Children Are Susceptible to Robot Peer Pressure, Study Suggests

When robots provided incorrect answers in social conformity test, children tended to follow their lead

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/bc/6bbc5531-56f1-455c-87b2-f0da50be7921/univ_plymouth_beep_boop.jpg)

It sounds like a plot from Black Mirror: Students are asked to identify matching objects, but when a robot chimes in with an obviously wrong answer, some kids repeat what the bot says verbatim instead of tapping into their own smarts. But this isn't science fiction—a new study published in Science Robotics suggests kids easily succumb to peer pressure from robots.

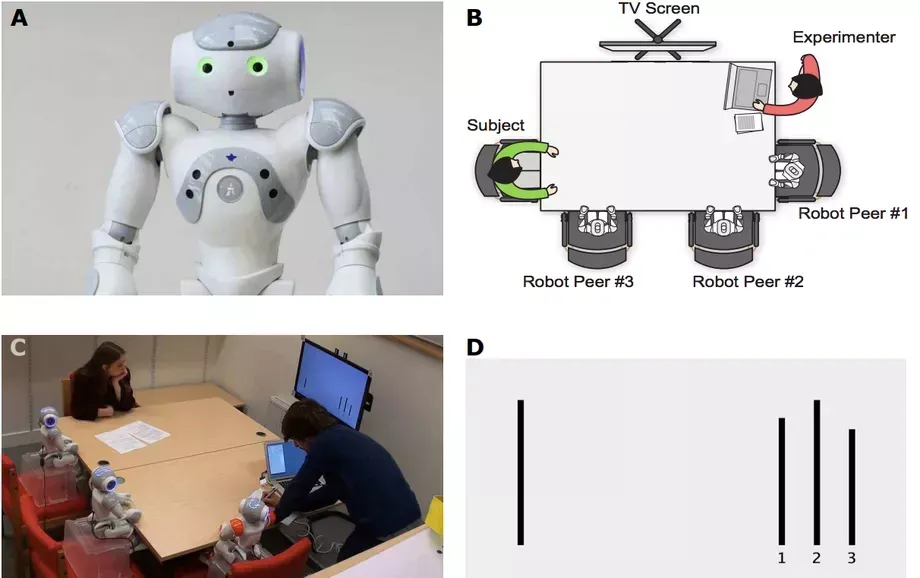

Discover’s Bill Andrews reports that a team of German and British researchers recruited 43 children aged between 7 and 9 to participate in the Asch experiment, a social conformity test masquerading as a vision exam. The experiment, which was first developed during the 1950s, asks participants to compare four lines and identify the two matching in length. There is an obviously correct answer, as the lines are typically of wildly varying lengths, and when the children were tested individually, they provided the right response 87 percent of the time.

Once robots arrived on the scene, however, scores dropped to 75 percent.

“When the kids were alone in the room, they were quite good at the task, but when the robots took part and gave wrong answers, they just followed the robots,” study co-author Tony Belpaeme, a roboticist at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom, tells The Verge’s James Vincent.

In the new testing environment, one volunteer at a time was seated alongside three humanoid robots. Although the lines requiring assessment remained highly distinguishable, child participants doubted themselves and looked to their robot counterparts for guidance. Of the incorrect answers that the children provided, 74 percent matched those provided by the robots word for word.

Alan Wagner, an aerospace engineer at Pennsylvania State University who was not involved in the new study, tells The Washington Post’s Carolyn Y. Johnson that the implacable faith humans often place in machines is known as “automation bias.”

“People tend to believe these machines know more than they do, have greater awareness than they actually do,” Wagner notes. “They imbue them with all these amazing and fanciful properties.”

The Verge’s Vincent writes that the researchers conducted the same test on a group of 60 adults. Unlike the children, these older participants stuck with their answers, refusing to follow in the robots’ (incorrect) footsteps.

The robots’ demure appearance may have influenced adult participants’ lack of faith in them, Belpaeme explains.

“[They] don’t have enough presence to be influential,” he tells Vincent. “They’re too small, too toylike.”

Participants questioned at the conclusion of the exam verified the researchers’ theory, stating that they assumed the robots were malfunctioning or not advanced enough to provide the correct answer. It’s possible, Belpaeme notes, that if the study were repeated with more authoritative-looking robots, adults would prove just as susceptible as children.

According to a press release, the team’s findings have far-reaching implications for the future of the robotics industry. As “autonomous social robots” become increasingly common in the education and child counseling fields, the researchers warn that protective measures should be taken to “minimise the risk to children during social child-robot interaction.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)