Why Are These Medieval-Era Skulls Found in Gabon Missing Their Front Teeth?

Intact, 500-year-old upper jaws discovered in an African cave bear evidence of deliberate facial modification

:focal(419x304:420x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/95/a195593f-407a-4e54-83ac-fbe2ab827409/modified_skulls.jpg)

Archaeologists exploring a subterranean cave in Gabon have discovered the skulls of medieval-era adults who altered their appearance by removing their front teeth.

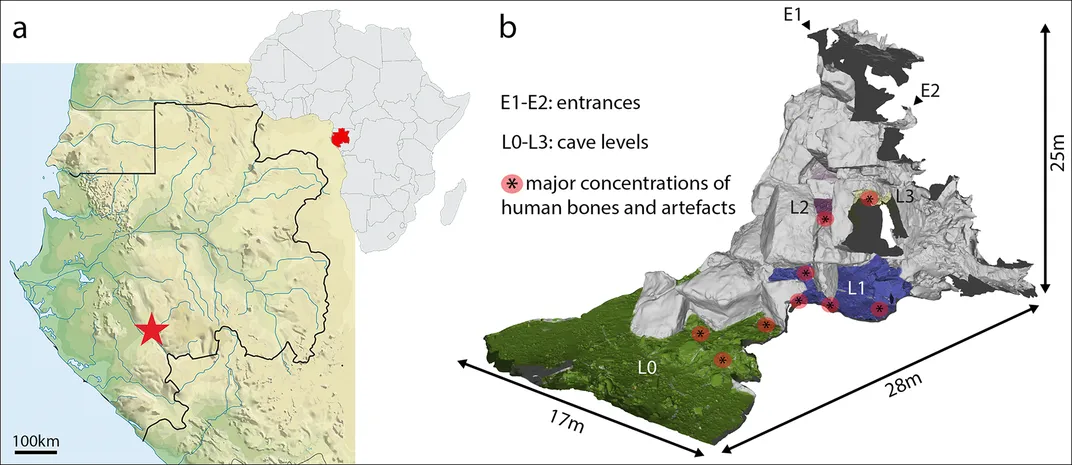

As Mindy Weisberger reports for Live Science, a joint French and Gabonese research team working at Iroungou, a cave in the Ngounié province of the West Central African country, unearthed the skeletons of at least 28 people (including 24 adults and 4 children) who lived during the 14th and 15th centuries. The group’s findings are newly published in the journal Antiquity.

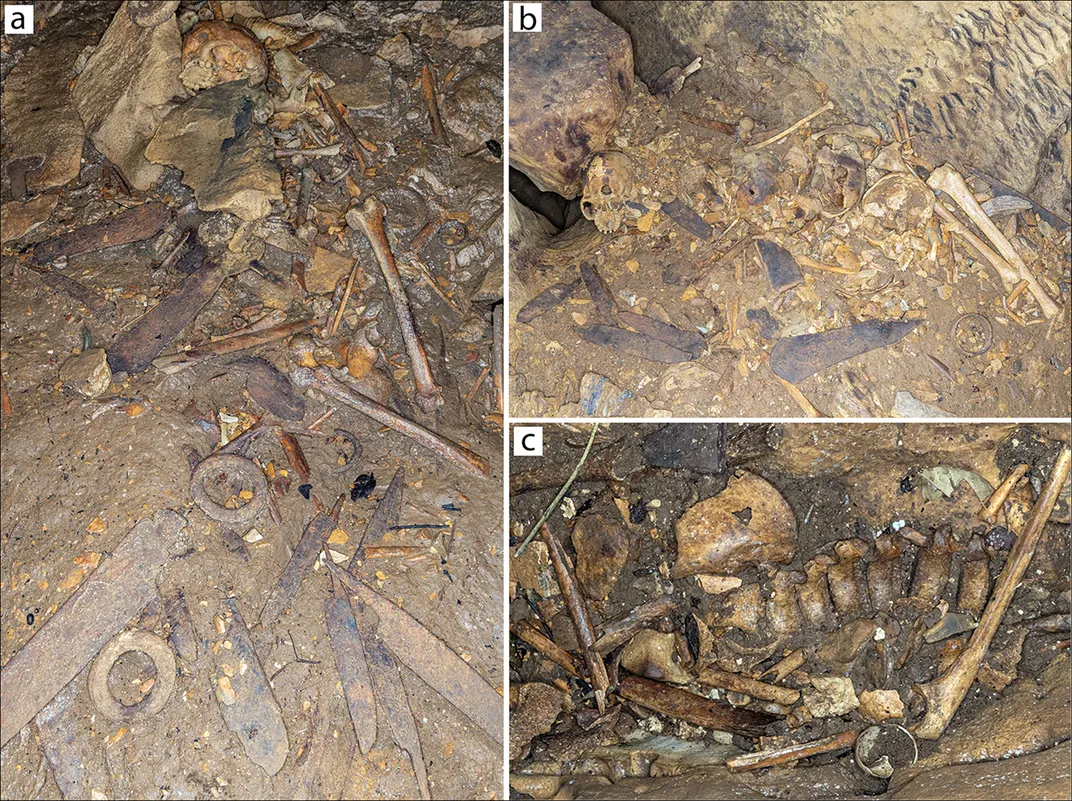

Though Richard Oslisly, an archaeologist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris, initially uncovered the cave in 1992, he and his team only investigated the inaccessible site in 2018. During this more recent expedition, researchers found human remains, metal tools, weapons and pieces of jewelry.

“There are very few sites with archaeological human remains for this region,” lead author Sébastien Villotte, a researcher at CNRS, tells Live Science. “The fact that children, teenagers, adult males and females were buried here, with so many artifacts—more than 500!—was astonishing.”

Experts from Gabon’s Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux (ANPN) used a cavity in the cave’s roof to access the burials. Per Heritage Daily, the team speculates that the region’s inhabitants “lowered, or dropped,” the deceased through that very same hole. According to the study, the cavern reaches a maximum depth of around 82 feet.

Highlights of the find include bracelets and rings; knives, axes and hoes made out of local iron and imported copper; 127 Atlantic marine shells; and 39 pierced carnivore teeth. Given the rich nature of these funerary artifacts, the scholars speculate that the people buried in the cave were of a high socioeconomic status, notes Live Science.

All of the intact upper jaws recovered from the site were missing their four front teeth, also known as central and lateral permanent incisors. The tooth sockets showed signs of healing, suggesting the teeth were removed when their owners were still alive.

“Intentional dental modification has a long history in Africa, but the extraction of the upper four incisors is a relatively rare form,” Villotte tells David Ruiz Marull of Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia, per Google Translate.

Such drastic body modifications would have altered the subject’s facial structure and impacted how they pronounced words, reports La Vanguardia. The team posits that individuals who underwent the process viewed it as an indicator of their social status or membership in a specific group.

According to the study, scholars have “repeatedly observed” dental modifications ranging from fillings to chippings to removals in the skeletal remains of African people, including enslaved individuals buried outside the continent. But the specific form observed at Iroungou is uncommon, with documentation limited to reports by 19th- and early 20th-century ethnographers working in the region.

In a 2017 essay, Joel D. Irish of Liverpool John Moores University wrote that dental modification in sub-Saharan Africa often led to “oral trauma … ranging from mild to life threatening.” But the practice’s intended results—including “perceived and plausible benefits to individual reproductive fitness” and prevention or treatment of disease—were thought to outweigh such risks, he added.

Speaking with Live Science, Villotte says, “Many various reasons are advocated for tooth removal by the people who practiced it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)