Why 150,000 Sculptures in the U.K. Are Being Digitized

The expansive campaign by Art U.K. wants open up a conversation on the medium

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/3a/c43a6dcb-642a-4a65-ab2c-a24e07552c2f/bbo_mkcd_art008_001.jpg)

Statues and figures of humans or animals, busts and heads, abstract works, religious or devotional objects, figurative memorials and tombs, detached and figurative architectural features, assemblage sculptures, preparatory works and maquettes will be digitized in an ambitious campaign to catalogue all of the United Kingdom’s public sculptures—yes, all of them.

In total, Martin Bailey of the Art Newspaper reports, that’s 150,000 entries, including 20,000 works displayed within museums and buildings and 130,000 or so found outdoors.

The initiative marks Art U.K.’ s second foray into the world of mass digitization. Between 2003 and 2012, the nonprofit organization, which stems from the Public Catalogue Foundation charity, chronicled, photographed and digitized 212,000 of the country’s public oil paintings. This time around, as the organization turns its eye on statues, the digitization process is expected to be far faster, with a projected finish line of late 2020, according to the Guardian’s Mark Brown.

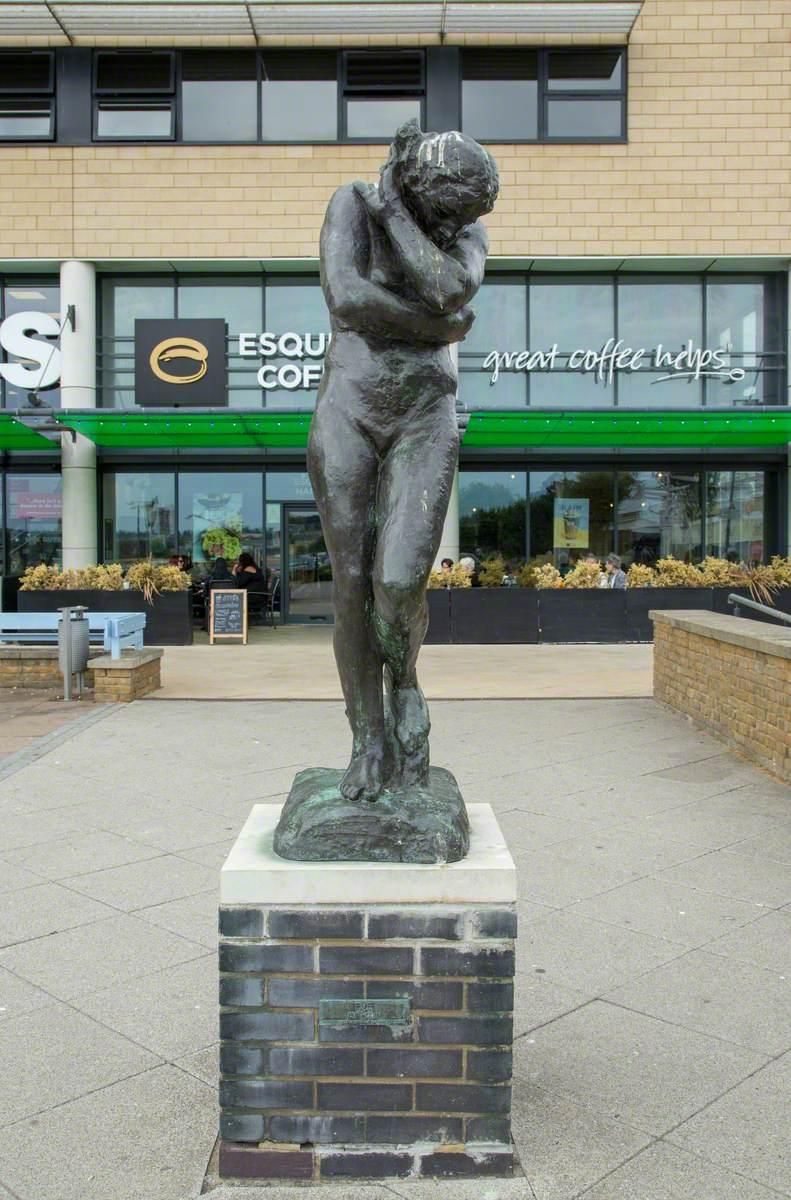

An initial crop of 1,000 works, including Auguste Rodin’s bronze cast of biblical first woman Eve, Elisabeth Frink’s water-dwelling “Boar” and Bruce Williams’ towering aluminum panel of six couples kissing, was already published last week.

Art U.K.’s Katey Goodwin and Lydia Figes define the parameters for sculptural works included in the project in a blog post. “[F]or the sake of making this a manageable and cost-effective project, we had to be selective and choose which types of three-dimensional art to include–and what not to include,” they write. Decorative and “functional” objects, as well as antiquities crafted prior to 1000 A.D., are among the works that won’t make the cut. Pieces brought to Britain from other countries—Bailey highlights a 15th-century Nigerian Benin bronze head—will be included.

The most prominent sculpture currently listed on the database is likely Rodin’s “Eve,” an 1882 statue that now stands outside of a Nando’s in the English county of Essex. The French sculptor originally designed “Eve” for a “Gates of Hell” commission he spent nearly 40 years crafting. At the time of Rodin’s death, the monumental work remained unfinished. “Eve” eventually ended up in Paris’ Musée Rodin; in 1959, a British art curator convinced the museum to part with the cast, which he then moved to the Essex hamlet of Harlow.

Other entries of interest include abstract sculptor Barbara Hepworth’s hand-carved “Contrapuntal Forms,” Bernard Schottlander’s undulating steel “Calypso,” and a trio of seated Buddha figures dating to the 1800s. The full catalogue of works is available via Art U.K.’s website.

According to a press release, one of the campaign's aims is to promote critical discussion of specific sculptural works. Potential lines of inquiry include why the database features so few sculptures of women and what is being done to redress this balance, how to discuss Britain’s legacy of slavery and colonialism when sculptures commemorate those who profited from them, and what sculpture can reveal about a post-Brexit Britain.

There’s also the larger question of the artistic merits of the medium overall. “Most people, when they think about art, will probably think about paintings rather than sculpture, and that’s slightly odd because we walk past sculptures and public monuments all the time,” Art U.K. director Andrew Ellis says in an interview with Apollo’s Florence Hallett.

The debate over which medium reigns supreme goes way back, and it is perhaps best characterized by the so-called paragone argument, which found Renaissance Old Masters such as Titian, Jan van Eyck and Petrus Christus vouching for painting with as much fervor as sculptors like Donatello and Ghiberti argued for sculpture’s superiority, according to Oxford Art Online.

While Goodwin and Figes argue that sculpture has long been relegated as an “afterthought to painting,” the burgeoning Art U.K. database may be able to add some nuance to that conversation, showcasing the diverse forms of expression afforded by the medium—from realistic busts of historical figures to streamlined abstractions to eclectic works you might not even register at first glance as sculpture.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)