Arlington National Cemetery Opens Its 105-Year-Old Time Capsule

The trove of artifacts, hidden in a cornerstone in 1915, is now available to explore online

:focal(1033x438:1034x439)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c6/13/c61370de-6944-4219-8dc3-af3e7bab0c23/2020_may19_timecapsule.jpg)

On October 13, 1915, President Woodrow Wilson spread the mortar for the cornerstone of the Arlington Cemetery Memorial Amphitheater. Unlike most cornerstones, this foundational rock was hollow: Hidden within was a copper box filled with items emblematic of American life in the year construction began.

Scheduled for completion by 1917, the amphitheater actually took nearly five years to complete. Now, on the centennial of the space’s dedication, conservators have finally revealed the 105-year-old time capsule’s contents, reports Michael Ruane for the Washington Post.

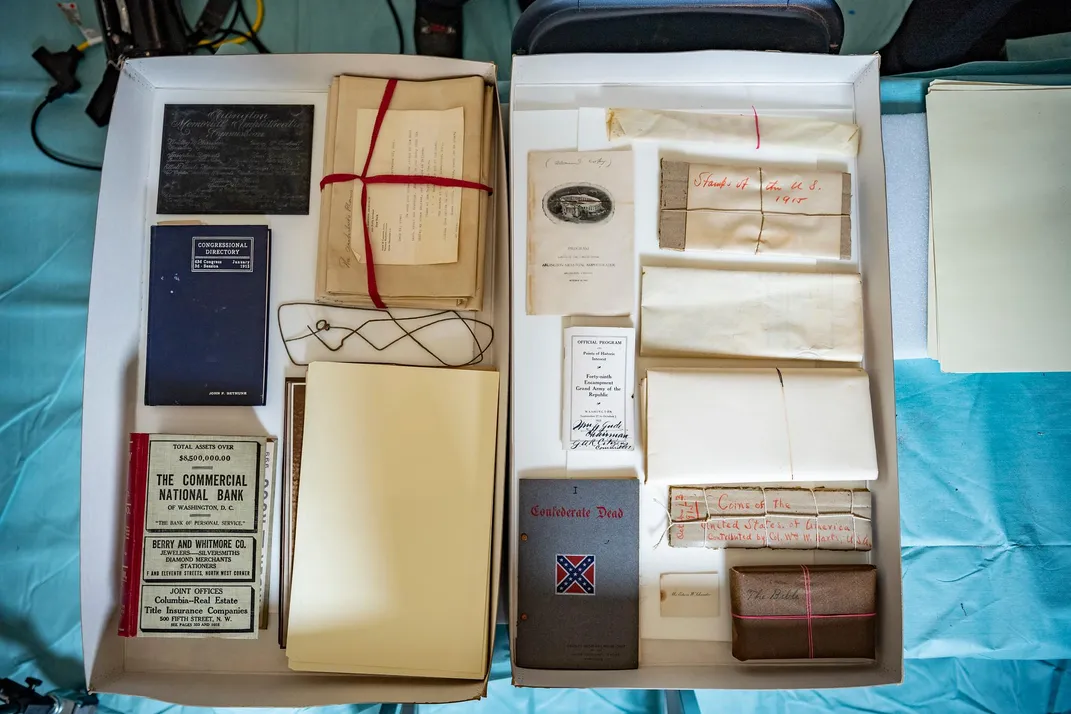

Per a statement, artifacts found in the box include copies of the Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution, an American flag, coins, stamps, a map of Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s design for Washington D.C., and an autographed photograph of Wilson himself. The time capsule also held four local newspapers, a Bible, documents bound in red tape and a pamphlet titled “Confederate Dead,” according to the Post.

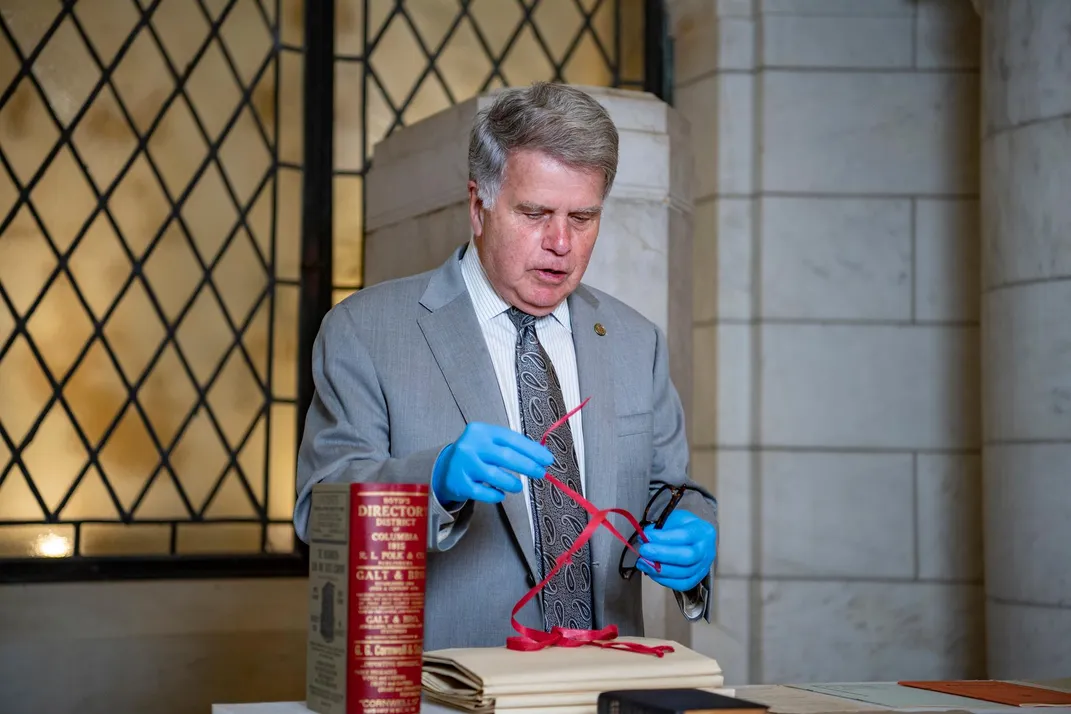

“One of my favorite things I was so excited to see is this wonderful example of red tape,” says Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero in the statement. “All of the records in the National Archives, when they were moved into that building, were carefully protected with wrappings that were held together with this red tape. This is where the saying comes [from] about cutting through the red tape. It is actually—literally—the red tape.”

The amphitheater’s original cornerstone—as well as the time capsule housed within—was removed during construction in 1974. Temporarily stored at the National Archives, the box was only reinstalled in the 1990s. As the Post notes, workers tasked with placing the new cornerstone evidently decided to add their own mementos to the trove, tucking a peanut butter jar filled with notes and business cards beside the 1915 capsule.

“It was sort of a rush job,” conservator Caitlin Smith tells the Post. “But you can understand the impulse to add your name to history.”

Safely retrieving the 20th-century artifacts proved to be a daunting task. As Thomas Brading reports for the U.S. Army News Service, staff spent several weeks removing, cleaning, evaluating and finally opening the copper box.

Arlington National Cemetery is currently closed due to COVID-19, but thanks to a virtual exhibition—the site’s first, according to the U.S. Army News Service—history lovers can explore the time capsule’s contents from home.

In the statement, Ferriero points out that time capsules, or memorabilia boxes, are an American invention.

“The concept is to celebrate construction of a new institution, a new building, an important new building, by providing an opportunity to share what life was like at that particular time in our history,” he says.

Arlington National Cemetery served as a site of reconciliation after the Civil War. In 1873, reports Alice Swan for Avenue News, the James R. Tanner Amphitheater was built to host Decoration Day events, which found families of Civil War veterans decorating their loved ones’ graves. The larger marble amphitheater followed some 50 years later, when crowds gathering for Decoration Day could no longer fit into the original space.

The world changed dramatically in the five years between the amphitheater’s cornerstone laying and its dedication. In 1915, the U.S. Constitution had just 17 amendments, but by the end of 1920, lawmakers had passed additional legislation prohibiting alcohol sales and guaranteeing women the right to vote. Curiously, the American flag found in the time capsule boasts just 46 stars, though the nation was then made up of 48 states. Arizona and New Mexico both joined the U.S. in 1912; Alaska and Hawaii entered the union as its 49th and 50th states, respectively, in 1959.

Other major events of the period include World War I, which the U.S. joined in 1917, and the 1918 influenza pandemic. The logistical challenge of getting all of the marble for the amphitheater’s exterior to Arlington, as well as completing construction while many young men were fighting in the war, contributed to delays in its completion.

“It was very exciting to open the time capsule, to see things that had not been seen in 105 years,” says Smith in a video of the box’s opening.

To the Washington Post, she adds, “It was meant to be opened. That’s why we put time capsules in place, for future generations to remember us by. We hope we’ve done something significant enough that it will be remembered … and we won’t be forgotten.”