Bullets That Killed John F. Kennedy Immortalized as Digital Replicas

The originals remain at the National Archives, but new 3-D scans showcase the ballistics in vivid detail

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/00/1900512e-d779-4b36-a9f3-baad244a7832/jfk-3d-artifacts-wide-64.gif)

After years under lock and key at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the bullets that killed President John F. Kennedy will soon be accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

In partnership with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the National Archives has scanned the historic bullets to produce high-definition 3-D replicas set to be uploaded to an online catalog in early 2020.

The scans capture the infamous ballistics—including two fragments from the bullet that fatally wounded Kennedy—in microscopic detail, says NIST scientist Thomas Brian Renegar in a statement.

Even viewed on a screen, he adds, “It’s like they’re right there in front of you.”

Fifty-six years after the beloved president’s passing, his killing remains shrouded in controversy: Around 60 percent of Americans still believe Kennedy’s assassination was a conspiracy, according to a 2013 Gallup poll, though this figure has shrunk somewhat in the past several decades, Harry Enten reported for Five Thirty Eight in 2017. But by the official account, gunman Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, shooting at Kennedy as he rode in a presidential motorcade in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald reportedly fired three shots. One likely struck the backs of both Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally, who had joined the president in his limo, and was later recovered relatively intact from Connally’s hospital stretcher. Another hit the president’s head, fragmenting upon impact with his skull and delivering the fatal blow. Connally, who was sitting just in front of Kennedy, survived.

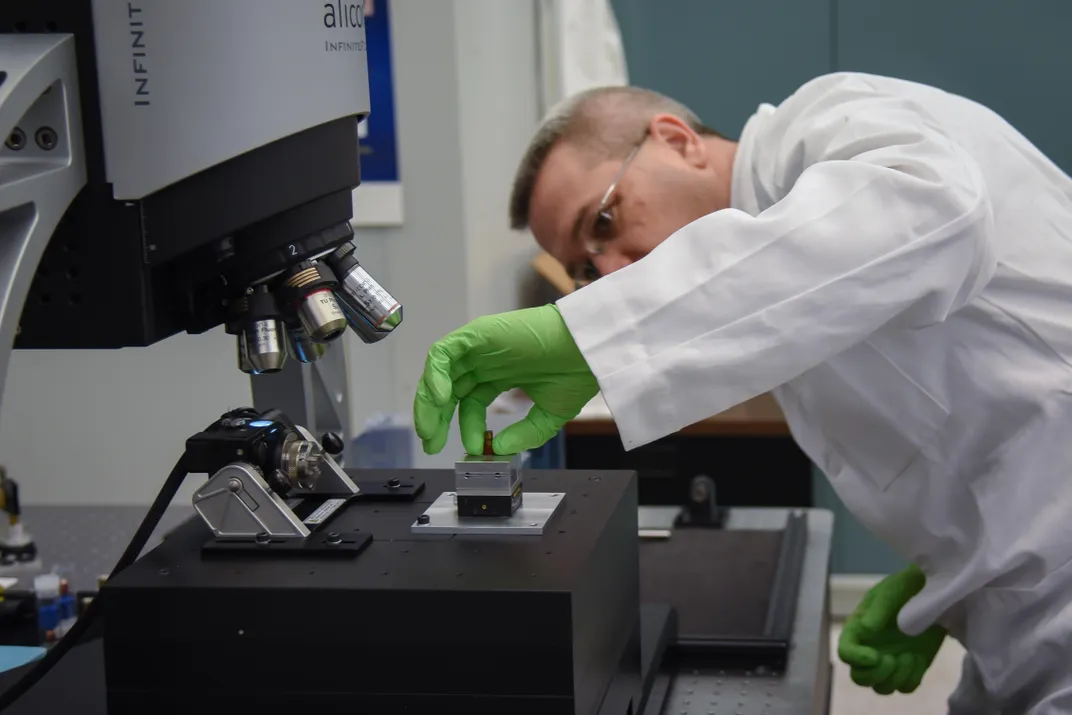

These bullets now enter the National Archives’ digital collection alongside three others thought to hail from the same firearm: two discharged as test shots, and another from an earlier failed assassination attempt on Army Major General Edwin Walker. All were imaged with a specialized microscope that scanned their surfaces, charting their features much like a satellite recording the topography of a mountain range. The pictures were then stitched together by NIST ballistics specialists to generate a vivid 3-D rendering detailed enough to show grooves left by the barrel of the gun.

Digital replicas aren’t the same as scoping out the actual bullets in person. But while those precious artifacts remain tucked away in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vault at the National Archives, the virtual copies will bring viewers “as close as possible to the real things,” says Martha Murphy, deputy director of government information services at the National Archives, in the statement.

“You’re going to see every groove in the bullet, every nick,” Murphy explains in a video detailing the preservation project. “It’s going to be a very true representation of the original.”

The collaborative project was conducted strictly for historic preservation, so neither team has conducted forensic analysis on the bullets. But any researchers interested in taking a fresh stab at the fragments will be able to do so once the scans go live sometime next year.

If all goes as planned, a long-awaited cache of files related to the official investigation of the assassination may join the digitizations in October 2021, Ian Shapira reported for the Washington Post last year.

For now, nearly six decades after the event, the documents remain redacted.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)