Byron Was One of the Few Prominent Defenders of the Luddites

Years later he even wrote them a poem, “Song for the Luddites”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/82/9982ed8f-7284-4d38-9fda-e368f48426c8/framebreaking-1812.jpg)

Automation reached the textile makers of northern England in the early nineteenth century, fundamentally changing the fabric of their lives.

Rather than accept their fate, Clive Thompson recently wrote for Smithsonian Magazine, some of the workers “fought back—calling themselves the ‘Luddites,’ and staging an audacious attack against the machines.”

When the textile workers (whose movement was named after anti-industrial folk hero Ned Ludd) waged war on the automation that threatened both their jobs and their way of life, they were met with the same opposition as many others who allegedly get in the way of progress.

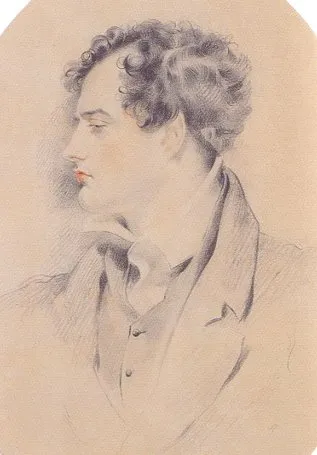

But they also had supporters, like Lord George Gordon Byron, writes Steve Melito for On This Day in Engineering History. On this day in 1812, just months after the textile workers had begun smashing the machines that were taking their jobs, Byron stood up in the House of Lords and defended them.

Byron is best-known as a capital-r Romantic. That means he was part of “an artistic and intellectual movement that railed against the scientific rationalization of nature,” Melito writes. The later part of that movement—which Byron is associated with—was full of men and women (including Jane Austen and Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein) confronting the first phases of the Industrial Revolution in their art.

What set Byron apart was that he was a lord, which gave him more say in how the country ran than your average artsy type. In this case, he used his power to stand up for the Luddites against Prime Minister Spencer Perceval, who was fighting for a bill that would make “machine-breaking” a capital offense. It was Byron’s first speech in the House of Lords, made two weeks before his first big hit, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, was published and he became famous as well as rich and powerful.

Speaking in front of the lawmakers, Byron “opposed Perceval’s efforts in the House of Lords, explaining that the Luddites’ recent acts of violence were the product of ‘circumstances of the most unparalleled distress.’ This ‘once honest and industrious body of the people,’ Byron claimed, had become ‘miserable men’ driven by ‘nothing but absolute want,'” writes Melito.

The role of defender of the Luddites likely would have appealed to Byron, whose signature character type was the Byronic hero—a passionate contrarian who fought against the prevailing beliefs of society. In true Romantic spirit, Byron put a lot of himself into his work. In fact, Childe Harold is considered to be at least semi-autobiographical.

But the Luddites needed all the help they could get. In the end, the pleas of Byron and others were ignored, and some of the Luddites paid the ultimate price. Executions took place after an 1813 sentencing in both Lancashire and York, including the execution of 12-year-old Abraham Charlston. Other Luddites were deported to Australia (then a penal colony). In late 1816, Byron immortalized the movement in a stirring poem sent to a friend.

But progress marched forward anyway. The textile workers found themselves working in the “dark, Satanic mills” of nineteenth-century industrial Britain, in the words of another Romantic poet.

Today, the word Luddite is an insult, meaning backwards or opposed to change. It’s levelled at those who stand in the way of technological change, which is truly a case of the winners writing the history books. But recall this: As Byron said in his speech, “You may call the people a mob, but do not forget that a mob too often speaks the sentiments of the people.”