Art Institute of Chicago Now Offers Open Access to 44,313 Images (and Counting)

Now you can view the museum’s masterpieces without taking a flight to Chicago

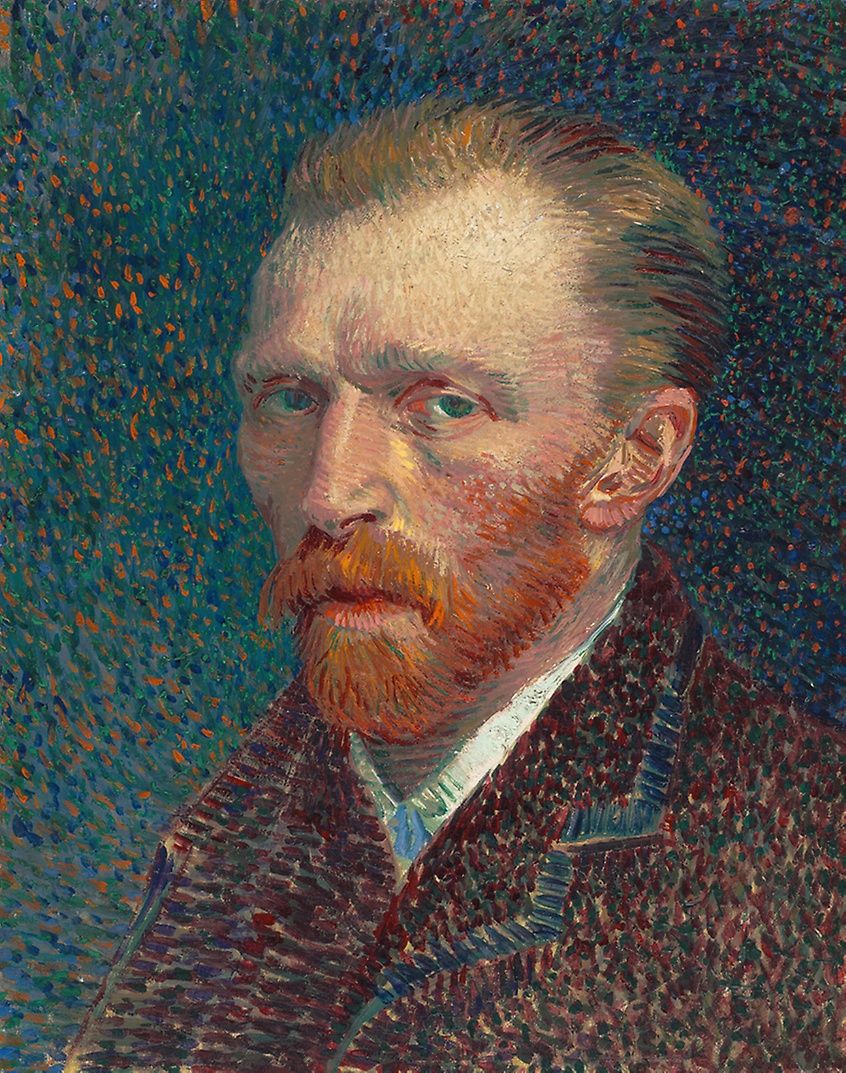

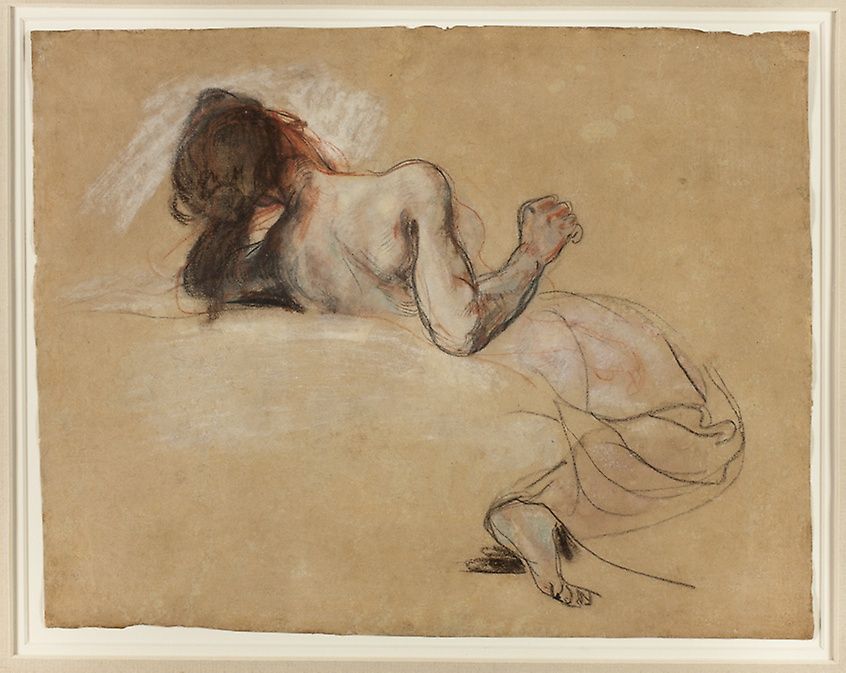

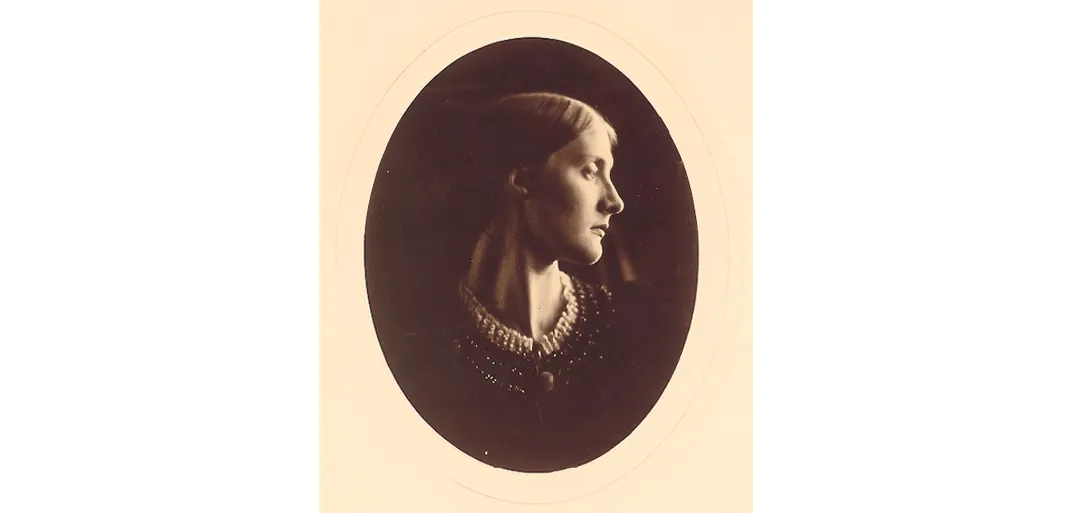

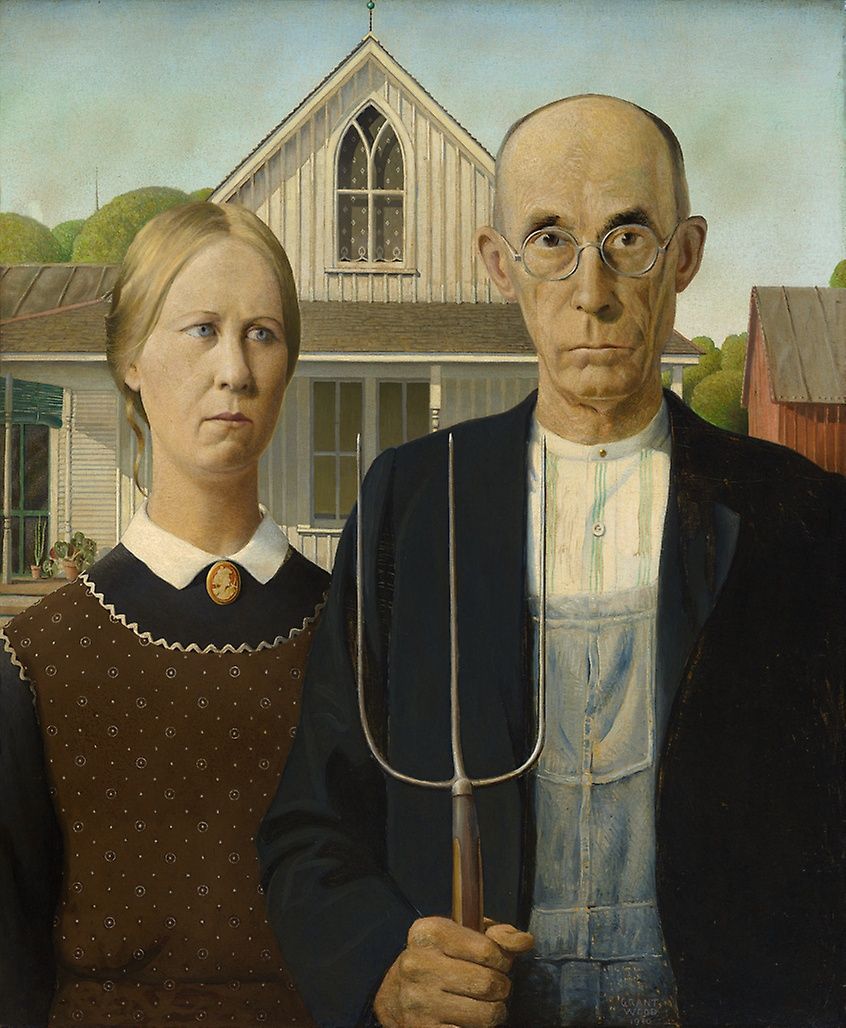

The Art Institute of Chicago boasts a collection of nearly 300,000 works of art, including some of the world’s most beloved paintings and sculptures. Edward Hopper’s 1942 “Nighthawks” infuses an otherwise melancholic night with the fluorescent glow of an all-night diner inhabited by four solitary figures. Grant Wood’s 1930 “American Gothic” captures the resilience of the nation’s rural Midwest. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Beata Beatrix”—an 1871 or ‘72 rendering of Dante Alighieri’s great love—achieves heights of emotions assisted by the pre-Raphaelite painter’s own sense of loss over the recent death of his wife and muse, Elizabeth Siddal. And the list goes on.

But if a trip to Chicago isn’t on the agenda, there’s another way to see these and other highlights from the museum’s vast collection: As Eileen Kinsella writes for artnet News, the Art Institute is the latest cultural powerhouse to offer open access to its digital archives, which total a staggering 44,313 images and counting.

According to a blog post written by Michael Neault, the museum’s executive creative director, the pictures are listed under a Creative Commons Zero, or CC0, license, which essentially amounts to no copyright restrictions whatsoever. Kinsella notes that the Art Institute has also upped the quality of images included in its database, enabling art lovers to zoom in and take a closer look at their favorites.

“Check out the paint strokes in Van Gogh’s ‘The Bedroom,’” Neault suggests, “the charcoal details on Charles White’s Harvest Talk,’ or the synaesthetic richness of Georgia O’Keeffe’s ‘Blue and Green Music.’”

The enhanced viewing capabilities and newfound open access are elements of a complete website overhaul, Deena ElGenaidi reports for Hyperallergic. The redesign also features a revamped search tool ideal for researchers and those hoping to locate works from a specific artist, movement or time period.

Edinburgh-based art historian Bendor Grosvenor, an ardent advocate of abolishing costly museum image fees, lauded the initiative in a post published on his Art History News blog. As he points out, cultural institutions across the United Kingdom—particularly London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, better known as the V&A—have been reluctant to take similar steps, citing their mandated free admission as justification for maintaining copyright fees.

The Art Institute charges a mandatory admission fee (Chicago residents can purchase a general admission ticket for $20, while out-of-staters have to shell out $25). So do Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, home of Rembrandt’s monumental “Night Watch,” and New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, both of which offer open access to their collections. It's worth noting, however, that the two museums do not charge visitors who meet certain conditions (at the Met, for example, proof of in-state residency brings admission down to pay what you will).

But institutions that charge for admission aren’t the only ones to place their archives in the public domain: In September, the fee-free National Museum of Sweden made 6,000 high-resolution reproductions of its historic works freely available to the public. As the museum explained in a statement, “Images in the public domain belong to our shared cultural heritage.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, artnet’s Kinsella reports that widening access to one’s collection can offer tangible benefits. In the six months after the Met launched its open access campaign, the website saw a 64 percent increase in image downloads and a 17 percent uptick in overall traffic to the online portal.

While the Art Institute of Chicago will have to wait a few months to assess the impact of its new access portal, Grosvenor, for one, is confident that open access will increase visitor numbers. As he writes on his blog, “The more people see images of a collection, the more people want to go and visit that collection.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/05/a7059b0c-53ca-4c38-b707-4cce07658ba8/1280px-nighthawks_by_edward_hopper_1942.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)