Remembering Arthur Mitchell, the Barrier-Breaking Black Ballet Dancer

Mitchell joined the New York City Ballet in 1955 and later founded the Dance Theater of Harlem

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/4f/524f5e90-4c91-4bc3-9834-345b070aafc2/a6xc36.jpg)

When “Agon” the trailblazing contemporary ballet by master choreographer George Balanchine premiered in 1957, it wasn't only the performance's demanding choreography that shocked audiences. Balanchine’s central pas-de-deux in the ballet was crafted especially for two leading dancers at the New York City Ballet: Diane Adams and Arthur Mitchell. Adams was white. Mitchell was black. In those early years of the Civil Rights Movement, the pairing was scandalous.

“Can you imagine the audacity to take an African-American and Diana Adams, the essence and purity of Caucasian dance, and to put them together on the stage?” Mitchell recalled earlier this year, in an interview with Gia Kourlas of the New York Times. “Everybody was against [Balanchine].”

Later footage of the sparse, yet complex ballet (which the New York Times’ dance critic at the time noted was “about as difficult a work as any that has yet been produced”) captures Mitchell’s grace and skill as a performer. “[Y]ou watch it and it's just mesmerizing,” says Kinshasha Holman Conwill, deputy director of Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, who knew Mitchell as a colleague and friend.

“He had this extraordinary body, and he had absolute command of it,” Conwill adds. “The presence that I see in those videos is the presence that I felt with him as he moved through the world.”

The footage offers just a glimpse into Mitchell’s long and illustrious career spent breaking barriers for black ballet dancers. The esteemed performer died this week at the age of 84; according to Sarah Halzack of the Washington Post, the cause of death was renal failure.

As a dancer, Mitchell performed around the globe to great acclaim. But the accomplishment that brought him the most pride, he told Kourlas in January, was founding the Dance Theater of Harlem, a ballet school comprised of mostly black performers.

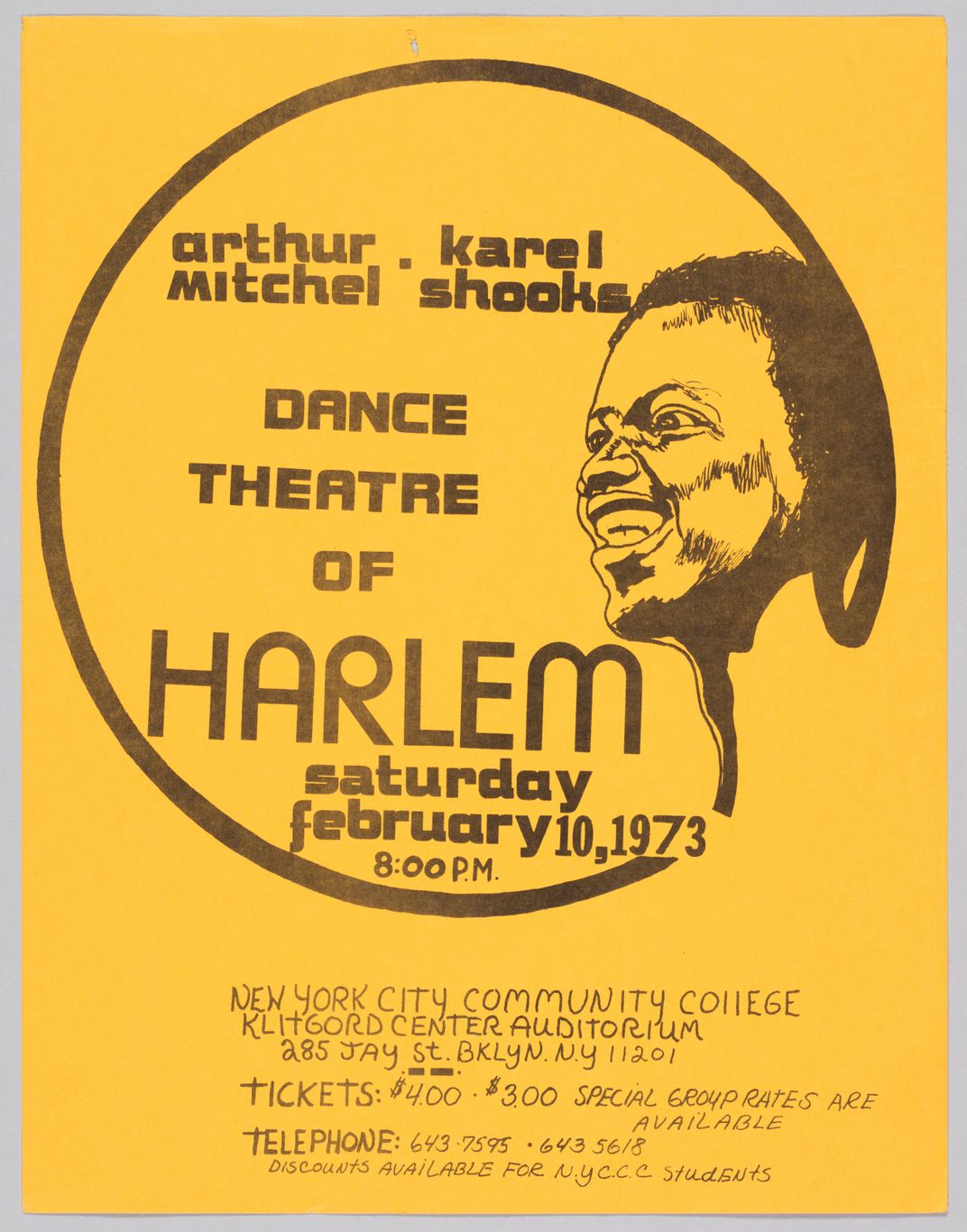

Mitchell was born in Harlem, New York, in 1934. His road to international stardom began when a school guidance counsellor spotted him dancing the jitterbug and suggested he apply to New York’s High School of Performing Arts. He won a scholarship there for his interpretation of "Steppin' Out with My Baby,” and began performing with the school’s modern dance troupe. At the age of 18, Mitchell started studying with Karel Shook, a renowned white ballet teacher who encouraged black performers to train in classical dance, reports Jennifer Dunning of the New York Times.

By the time he graduated from the High School of Performing Arts, Mitchell had been offered two scholarships: one for modern dance at Bennington College in Vermont, the other for ballet at the School of American Ballet, the official academy of Balanchine’s company, the New York City Ballet.

Ballet was an especially difficult path for Mitchell to take; at the time, Conwill explains, racist ideologies fueled the perception that black people were unable to perform classical dance. Undaunted, Mitchell decided to accept the School of American Ballet’s offer, with the intent "to do in dance what Jackie Robinson did in baseball."

He did just that and was invited to join the New York City Ballet for its 1955-1956 season. Speaking to Kourlas, Mitchell recalled hateful comments made by other dancers and their parents. “There were many people that said there shouldn’t be blacks in ballet, and Balanchine said, ‘Then take your daughter out of the company,’” Mitchell remembered. “He always stood up for me.”

Mitchell’s first major role was as the lead in Balanchine’s “Western Symphony.” When he danced onto the stage, he could hear gasps coming from the audience. Balanchine, however, was concerned only with Mitchell’s exceptional talent. In addition to casting Mitchell in “Agon,” Balanchine featured him as a nimble-footed Puck in the City Ballet’s 1962 performance of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

“Beyond any particular style, he brought that aspiration and that certitude that black people could do ballet,” Conwill notes.

After more than a decade with Balanchine’s company, Mitchell was asked to organize an African-American ballet company to perform at a Senegal world festival celebrating black artistry. He went on to establish a national ballet company in Brazil. But in April 1968, while heading to the airport for one of his trips to South America, Mitchell heard the shocking news that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. He decided not to stay in the U.S. and focus his efforts on making a difference for black Americans.

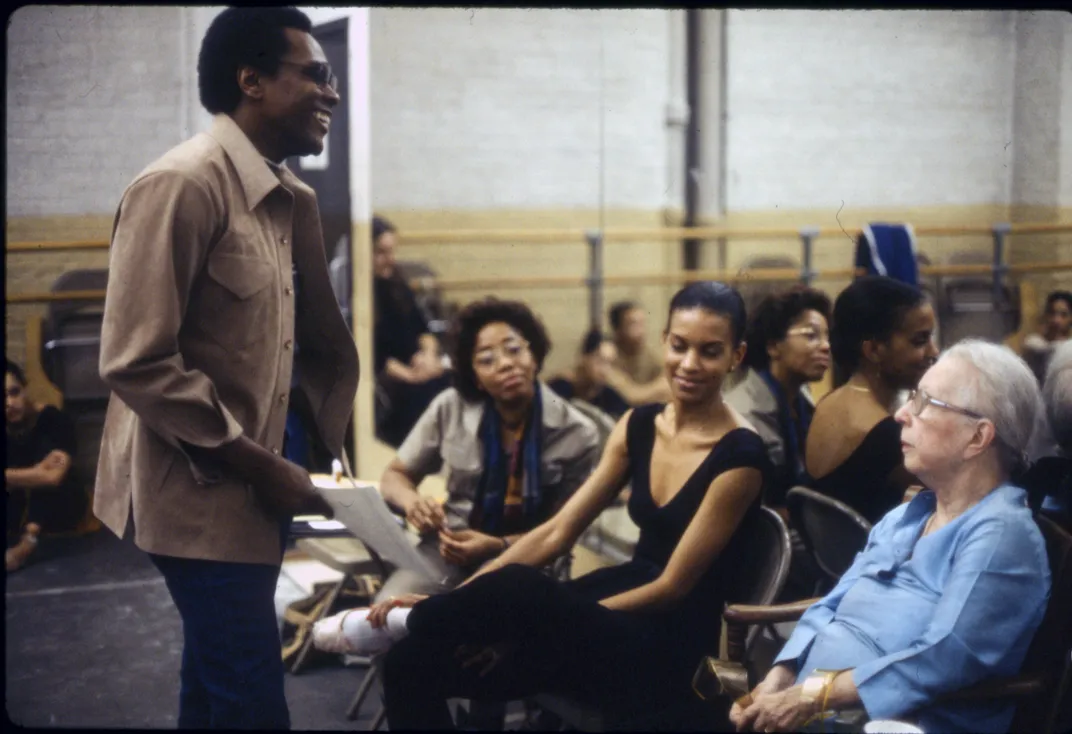

That year, Mitchell and his former teacher Shook established the Dance Theater of Harlem. The school started in a remodeled garage with only two students; soon, attendance ballooned to 400 students.

By bringing ballet to Harlem, Mitchell showed that his talents, while considerable, were not exceptional among people of color; given the opportunity, other black dancers could excel at this elite, classically European art form. The Dance Theater of Harlem also created a supportive environment, where students could hone their craft “in the midst of people who start with the notion that you can—who don't start with the notion that you shouldn't be here,” Conwill says.

Conwill first met Mitchell after moving to New York in 1980 to work as the deputy director of the Studio Museum in Harlem. They were part of a group of cultural organizers who advocated for the community, and a natural friendship took root, which continued to bloom over the decades. Conwill recalls seeing Mitchell at the Dance Theater of Harlem’s open houses, instructing new generations of ballet dancers.

“He was telling the littlest people how to do the dance positions, how to do the movements,” she says. “He didn't expect them to do it the way … his principal dancers did, but he expected them to aspire to that.”

Mitchell was proud of his storied career—he called himself “the grandfather of diversity”—but Conwill says he never took himself too seriously.

“He could be in a group large or small, expounding either on dance theater and why he started it or on classical ballet, and then just burst into laughter and be self-deprecating,” she remembers. “I adored him.”