, the curious headpieces have finally been found in physical form, but archaeologists remain unsure of their purpose

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/2c/7c2c0d00-7fdf-4fce-ac53-1d408c3aa12f/amarna_3.jpg)

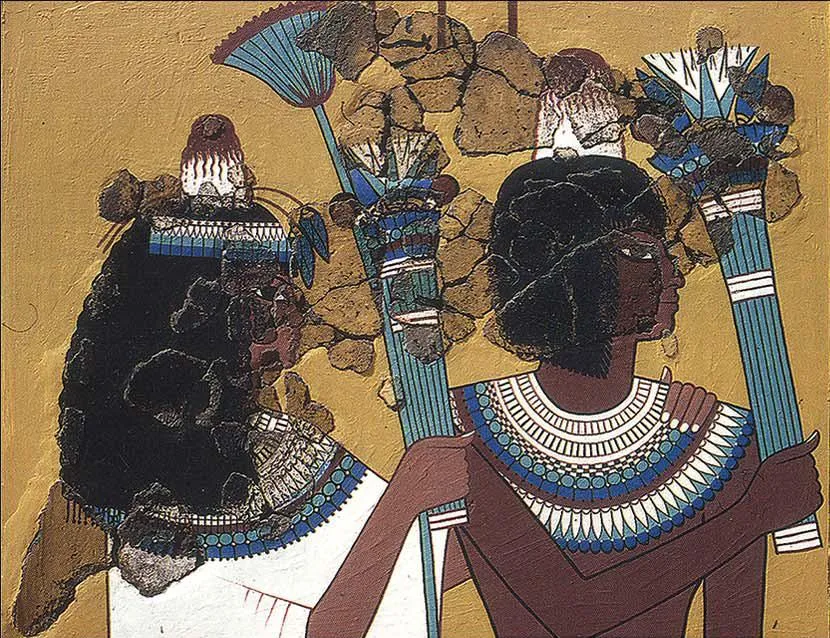

The ancient Egyptians were known for their spectacular headwear, from double crowns worn by pharaohs to the striped nemes headcloths immortalized by Tutankhamun’s golden death mask. But some of the items worn by the ancients have long defied explanation. Take, for instance, head cones: mysterious, elongated domes found adorning the heads of prominent figures in an array of 3,550- to 2,000-year-old works of art.

Archaeologists batted theories back and forth for years, speculating on the purpose of these curious cones. Some contended they were scented lumps of ointment designed to be melted, then used to cleanse and perfume the body. Others insisted the cones were part of a burial ritual, entombed with their wearers to confer fortune or fertility in the afterlife. And many doubted whether the cones were real at all: Perhaps, they argued, the cones were restricted to the two-dimensional realm of wall paintings—pure artistic symbolism denoting special status like halos in Christian art, as Colin Barras writes for Science magazine.

Now, after years of doubt, the naysayers have (probably) been proven wrong. Reporting yesterday in the journal Antiquity, a team led by Anna Stevens of Australia’s Monash University unearthed two real-life head cones in graves at the archaeological site of Amarna, Egypt. Head cones, it appears, did exist—and, at least in some cases, they joined their wearers in death.

Around 1300 B.C., Amarna was home to the city of Akhenaten, eponymously named by its pharaoh. Nowadays, archaeologists prize Akhenaten for its artifacts—including those recovered from the thousands of graves that dot its landscape, all dug and occupied within a period of roughly 15 years.

Among the buried, Stevens and her team discovered two individuals sporting full heads of hair, as well as hollow, cream-colored head cones. Both cones were about three inches tall and riddled with holes where insects had bored through their beeswax-like base material post-interment. The cones’ wearers, who had endured bouts of grave robbing, were also in bad shape, but there was enough left for the researchers to identify one of the individuals as a woman who died in her twenties and the other as a person of indeterminate sex who died between the ages of 15 and 20.

Both cone-wearers were entombed in low-status graves in a worker’s cemetery—a fact that came as a bit of a surprise, Stevens tells Bruce Bower at Science News. But given the headpieces’ elusive nature, she says, “The most surprising thing is that these objects turned up at all.”

After a few thousand years underground, the cones (and their wearers) no longer had much to say about their original purpose. But Stevens and her team tentatively propose that the headpieces were spiritual, intended to guide or empower individuals as they transitioned to the afterlife. Because there’s no evidence that the wax was melted or dribbled onto the body or hair, they researchers say the cones probably weren’t used as ointments.

But other experts who weren’t involved in the study are hesitant to rule out alternative explanations. Speaking with Science magazine’s Barras, Lise Manniche, an archaeologist at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, points out that the cones aren’t consistent with most artwork, which generally shows them perched on people of status.

“I would interpret the two cones as ‘dummy cones,’ used by less fortunate inhabitants in the city as a substitute for the … cones of the middle and upper classes,” Manniche explains to Live Science’s Owen Jarus. “By using these dummies, they would have hoped to narrow the social gap in the next life.”

If that’s the case, the bona fide cones of the elite—should they exist—remain mysterious.

Rune Nyord, an archaeologist at Emory University, tells Barras that artwork suggests cones were worn by living Egyptians, too. Numerous depictions feature the head gear at festive banquets, or award ceremonies conducted before the pharaoh. In a way, the versatility makes sense: Afterlife or not, you don’t have to be dead to don a jaunty hat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)