Blokes with Metal Detectors Uncover Pieces of British History

Finds by amateur history sleuths shed light on the time when Anglo-Saxons clashed with Vikings

In the U.S., average Joes with metal detectors tend to find old nails, some coins, lost wedding rings and the occasional meteorite. But, in Great Britain, there can be a lot more at stake—the landscape is dotted with Anglo-Saxon and Viking treasures that amateur “detectorists” occasionally uncover. Since 1997, amateur history sleuths have made approximately 1 million archeological discoveries in the UK. Recently, two of these "detectorists" discovered objects dating back to 870 A.D. that shed a more complex light on relations between Vikings and Anglo-Saxons.

Back in October, retired advertising executive Jim Mather was searching farmland near Watlington, in Oxfordshire, when he realized he was looking at a Viking hoard, treasure buried in times of trouble or as offerings to the gods. He alerted the authorities, who helped excavate the clump of soil that looked like “a greasy haggis with bits of treasure sticking out at the corners,” according to the Guardian.

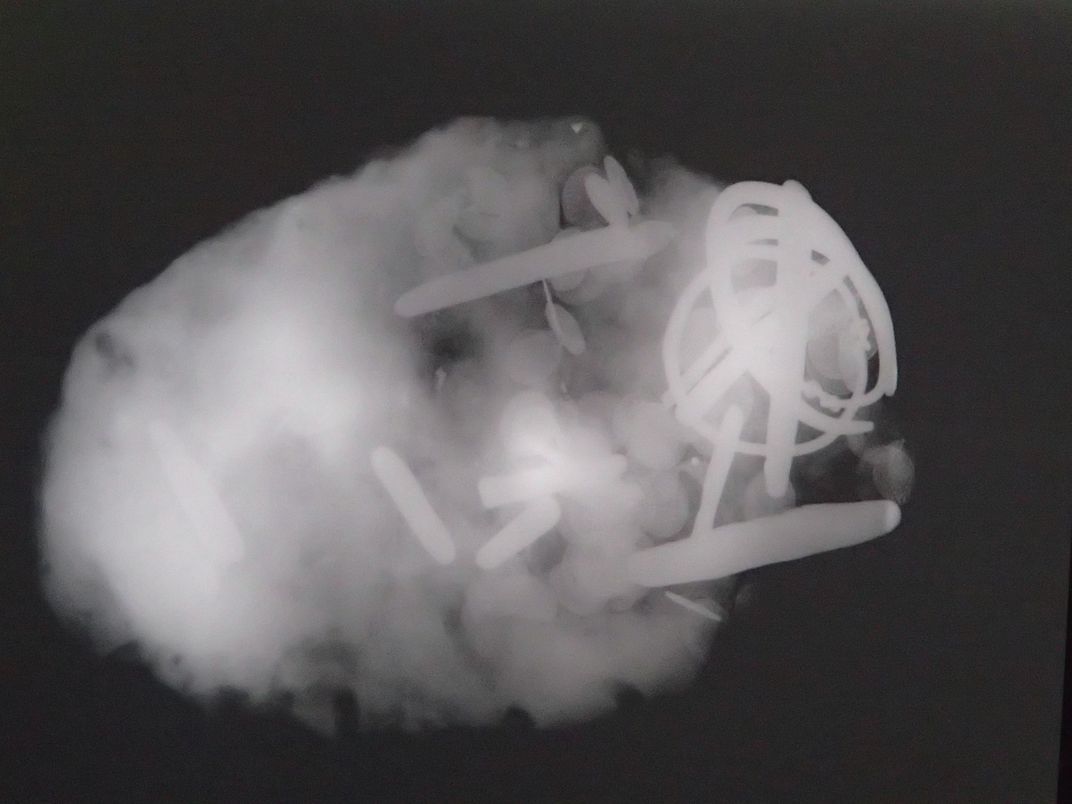

When researchers at the British Museum broke open the clump, they found it contained chopped up gold, 15 silver ingots, 3 Viking arm bands and 186 silver coins, which dated the stash to the 870s A.D. As a local paper, the Henley Standard reported, the government recently declared the find “treasure,” meaning Mather has the right to profit from the find, estimated at more than 1 million British pounds.

The hoard might have made Mather a pretty penny, but the find is much more valuable to historians. According to Annalee Newitz at Ars Technica, before his discovery, archeologists had recovered only one coin bearing the likeness of Ceolwulf II, the ruler of a large kingdom in central England called Mercia. As the Telegraph reports, he is only mentioned a few times in Anglo-Saxon accounts, and not in a flattering light.

What the new coins show, however, is that Alfred the Great of the neighboring kingdom of Wessex, 871-899, who conquered Mercia, was probably in alliance with Ceolwulf, at least for awhile. The coins depict the two rulers side by side and were minted in both kingdoms, meaning the relationship was stable enough and lasted long enough for them to produce a common currency.

"Poor Ceolwulf gets very bad press in Anglo-Saxon history, because the only accounts we have of his reign come from the latter part of Alfred’s reign," Gareth Williams, curator of Early Medieval coinage at the British Museum, said at a press conference. "Here is a more complex political picture in the 870s..."

Another significant stash of artifacts was discovered by Graham Vickers, a metal detectorist who found a stylus, an ornate silver writing implement, in a field near Little Carlton, Lancashire, in 2011. According to a press release, after alerting the authorities, 20 more styli, 300 dress pins, coins from the 7th and 8th centuries as well as pottery from Germany and other trade good from continental Europe were recovered at the site.

That got the attention of archeologists from the University of Sheffield who visited the site and conducted a 3D survey. They recently publishing their findings in Current Archaeology, and as the BBC reports, the discovery pointed to the area being a “high-status” trading village.

Newitz at Ars Technica writes:

This discovery in Little Carlton expands our knowledge about that time dramatically, suggesting that the English coast was swarming with traders. The styluses are especially interesting, because they hint at a populace that was literate, sending written letters beyond the confines of their town—perhaps to other parts of England or to trading partners on the continent.

As LiveScience reports, the trading post was abandoned around in the late 800s, possibly the victim of a Viking invasion.

That these sites were found by hobbyists who brought them to the attention of archeologists instead of looting them is impressive in its own light. As Hugh Willmott one of the archeologists working in Little Carleton pointed out in a press release, “Our findings have demonstrated that this is a site of international importance, but its discovery and initial interpretation has only been possible through engaging with a responsible local metal detectorist.”