Andrew Jackson Wasn’t Always on the $20 Bill

The controversial president’s face has only been on $20 bills since 1928

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/15/451505a6-69e4-461c-a95a-5ef598b72d62/us-10-frn-1914-fr-919a.jpg)

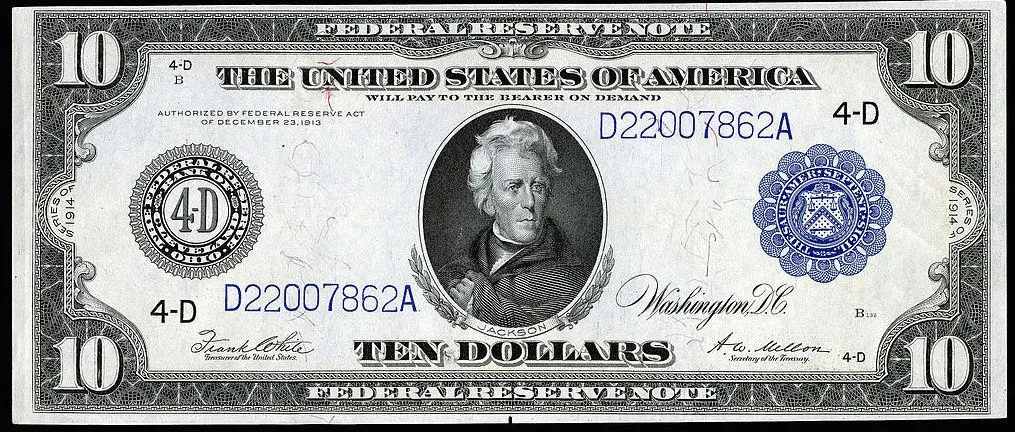

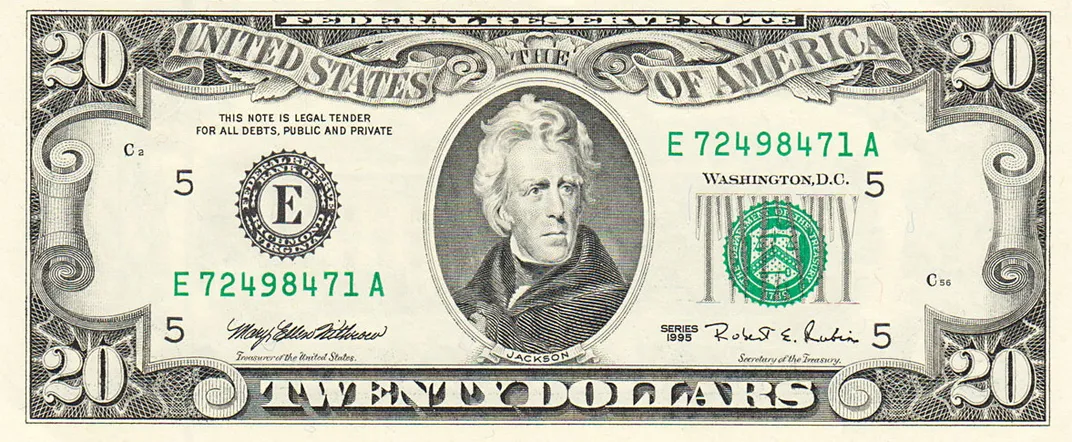

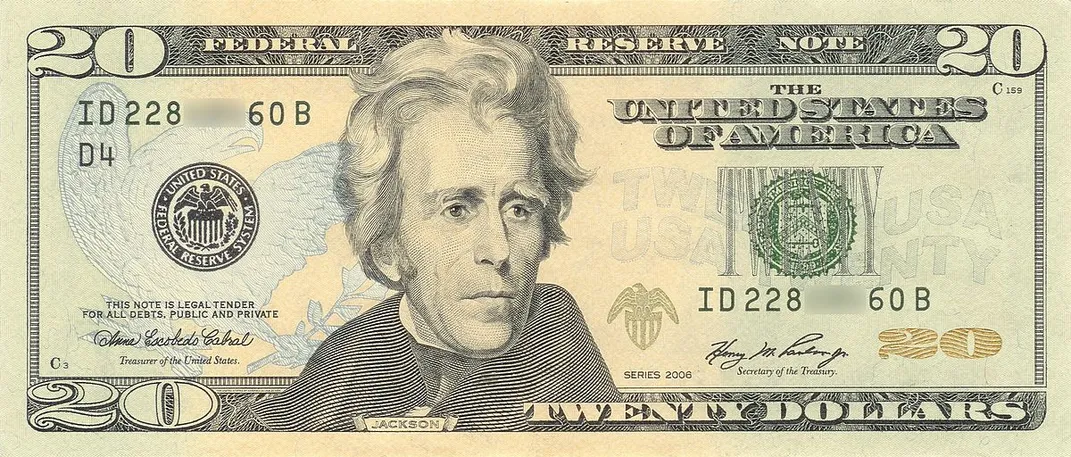

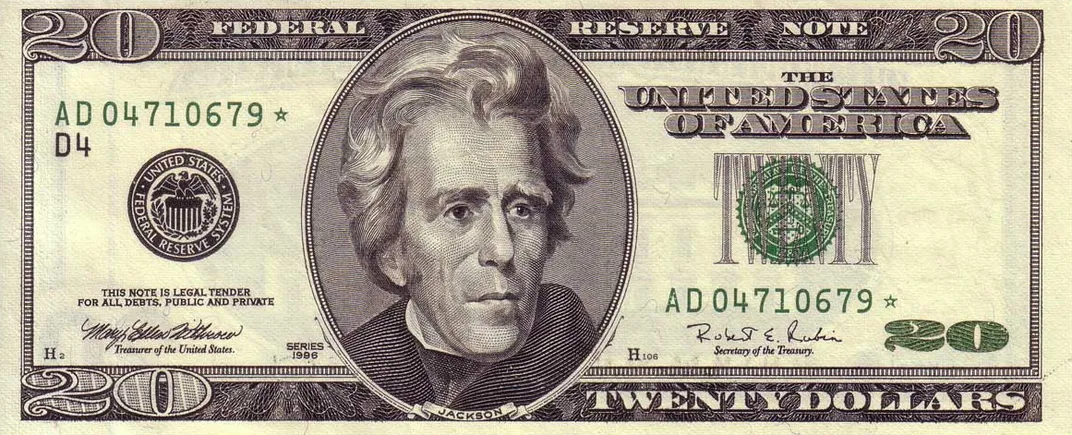

When it comes to the the seventh president of the United States and currency, the ubiquitous $20 bill comes immediately to mind. After all, it’s Andrew Jackson’s best-known portrait in popular culture: an intense man with over-the-top collar, windswept hair and a look of fierce determination in his engraved eyes. But Jackson wasn’t always king of the twenty: in fact, he got his start on the $10 bill instead.

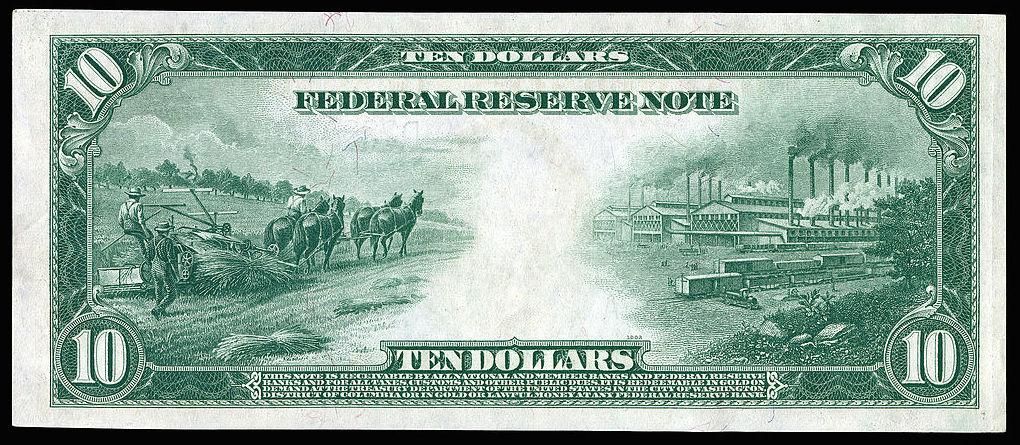

Before the Federal Reserve got authority to issue bills, bank notes were printed by the National Banking System, which was susceptible to bank runs and financial panics. To stabilize the system, the government created the Federal Reserve System and redesigned national currency. That was in 1914, and on those first Federal Reserve Notes, Jackson made his debut on the $10.

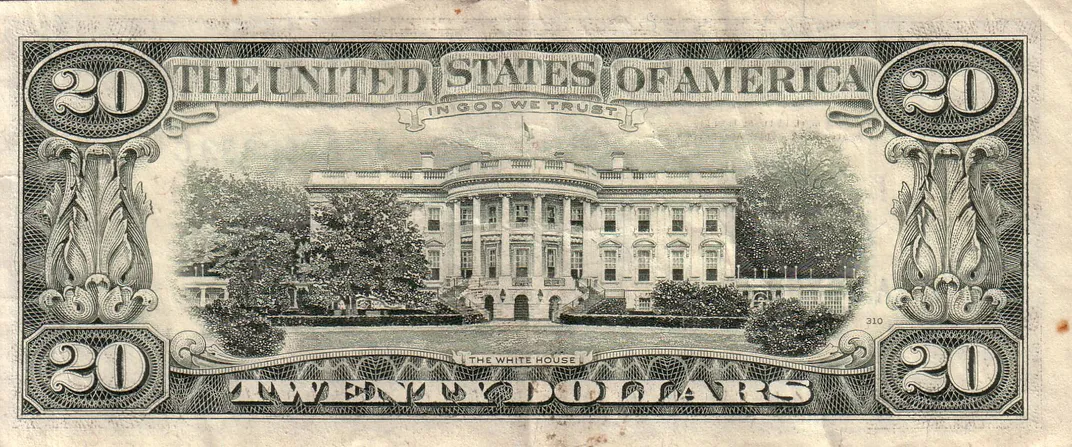

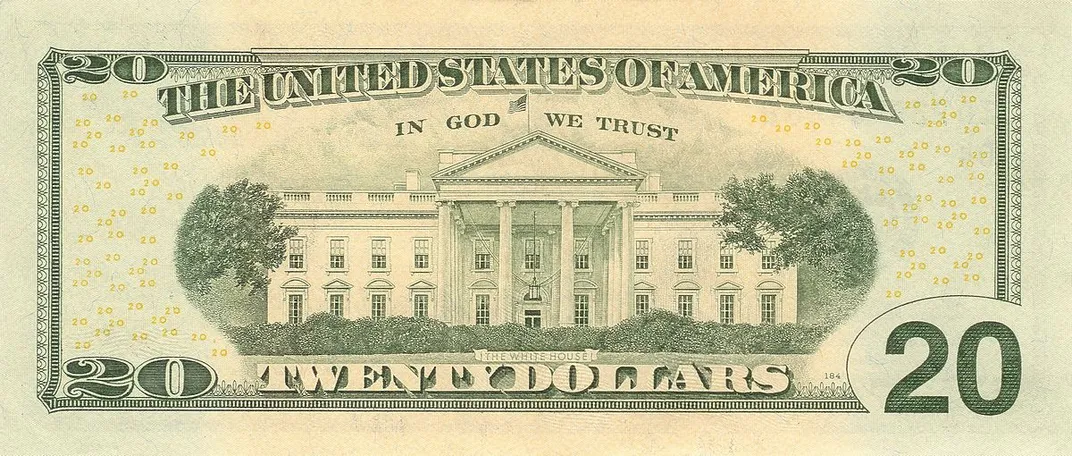

In 1928, the green busts got reshuffled. Jackson got an upgrade to the $20, and Cleveland, who was on the $20, got bumped all the way up to the $1000. Hamilton, who had been the face of the $1000, got a downgrade to the $10, where he's been since. That same year, bills were cut down in size to the size they are now: 2.61 inches wide and 6.14 inches long.

Over the years, the choice to feature Jackson on federal currency at all has become controversial, due to his policies while in office, which included the brutal removal of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands. Commentators like Slate’s Jillian Keenan have called for his removal from the $20, arguing that “Andrew Jackson engineered a genocide. He shouldn’t be on our currency.”

Those cries are increasing in number with the announcement that the next $10 bill will feature a woman. The Washington Post’s Steven Mufson calls the decision to push aside Hamilton in favor of a woman on the $10 bill instead of replacing Jackson on the $20 bill a “grave historical injustice.”

And perhaps removing him from the bill would be the right way to honor Jackson after all. The President didn’t even like paper money, notes Mufson. In fact, Jackson didn’t really like banks, either: he famously called the delegation of bankers discussing the charter of the Second Bank of the United States “a den of vipers and thieves” and was suspicious of the soundness of paper money as opposed to gold and silver.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)