Medieval Britain’s Cancer Rates Were Ten Times Higher Than Previously Thought

A new analysis of 143 skeletons suggests the disease was more common than previously estimated, though still much rarer than today

:focal(720x548:721x549)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/b8/38b846c0-ff66-4012-b7de-24f629666098/263380_web.jpeg)

Conventional wisdom has long held that cancer rates in medieval Europe, before the rise of industrial pollution and tobacco smoking, must have been quite low. But a new study of individuals buried in Cambridge, England, between the 6th and 16th centuries suggests that 9 to 14 percent of medieval Britons had cancer when they died.

As Amy Barrett reports for BBC Science Focus magazine, this figure is about ten times higher than the rate indicated by previous research. The team, which published its findings in the journal Cancer, estimated rates of the disease based on X-ray and CT scans of bones from 143 skeletons buried in six cemeteries across the Cambridge area.

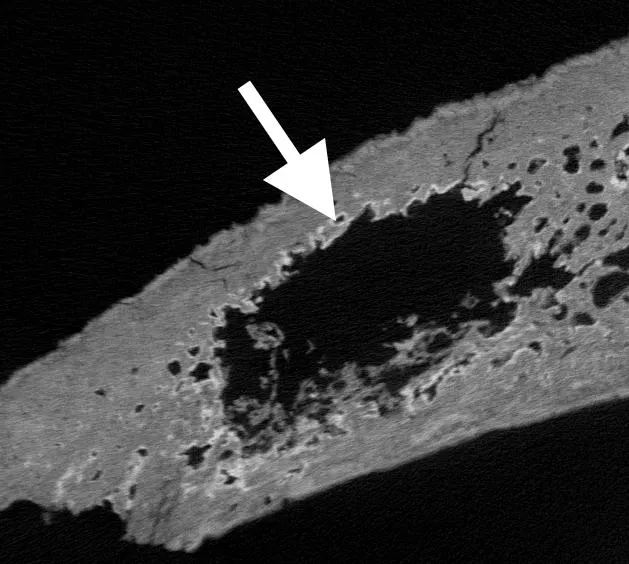

“The majority of cancers form in soft tissue organs long since degraded in medieval remains. Only some cancer spreads to bone, and of these only a few are visible on its surface, so we searched within the bone for signs of malignancy,” says lead author Piers Mitchell, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, in a statement. “Modern research shows a third to a half of people with soft tissue cancers will find the tumor spreads to their bones. We combined this data with evidence of bone metastasis from our study to estimate cancer rates for medieval Britain.”

While the researchers acknowledge that their sample size was relatively small and limited in geographic scope, they point out that it included people from many walks of life, including farmers and well-to-do urban residents.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/5f/165f5c33-8d69-4eb3-b190-a3c728d2c18a/263378_web.jpeg)

“We had remains from poor people living inside town, we had the rich people living inside town, we had an Augustinian friary inside town and we had a hospital, so we had a real mixture of the different kind of subpopulations that you get in medieval life,” Mitchell tells the Guardian’s Nicola Davis.

Given the manner in which the archaeologists conducted the research, Mitchell says it’s possible they actually undercounted the number of cancer cases among the bodies studied. They did not analyze all of the bones in each skeleton, and they discounted bones with damage that could have been caused either by cancer or other sources, like bacterial infections and insects.

“Until now it was thought that the most significant causes of ill health in medieval people were infectious diseases such as dysentery and bubonic plague, along with malnutrition and injuries due to accidents or warfare,” says co-author Jenna Dittmar, also an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, in the statement. “We now have to add cancer as one of the major classes of disease that afflicted medieval people.”

The new findings add to scholars’ understanding of cancer, which has been a problem for humans—and other species—for a very long time. As Ed Cara reports for Gizmodo, the first recorded accounts of cancer date to more than 5,000 years ago, when an ancient Egyptian papyrus described the disease. At the same time, researchers know that cancer is more of a problem today than it was in the past. Today, the authors estimate, 40 to 50 percent of people in Great Britain have cancer in their bodies at time of death.

These higher modern levels likely reflect a number of factors. Industrial pollutants increase the chances of getting cancer, as does tobacco, which only became popular in Europe during the 16th century. Increased travel and population densities may also help spread viruses that damage DNA. Another major factor is rising lifespans. Many medieval people simply didn’t live to the ages when cancer becomes most common.

To pinpoint the causes of rising cancer rates over the centuries, reports CNN’s Katie Hunt, the researchers recommend additional study. Looking at bones from before and after smoking became popular in Europe, and before and after the Industrial Revolution, could offer clearer answers.

Regardless of the exact rates, those who got cancer in medieval times had very few medical treatment options. Though the period witnessed significant advances in surgery and knowledge of human anatomy, “this burst of Renaissance knowledge did not extend to cancer,” wrote Guy B. Faguet for the International Journal of Cancer in 2014.

Faguet added, “For instance, [French surgeon Ambroise] Paré called cancer Noli me tangere (do not touch me) declaring, ‘Any kind of cancer is almost incurable and … [if operated] … heals with great difficulty.’”

Mitchell tells the Guardian that medieval people may have treated their symptoms with poultices or cauterization, or, if they could afford them, anti-pain medications.

The archaeologist adds, “There was very little [doctors] would have had that was actually helpful.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)