Audubon Pranked Fellow Naturalist by Making Up Fake Rodents

Annoyed with naturalist and houseguest Constantine Rafinesque, John J. Audubon dreamed up 28 non-existent species

In 1818, the prodigious and strange European naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque took a trip down the Ohio River Valley, collecting specimens and accounts of plants and animals along the way. During this venture, he often stopped to visit or stay with fellow botanists and naturalists. That’s how he found his way into the home of artist and naturalist John James Audubon in Henderson, Kentucky, in August of that year, reports Sarah Laskow at Atlas Obscura

During the stay, Audubon pulled a fast one on Rafinesque, describing and sketching for him 11 outlandish fish species, including the 10-foot-long Devil-Jack Diamond fish with supposedly bulletproof scales. Rafinesque even published accounts of the faux fish in his book Icthyologia Ohiensis, writes Kira Sobers, a digital imaging specialist at the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

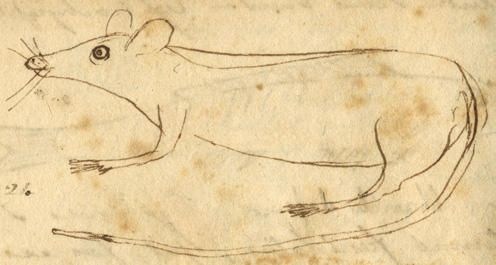

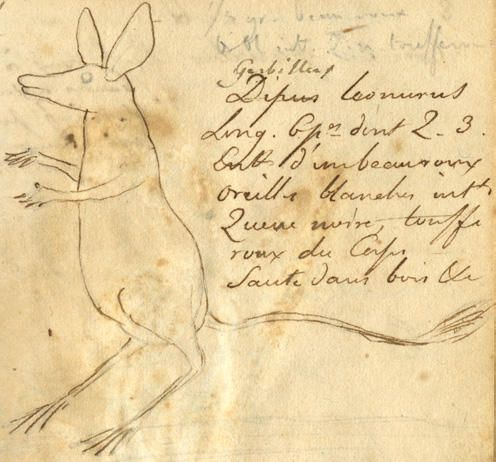

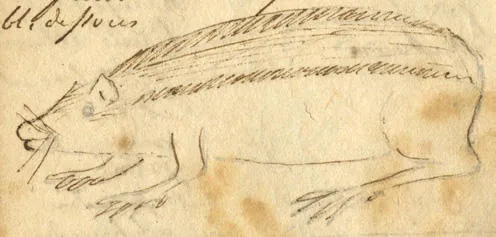

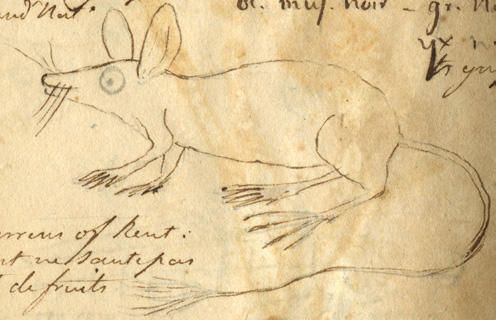

Researchers identified the prank well over a century ago. But until now they didn’t realize that Audubon fed Rafinesque a lot more than fanciful fish. According to a new paper in Archives of Natural History, Audubon also fabricated two birds, a “trivalve” mollusk-like creature, three snails, and two plants. He also came up with nine “wild rats,” some of which Rafinesque later described in the American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review.

“Audubon may have thought that Rafinesque would realize the prank, and he probably considered it unlikely that the eccentric naturalist would be capable of publishing his descriptions in scientific journals,” writes Neal Woodman, the author of the paper and mammal curator at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. “If so, he underestimated both Rafinesque’s trusting naïveté and his ingenuity in finding and creating outlets for his work.”

While Rafinesque credited Audubon for the fake fish, he did not link the strange rodents to him—one reason it took so long to discover the prank. But the Smithsonian’s Field Book Project sniffed out the ruse. This initiative creates freely available digital copies of the Institution’s vast collection of notebooks from naturalists and explorers. Rafinesque’s journal is one of the oldest of the collection.

“That journal is very special and one of our favorite examples of how unique and rich our holdings can be,” Lesley Parilla cataloging coordinator for the Field Book Project tells Smithsonian.com. “Rafinesque was quite a colorful character and a bright man but not one that followed the party line. He made beautiful drawings, but his handwriting is really hard to read.”

So why would Audubon, one of the America’s great naturalists, fabricate species? Researchers speculate that the answer lies in a likely embellished version of Rafinesque's visit Audubon published years later called “The Eccentric Naturalist.”

According to that account, Audubon awoke one night to find a naked Rafinesque running around his room, swinging Audubon’s favorite violin at bats that had gotten in through an open window. Convinced the bats were a new species, Rafinesque wanted to swat the little mammals down. A displeased Audubon took the violin remnants and finished the job, doubting the bats were anything special.

As Allison Meier at Hyperallergenic writes, the fish stunt may have cost Audubon some credibility. He was later accused of making up five of the birds in his 1827 magnum opus Birds of America—species that were likely hybrids, extinct, or rare color morphs.

Woodman points out that Audubon also received karmic retribution for the stunt. His friend John Graham Bell was traveling with him in the 1840s as an assistant and taxidermist when the two separated for a week. While Audubon was gone, Bell sewed together the head, body and legs of different birds. Surprised by the creature, Audubon sent out an account right away. Weeks later, when Bell confessed, Audubon was livid, but soon saw the humor in the trick.

“Audubon himself fell victim to a prank similar to the one he played on Rafinesque,” writes Woodman. “To his credit, Audubon at least had a specimen in hand.”