Archaeologists Mine Medieval Toilets for Traces of Gut Microbiomes

New techniques could help researchers understand human diets in different times and places

:focal(384x289:385x290)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10/c7/10c7ace0-aae2-4205-8b07-fd5fae07c807/shit.jpg)

Centuries-old cesspits can be veritable treasure troves for archaeologists, offering insights on historical humans’ diet, health and habits. Now, reports Kiona N. Smith for Ars Technica, an analysis of two such latrines in Latvia and Israel suggests the individuals who used them had intestinal microbiomes unlike those of either hunter-gatherers or modern industrialized people.

The researchers, who published their findings in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, examined a 14th-century cesspit in Riga and a 15th-century one in Jerusalem. When the waste pits were in use, the areas were urban but not industrialized, meaning their residents probably ate and digested food differently than the city dwellers of today.

As Hannah Brown explains for the Jerusalem Post, gut microbiomes encompass all of the microbes found in the intestines, including bacteria, viruses and fungi. By studying medieval microbial communities, scientists can track changes in diet and digestion over time and better contextualize the health of modern microbiomes.

“We felt the medieval period was sufficiently old for us to detect change compared with modern populations, but not so old that the DNA would not survive well enough to undertake the study,” study co-author Piers Mitchell, an archaeologist at Cambridge University, tells Ars Technica. “We chose the two sites in Jerusalem and Riga as they were both from the same time period but from different geographic regions, which might lead to different microbiomes in those populations.”

The scientists’ investigation confirmed their suspicions, revealing DNA remnants from Treponema bacteria, which are found in the guts of modern hunter-gatherers but not industrialized people, and Bifidobacterium, which are present in industrialized people but not hunter-gatherers. Per the paper, researchers often describe these differences in microbiomes as the result of a dietary trade-off.

“We don’t know of a modern source that harbors the microbial content we see here,” says co-lead author Susanna Sabin, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, in a statement.

The team can’t be certain whether individuals in the medieval cities actually harbored both bacterial strains. According to Ars Technica, the Jerusalem samples came from a cesspit that held the contents of at least two households’ toilets; the Riga samples were from a public latrine used by many people. The presence of both types of bacteria could reflect diversity among city residents, or indicate that these medieval humans possessed microbiomes unlike any known today.

Sabin, Mitchell and their colleagues detected the centuries-old microbes with the help of a technique previously used to study epidemics, reports Cosmos magazine.

“At the outset we weren’t sure if molecular signatures of gut contents would survive in the latrines over hundreds of years,” says co-lead author Kirsten Bos, also of the Max Planck Institute, in the statement. “Many of our successes in ancient bacterial retrieval thus far have come from calcified tissues like bones and dental calculus, which offer very different preservation conditions.”

To analyze the latrines’ contents, the researchers first had to distinguish the gut microbes from those normally found in the surrounding soil. Upon completing this task, they found evidence of a range of organisms, including bacteria, archaea, protozoa, parasitic worms and fungi.

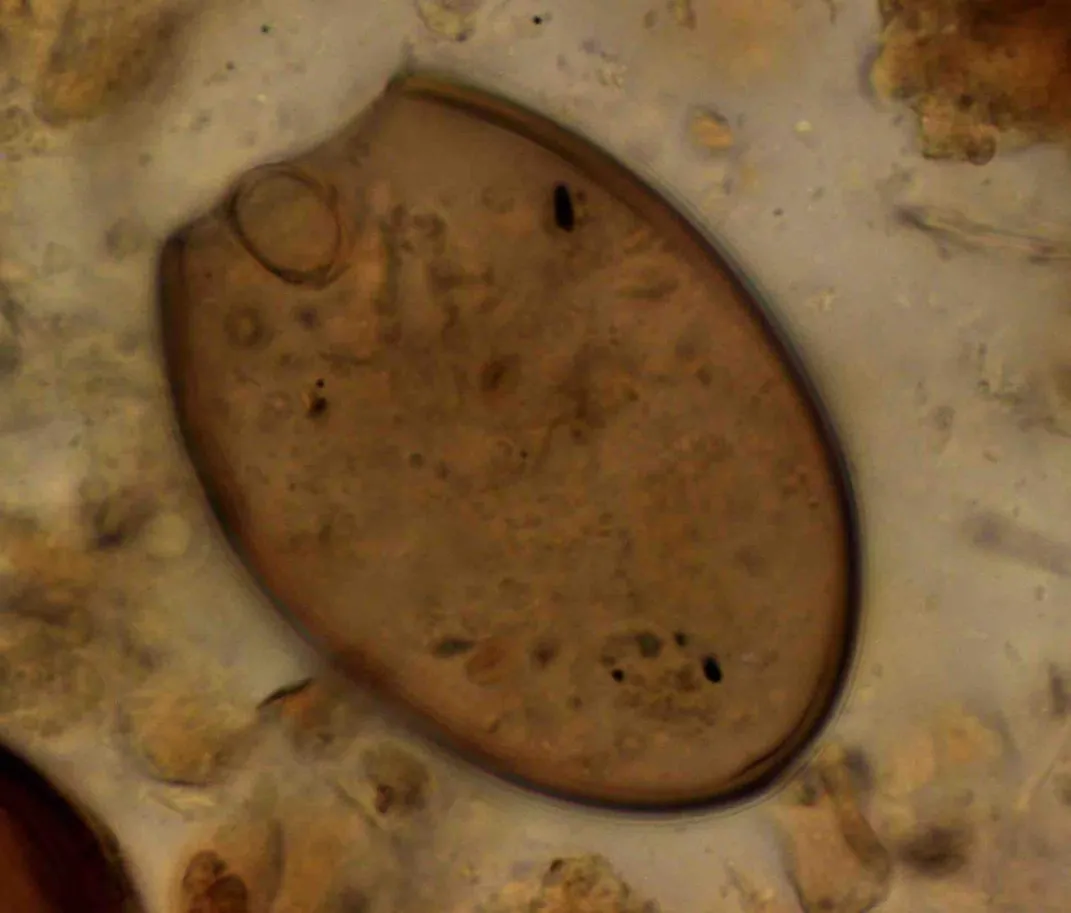

Cesspits, which often contain discarded objects and remnants of human waste, provide a wealth of information for archaeologists. Previous studies of the contents of old latrines have found remains such as parasite eggs that can be examined with a microscope—but many of the organisms examined in the new research were much too small for that technique. Using metagenomics, or the study of microorganisms through DNA extraction, scientists can glean additional information.

The study’s authors hope the techniques outlined in the paper will help researchers analyze gut biomes from other times and places, providing more clarity about changes in historical diets.

“If we are to determine what constitutes a healthy microbiome for modern people,” says Mitchell in the statement, “we should start looking at the microbiomes of our ancestors who lived before antibiotic use, fast food, and the other trappings of industrialization.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)