Boston Removes Controversial Statue of Lincoln With Kneeling Freed Man

The sculpture, installed in 1879, is based on one still standing in Washington, D.C.

:focal(364x111:365x112)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/1f/321f7bf8-b1bd-443b-a785-7a58d3dd7c49/emancipation_group.png)

After months of public discussion, Boston officials have removed a controversial statue of President Abraham Lincoln with a formerly enslaved man kneeling at his feet.

“We’re pleased to have taken it down this morning,” a spokesperson for Boston Mayor Marty Walsh tells NPR’s Bill Chappell. “… The decision for removal acknowledged the statue’s role in perpetuating harmful prejudices and obscuring the role of Black Americans in shaping the nation’s freedoms.”

The Boston Art Commission voted in June to remove the sculpture after hearing public comments. Prior to the vote, Boston artist and activist Tory Bullock had circulated a petition that gathered some 12,000 signatures in support of the removal.

“This is a frozen picture,” Bullock said at the time of the vote. “This man is kneeling, he will never stand up. This image is problematic because it feeds into a narrative that Black people need to be led and freed. A narrative that seems very specific to us for some reason. Why is our trauma so glorified?”

Known as the Emancipation Group or Emancipation Memorial, the bronze statue is a replica of one installed in Washington, D.C. in 1876. Per the Boston Arts and Culture website, Moses Kimball, a politician and founder of the Boston Museum, donated the copy to the city in 1879.

Arthur Alexander, the model for the man shown kneeling at Lincoln’s feet, was born into slavery in Virginia around 1813. During the Civil War, he escaped from his enslaver and traveled 40 miles to seek protection from Union troops, writes University of Pittsburgh historian Kirk Savage in Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves. Alexander is said to have helped the Union Army by providing intelligence about pro-Confederate activity; depending on the account, the information centered on either a sabotaged bridge or a stash of hidden weapons.

After his escape, Alexander found work tending the garden and orchard of William Greenleaf Eliot, a minister and founder of Washington University in St. Louis. (Eliot’s grandson later found fame as poet and playwright T.S. Eliot.) A gang of men sent by his enslaver found him, beat him unconscious and detained him at the city jail, but he was later freed. Alexander became famous through a partly fictionalized book that Eliot wrote about him, reports DeNeen L. Brown for the Washington Post. Published posthumously, the text presented its subject as “in many things only a grown-up child.”

Alexander became the model for the formerly enslaved man in D.C.’s Freedman’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln thanks to Eliot’s efforts. The minister had photos of him sent to sculptor Thomas Ball, who used them to create the face of the kneeling man. Formerly enslaved people contributed much of the money for the statue but lacked creative control over the monument.

As historians Jonathan W. White and Scott Sandage reported for Smithsonian magazine in June, some at the time, including reformer Frederick Douglass, had reservations about the design. In an 1876 letter, Douglass wrote that “what I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-legged animal but erect on his feet like a man.”

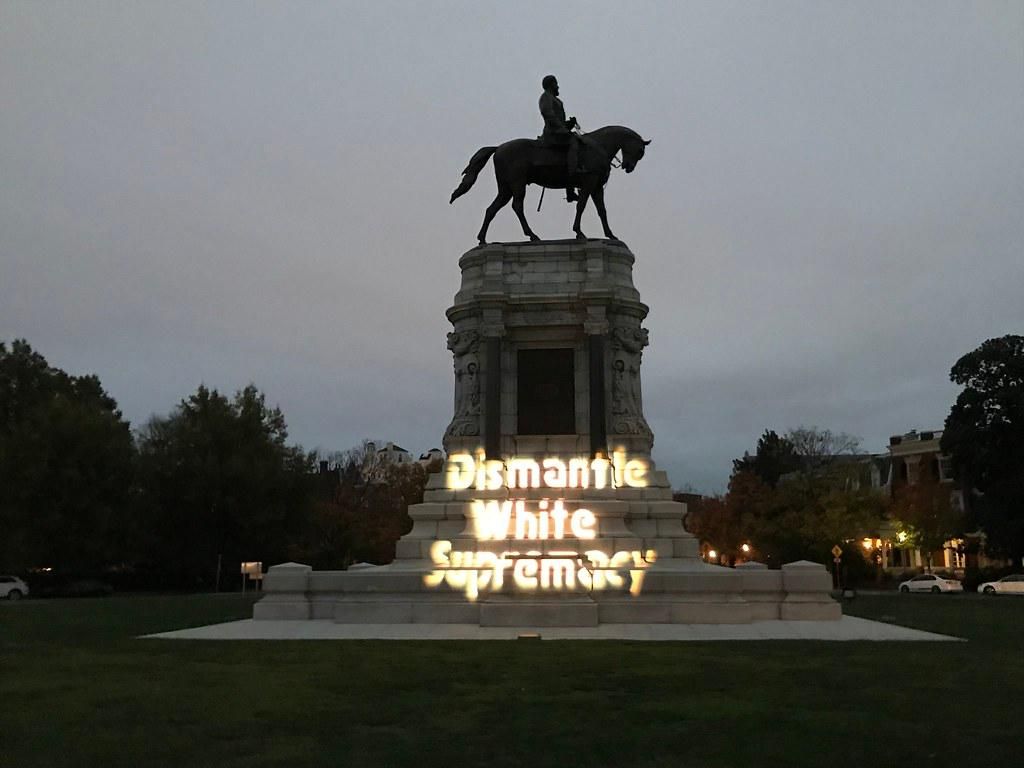

Debate about the statue reignited this summer in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd. Activists across the country tore down Confederate monuments and other public art seen as celebrating racism. Months later, American citizens and government officials continue to reckon with the question of how to handle these controversial works.

The Boston Art Commission and the Mayor’s Office of Arts are now seeking public comments on a new location for the statue, as well as ideas for reconceiving the site. This winter, the city is planning to host a series of virtual panel discussions and short-term art installations “examining and reimagining our cultural symbols, public art, and histories,” a spokesperson tells CNN’s Christina Zdanowicz and Sahar Akbarzai.

As Gillian Brockell reports for the Washington Post, the original D.C. statue has also attracted criticism. Over the summer, officials surrounded the memorial with protective barriers to discourage activists from attempting to tear it down. The statue is on federal land administered by the National Park Service, and D.C. Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton is working to determine whether the government agency can remove it without congressional approval. She has also introduced legislation to move the sculpture to a museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)