Why Did This Picasso Painting Deteriorate Faster Than Its Peers?

Study examines how animal glue, canvases, layers of paint and chemicals interacted to produce cracks in one work but not in others

:focal(577x371:578x372)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/12/d9129f34-ae50-4b1f-bf77-403e53d4d64f/fotonoticia_20210420172835_1200.jpeg)

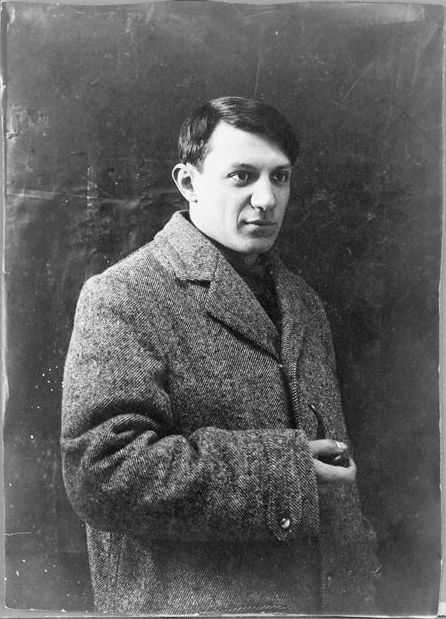

Innovative and eager to conserve scarce resources, the Spanish Cubist painter Pablo Picasso was no stranger to experimenting with unconventional materials. In the years since his death in 1973, conservators have found that the artists employed common house paint for a glossy effect, sprinkled sawdust into his paints and often recycled old canvases to save money on supplies.

As methods for studying the chemistry and microscopic structure of paintings advance, scientists continue to unlock new mysteries about the materials that Picasso used to craft his iconic works. Most recently, reports James Imam for the Art Newspaper, researchers led by Laura Fuster-López, a conservation expert at the Universitat Politècnica de València in Spain, published a three-year study of four similar 1917 Picasso paintings to determine why one deteriorated far more rapidly than the others. The international team detailed its findings in the journal SN Applied Sciences late last year.

Between June and November 1917, in the late stages of World War I, Picasso lived in Barcelona and often painted in the studio of his friend Rafael Martinez Padilla. Lacking a studio of his own, write the authors in the paper, the artist was forced to use new cotton canvases (instead of reusing old ones, as was his habit), as well as purchase animal glue, oil paints based on linseed and sunflower oil, brushes, and turpentine.

Picasso’s stay in Barcelona marked a pivotal point his career.

“Far from the oppressive climate in Paris, a city then at war, and from his Cubist circles, Picasso was able to work freely, searching for new forms of expression,” notes the Museu Picasso in Barcelona.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/e1/9be12c71-01ba-42e5-843d-210de124a0e6/4_opere_di_picasso_rid.png)

During his time in Spain, Picasso became involved with the Ballets Russes, an itinerant dance troupe led by Russian art critic Sergei Diaghilev. He helped design six ballets for Diaghilev, reported Karen Chernick for Artsy in 2018, and created at least four paintings inspired by the dancers: Hombre Sentado, or Seated Man in English; Woman on an Armchair; Man With Fruit Bowl; and an abstract portrait of Spanish singer and actress Blanquita Suárez.

Per a statement from Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Picasso stored the artworks in his family home upon his eventual return to Paris. In 1970, the works were donated to the Museo Picasso, where they remain today.

Despite being produced at the same time and housed in similar environments to the other three works, Seated Man has deteriorated far more rapidly than its peers—so much so that the painting had to undergo conservation efforts in 2016, according to the study.

“[Seated Man] shows signs of extreme cracking all over the painted surface,” Fuster-López tells the Art Newspaper. “It is like looking at a river bed once the water has dried up, with cracks and creases visible on the surface.”

As the statement notes, researchers worked to conserve the painting but “wanted to go deeper” to understand why its condition had worsened. The four paintings provided a relatively closed case study in which scientists could isolate specific variables that may have contributed to Seated Man’s marked degradation.

The team used non-invasive techniques, including X-ray fluorescence, infrared and reflectography, to determine that Picasso used a thicker weave of cotton canvas for Seated Man. He also applied a large amount of animal glue to the “ground” layers of the work. This high proportion of animal glue may have interacted with the tightly woven canvas to make Seated Man more susceptible to cracks in its paint—especially during periods of fluctuating humidity.

“Either the tendency of the canvas to shrink at high humidity or the significant internal stresses that hide glue builds-up at low humidity might have contributed to the extent of cracking observed,” the authors write in the study.

Interestingly, the scientists explain, areas of the canvas with higher proportions of white lead paint—such as the pale flesh and gray areas of Seated Man—may have been protected somewhat from cracking, as the metal ions found in white lead paint contributed to a stronger paint “film” on its surface.

Additionally, says co-author Francesca Izzo of Ca’ Foscari in the statement, she and her colleagues found that “in one case we believe that the artist experimented with the use of semi-synthetic paint that was not yet common in 1917.”

The analysis is one of the few of its kind to combine studies of the chemical composition of paint with observations of the mechanical damage wrought by interactions between the canvas and other layers of the painting, reports the Art Newspaper.

A potential area of note for future study is metal soaps, or compounds formed when fatty acids in paint’s binding agents react with lead and zinc in the pigment, as Lily Strelich wrote for Smithsonian magazine in 2019. These tiny bumps, known informally as “art acne,” appeared on the Picasso painting studied and have previously popped up on works by Rembrandt, Georgia O’Keeffe, Piet Mondrian, Vincent van Gogh and other prominent painters.

The statement notes, “Metal soaps can cause clearly visible damage, both on an aesthetic level and in terms of chemical and mechanical stability.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)