An Archive of Fugitive Slave Ads Sheds New Light on Lost Histories

Wanted ads posted by slave owners reveal details of life under slavery

:focal(495x290:496x291)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/88/78884aa5-b5d4-4182-98a1-7de75ecb45d9/archivephoto1.jpg)

For hundreds of years, some of the best sources of information about life under slavery in the United States came from autobiographies published by former slaves. From Frederick Douglass to Solomon Northup, these narratives shed light on the horrors and atrocities suffered by millions of people with mundane regularity. But while their stories are important in documenting the history of slavery, they represent just a miniscule fraction of the people who were enslaved in the U.S. Now, a group of historians are working on compiling an archive of biographical information of many slaves gleaned from a strange source: fugitive slave ads.

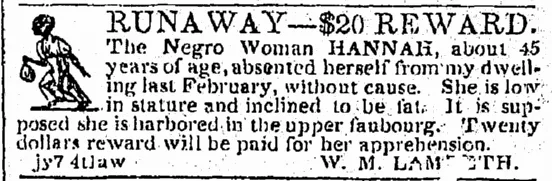

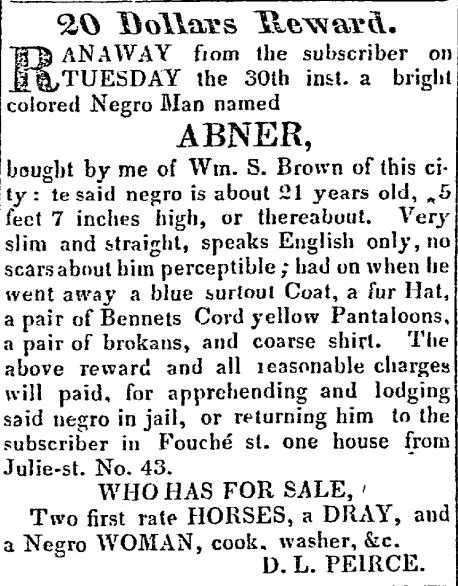

Fugitive slave ads are an ironic source of details about the lives of slaves who might otherwise be lost to history. When slaves managed to escape their captors, slave owners would often publish ads in the classifieds sections of newspapers all throughout the country offering a reward for the runaway’s recapture and return. Even George Washington took out an advertisment to recapture one of his slaves. Ironically, these ads have become an important resource for historians trying to learn more about the lives of slaves who they would otherwise know nothing about.

“They wanted to provide as much detail about their appearance, their life story, how they carried themselves, what they were wearing,” Joshua Rothman, a historian at the University of Alabama, tells Smithsonian.com. “Each one of these things is sort of a little biography.”

For decades, historians have looked to wanted ads posted by slave owners to glean details and insights into the lives of slaves that might not have been available elsewhere. While the level of detail varies from ad to ad, in many cases the slave owners would publish all sorts of descriptions and personal details about the escaped slaves, such as if they might have been headed for another plantation where they had family, or if they took their children with them when they ran. Now, Rothman and a small collective of colleagues are trying to compile as many of them as they can in one archive that they call Freedom on the Move.

“These ads are, in a sense, the Tweets of the 'master class,'” Ed Baptist, a historian at Cornell University who is working on the archive tells Smithsonian.com. “They’re short, in certain ways they’re formulaic, but if you get enough of them together they can really tell you something about what’s going on.”

The volume of these ads coupled with the fact that they have so far been scattered in collections around the country makes them hard to survey on a large scale. By gathering as many ads as they can in one searchable archive, these historians hope that they will be able to uncover new trends and paint a fuller picture of the lives of slaves pursuing their freedom, says Mary Mitchell, a historian at the University of New Orleans who is collaborating with Baptist and Rothman on “Freedom on the Move.”

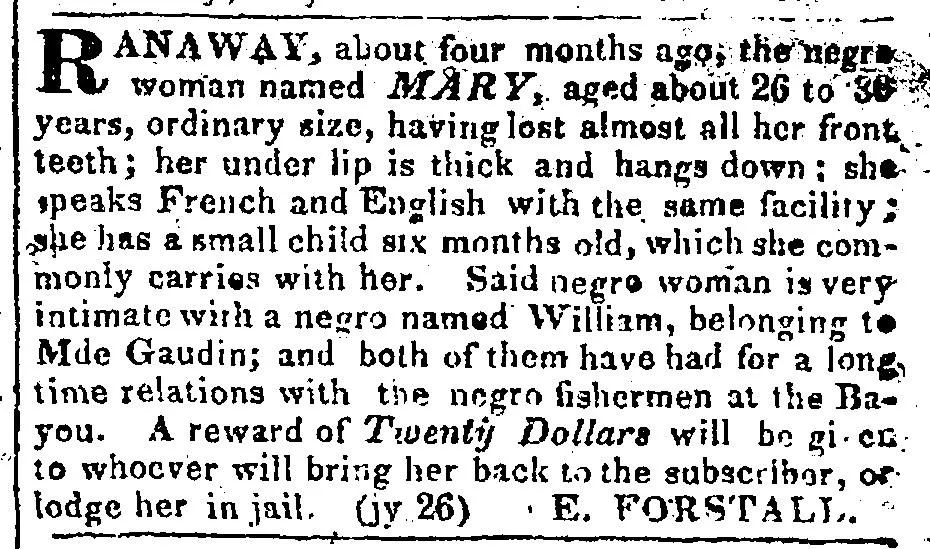

“Most of the very familiar narratives of people running away and making it to freedom are men,” Mitchell says. “But we see a lot of women. And then once we finally pull them all together and are finally able to count, it’s going to be great to see those numbers. It’s something that we haven’t really seen and studied up close to know.”

By comparing these ads on a larger scale, Mitchell hopes that they will be able to see patterns in the stories of escaped slaves, like what times of year most people fled, or whether waves of escapes correlated with political events and economic trends. The archive is still a work in progress, and Mitchell and her colleagues have been reaching out to other researcher and educators for help transcribing the tens of thousands of ads they have already collected. They hope that in the future the archive will become a resource for researchers looking to study the movement of escaped slaves across the U.S. as well as for teachers who want to show their students another side of the story of slavery in America.

“It tells us a different story about resistance than resistance on the plantation or the Underground Railroad type of resistance,” Mitchell says. “There is this other kind of resistance that is this constant, steady irritation to the slave regime. And the more ads we find, the more constant it clearly was.”