Aztec Pictograms Are the First Written Records of Earthquakes in the Americas

New analysis of the 16th-century “Codex Telleriano-Remensis” reveals 12 references to the natural disasters

:focal(430x285:431x286)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/04/18048143-b412-450e-9bc9-b5ee80a99c31/t-r-codex-mexico-16th-century-800px.jpeg)

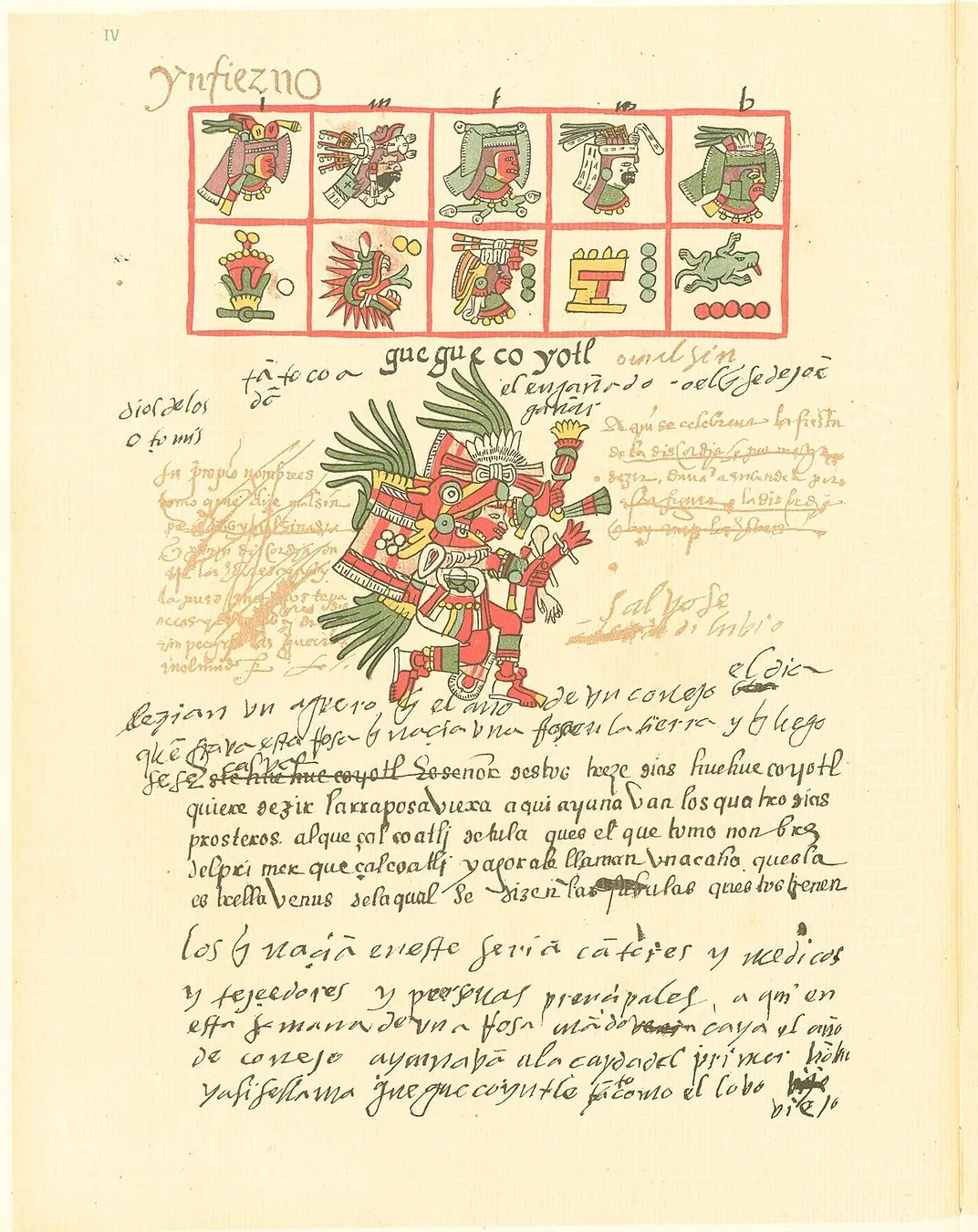

A 16th-century Aztec manuscript known as the Codex Telleriano-Remensis contains the oldest surviving written record of earthquakes in the Americas, reports David Bressan for Forbes.

As Gerardo Suárez of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Virginia García-Acosta of the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social write in the journal Seismological Research Letters, the codex contains references to 12 separate earthquakes that took place in the region between 1460 and 1542.

“It is not surprising that pre-Hispanic records exist describing earthquakes for two reasons,” says Suárez in a statement from the Seismological Society of America. “Earthquakes are frequent in this country and, secondly, earthquakes had a profound meaning in the cosmological view of the original inhabitants of what is now Mexico.”

The pictograms, or drawings, provide little information about the earthquakes’ location, size or scale of destruction. Coupled with other records written after the Spanish Conquest, however, they offer modern scholars a new perspective on Mexico’s seismic history. Forbes notes that the team used symbols representing solar eclipses or specific days, as well as Latin, Spanish and Italian annotations added to the codex by later observers, to date the earthquakes.

One pictogram highlighted in the study depicts soldiers drowning as a building burns in the background. Researchers matched the event to a 1507 earthquake that damaged a temple and drowned 1,800 warriors in a river likely located in southern Mexico. The quake coincided with a solar eclipse—a phenomenon represented in the codex by a circle with lightning bolts coming out of it.

According to Spanish newspaper Vozpopuli, pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican societies viewed the universe as cyclical, with periods known as “suns” ending in floods, fires, earthquakes and other natural disasters before new eras began. Each of the five suns was broken down into multiple 52-year cycles.

Referred to as tlal-ollin or nahui-ollin in the Indigenous Nahuatl language, earthquakes are represented in Aztec pictograms by two symbols: ollin (movement) and tlalli (Earth). Per the study, ollin consists of four helices symbolizing the four cardinal directions, while tlalli features one or multiple layers of multicolored markings denoting precious gemstones. The codex contains other iterations of these glyphs, but experts are unsure what they signify.

Aztec codices chronicle the civilization’s history and mythology through “unique symbols, writing and calendric systems,” notes Fordham University. The Codex Telleriano-Remensis is broken down into three sections: a calendar; a handbook detailing ritual practices; and an account of Aztec migration from the late 12th century to 1562, when Mexico was under control of Spanish colonizers.

As David Keys wrote for the Independent earlier this year, modern historians have long overlooked the Aztecs’ “intellectual and literary achievement[s].” But new research conducted by British anthropologist Gordon Whittaker is challenging this limited view, demonstrating that Aztec script was far more sophisticated than often believed.

“Sadly, many scholars over the centuries have tended to dismiss the Aztecs’ hieroglyphic system because it looked to Europeans like picture-writing,” Whittaker, author of Deciphering Aztec Hieroglyphs, told the Independent in April. “In reality, it wasn’t—but many art historians and linguists have mistakenly perceived it in that way.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)