Remembering the Forgotten Female Artists of Vienna

New exhibition draws on works by around 60 women who lived and worked between 1900 and 1938

:focal(487x181:488x182)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/96/9d9678bf-43e8-4c46-b476-8573036ee2f9/_105323169_mediaitem105323168.jpg)

Teresa Feodorowna Ries’ marble sculpture of a nude young woman clipping her toenails with a pair of garden shears catapulted her to fame overnight.

Tastemakers had actually derided the puckish work, titled “Witch Doing Her Toilet on Walpurgis Night,” as “atrocious,” tasteless” and a “grotesque apparition” when it was first exhibited at Vienna’s Künstlerhaus in the spring of 1896. But, as the Art Blog’s Andrea Kirsh attests, the Russian-born Jewish artist never meant to please the men who dominated Vienna’s turn-of-the-century art scene. And while critics may have been scandalized by the life-size work of a young woman who embraced her own power, the sculpture did manage to draw the eye of none other than Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph I, who spoke to Ries at length during the opening, “guaranteeing good coverage in the press,” as art historian Julie M. Johnson chronicles in a 2012 monograph, The Memory Factory: The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900.

More than a century later, Ries and the many female artists who contributed to the success of Viennese Modernism are largely absent from the canon, while male artists such as Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele remain household names.

But a new exhibition at Vienna’s Belvedere Museum, titled City of Women: Female Artists in Vienna From 1900 to 1938, is endeavoring to bring these artists back into the conversation. According to BBC News, the show draws on works by around 60 artists, including Ries, French Impressionist follower Broncia Koller-Pinell, controversial portraitist Elena Luksh-Makowsky, and the Impressionist- and Fauvist-inspired Helene Funke.

The artists featured in the exhibition faced significant barriers to acceptance in the Viennese art world. Although the Academy of Fine Arts opened its doors to women in 1920, prior to this date, those seeking advanced artistic training were forced to pay for expensive private lessons (providing they could afford such lavish expenses).

As a Belvedere press release notes, female artists were barred from joining such influential associations as the Künstlerhaus, the Secession—an avant-garde separatist movement led by Klimt—and the Hagenbund; opportunities to exhibit, such as the 1896 show involving Ries, were few and far between.

To better level out the playing field, a group of women founded the Austrian Association of Women Artists, or VBKÖ, in 1910. An exhibition launched soon after the organization’s founding seemingly anticipates the Belvedere’s newest venture; according to the VBKÖ’s website, this Art of Woman show traced the history of women’s art from the 16th century through the 20th.

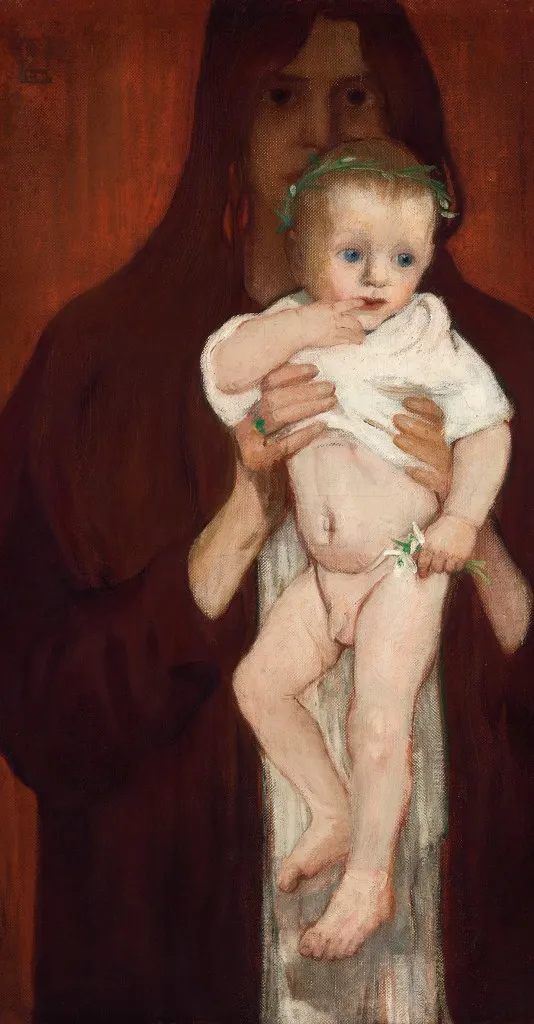

The progress represented by the VBKÖ and increasing recognition of such artists as Koller-Pinell, who serves as “a common thread uniting … different” movements in the Belvedere exhibition; Tina Blau, a predominantly landscape painter who achieved a level of critical success often withheld from women; and Luksch-Makowsky, whose 1902 self-portrait attracted controversy for its portrayal of the overall-clad artist and her son in Madonna and Child-esque poses, came to a startling halt in 1938, the year Nazi Germany annexed Austria.

During World War II, Vienna’s artists suffered not only from the Nazis’ labeling of modern art as “degenerate,” but, in the cases of those with Jewish heritage like Ries, outright persecution. BBC News highlights Friedl Dicker, a left-wing Jewish artist who catalogued Nazi abuses in works such as “Interrogation I” and was eventually murdered at Auschwitz, and Ilse Twardowski-Conrat, a sculptor who destroyed her most significant works before committing suicide in 1942.

As the press release explains, few of the artists forced into exile ever managed to resuscitate their careers. The result, Catherine Hickley writes for the Art Newspaper, was a post-war emphasis on the female modernists’ “more famous male counterparts.” Although these women have enjoyed a resurgence of attention in recent decades, most of their names remain little-known today.

Excitingly, curator Sabine Fellner tells Hickley that the Belvedere show includes a number of works that have long been buried in archives—a fact sure to promote renewed reflection on and analysis of the artists' accomplishments.

Fittingly, another one of Ries’ marble sculptures stands at the center of the exhibition: “Eve,” crafted in 1909, depicts the biblical figure curled into a fetal position. In her memoir, as cited by The Memory Factory, Ries wrote that the vulnerable pose was inspired by women’s lot in life. “I could not understand why the woman could not gain a better position in history, that the secondary role in the history of humankind seemed to suffice—woman, in whose womb humanity begins and ends,” she wrote.

“And yet,” Ries added with resignation, “this seemed to be the fate of women since the time of Eve, since the first sin.”

City of Women: Female Artists in Vienna from 1900 to 1938 is on view at the Belvedere in Vienna through May 19, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)