This Ball of Thread Is 3,000 Years Old

If it is simply held in the wrong way, the priceless artifact could crumble to pieces

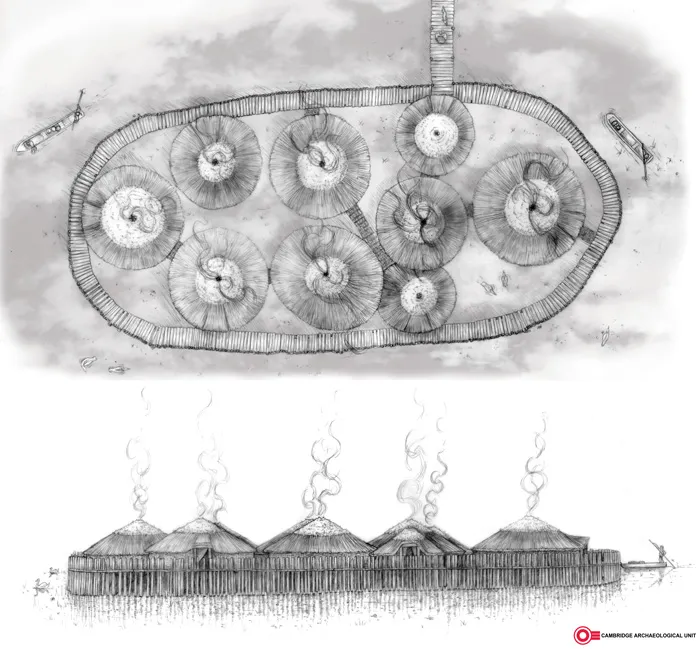

Thousands of years ago, a small village in a bog near what is now Cambridge, England was razed by a fire. The flame torched the village's buildings and sending their contents into the muck below. Millennia later, archaeologists studying the ruins have uncovered artifacts dating back to the Bronze Age that reveal new insights into the lives of the people who once lived in this settlement – including, remarkably, skeins of yarn and balls of thread.

Fabrics made by ancient people rarely survive into the modern day because the materials are so fragile. However, the town—now known as “Must Farm”—was built on stilts above a bog that preserved the village’s ruins when it was destroyed and sank into the mud 3,000 years ago, Sarah Laskow reports for Atlas Obscura. That wooden fragments of buildings and many household goods survived the long years of being buried underground is striking enough. But the thread and yarn recovered from the site is an especially precious find. If it is simply held in the wrong way, the priceless artifacts could crumble to pieces.

“Occasionally we find archaeology that is hard to comprehend,” the researchers wrote on the Must Farm Facebook page last week. “When we first started finding such incredibly preserved textiles it was very difficult to believe it could really be 3,000 years old given how amazing its condition was.”

In the months since archaeologists began excavating the site, they have uncovered the largest collection of Bronze Age fabrics known today. Thanks to being charred by the fire and quickly being buried underground, the threads, yarns and linens survived alongside hardier artifacts like pottery and bronze tools, Erik Stokstad writes for Science Magazine.

According to University of Glasgow archaeologist Susanna Harris, the fabrics are among the best quality discovered from that time period. When she examined the delicate thread tread recovered from Must Farm, she was shocked to discover that some of them had thread counts of up to 30 per centimeter—some of the best cloth available in Europe at the time.

But while the fabrics survived, Harris says its unclear what they were used for. Researchers studying ancient fabrics often rely on other elements of certain garments to clue them in on their purpose, such as sleeve cuffs, Stokstad reports. However, if the fabric found at Must Farms were once parts of clothing, blankets, or some other function, the identifying markers have long since disappeared.

Among other finds at Must Farm, researchers have discovered utensils used for cooking and eating, bowls with the remains of food still crusted into them and even intact portions of thatched roofs—another rarity from the Bronze Age. With the excavation winding down and the artifacts being shipped to labs for further study, more insight into the daily lives of the Bronze Age villagers seems sure to follow.