Charles Dickens Lost His Last Christmas Turkey to a Freak Fire

A rediscovered letter reveals the famed author forgave the railway company that botched his holiday delivery

:focal(1294x672:1295x673)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/d7/0ad707de-67c6-4e46-91a6-b01de90a9d02/charles_dickens_circa_1860s.png)

On Christmas Eve of 1869, Charles Dickens dispatched an urgent message bound for Ross-on-Wye, a town in Herefordshire County, England.

“WHERE IS THAT TURKEY?” the all-caps message read. “IT HAS NOT ARRIVED!!!!!!!!!!!”

Sadly, the great Victorian novelist’s treasured bird, intended for his annual holiday feast, never arrived: As Dickens would later learn, it had been damaged beyond salvage by fire while under the care of the Great Western Railway Company. That means the famed author, who died just a few months later in June 1870, may have spent his last Christmas without a centerpiece, per a letter recently recovered by the National Railway Museum in York.

The revelation is one that tugs at the heartstrings, especially considering Dickens’ well-documented passion for holiday poultry. A Christmas Carol, which finds the more traditional goose swapped for a more “luxurious” turkey, helped shape “the image of Christmas as we know it today,” says museum curator Ed Bartholomew in a statement, as reported by Mike Laycock at the York Press.

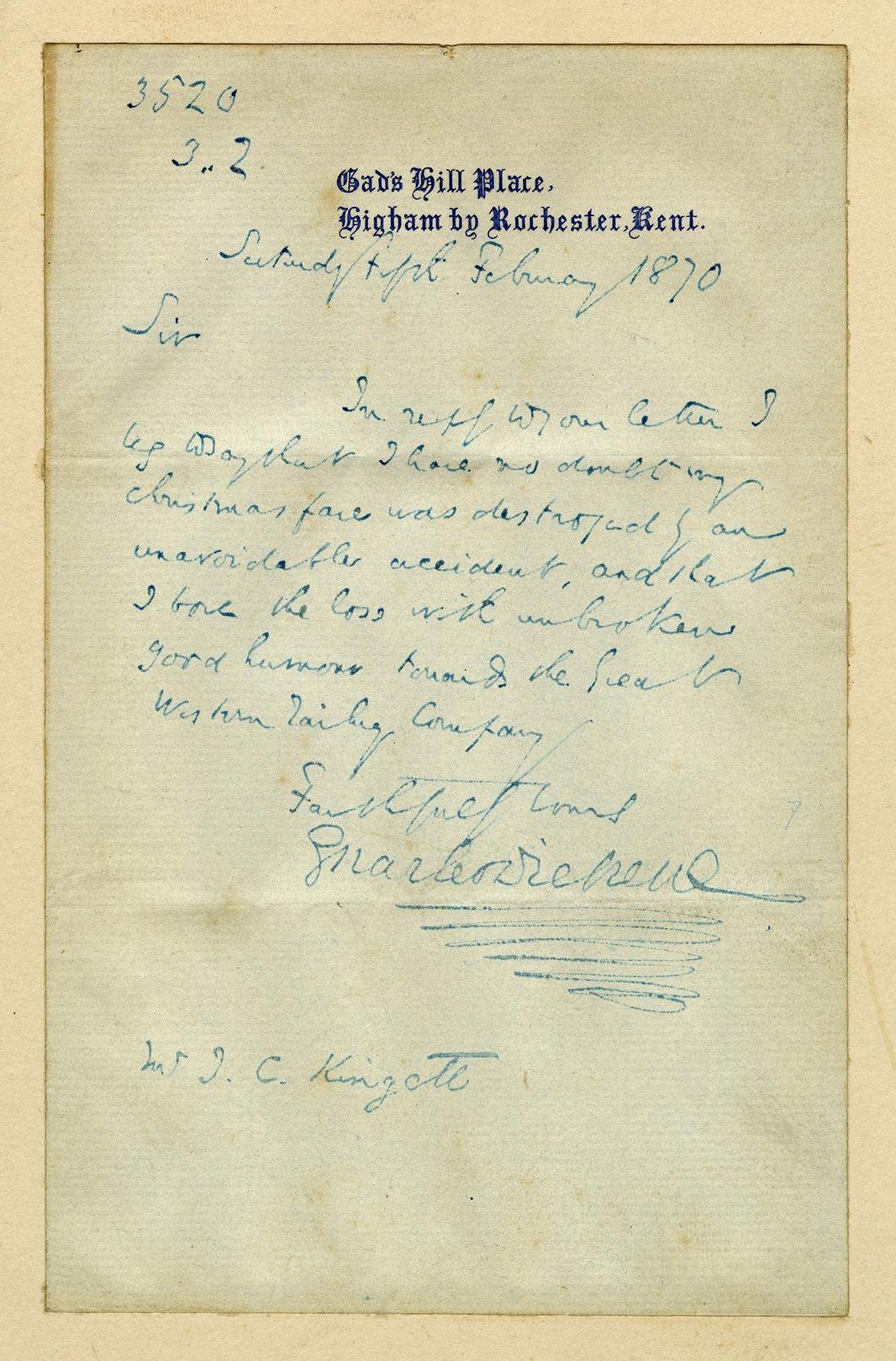

But as archive volunteer Anne McLean reveals in a blog post for the National Railway Museum, the jilted author seems to have taken his bereavement in stride. Upon receiving an apology and offer for compensation, Dickens penned a response, stating he had “no doubt my Christmas fare was destroyed by an unavoidable accident, and that I bore the loss with unbroken good humour towards the Great Western Railway Company.”

To be fair, the bird suffered a far worse fate. Shipped from the Ross-on-Wye home of Dickens’ tour manager George Dolby, the 30-pound turkey was wrapped in a parcel bursting with other Christmas treats. But en route to the Dickens family, the parcel was destroyed when the goods van carrying it caught fire somewhere between Gloucester and Reading.

By the time the flames had been extinguished, the turkey was far beyond well-done and in no state to be delivered to the railway company’s VIP client. Bizarrely, according to McLean, officials felt the charred remains were still fit enough to sell to the people of Reading at sixpence a serving.

As Christmas Day neared, the birdless Dickens felt his feathers had been ruffled. He contacted Dolby, who was distraught but could offer no help. It remains unclear, McLean reports, whether the Dickens family was able to scrounge up a substitute centerpiece.

In the following weeks, Great Western Railway Company Superintendent James Charles Kingett wrote to the customers affected by the fire, offering apologies and monetary compensation. (The latter offer apparently offended Dolby, who evidently thought no price tag could be put on Dickens’ distress.)

When Dickens responded with relative grace, Kingett kept the reply, which was published in 1908 in the Great Western Railway magazine before entering the collections of the National Railway Museum. There, it lay forgotten for several decades, but was recently rediscovered during a reappraisal and is now on display in the museum’s Highlights Gallery, reports Alison Flood for the Guardian.

McLean notes that the cause of that fateful, turkey-scorching fire remains mysterious. But she suggests the blaze may have been set by engine sparks meeting the vehicle’s wooden frame. At this time, no fowl play is suspected.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)