Christie’s Will Be the First Auction House to Sell Art Made by Artificial Intelligence

Christie’s will sell the work from Paris-based art collective Obvious, which created ‘Portrait of Edmond Belamy’ with the machine-learning algorithm GAN

At first glance, portraits of the Belamy family seem to exemplify life in the upper echelons of French society. The haughty features of patriarch Le Comte De Belamy are framed by a voluminous white powdered wig, while the dynastic matriarch, La Comtesse, oozes wealth in her colorful silk attire. Skipping ahead several generations, you’ll encounter Madame De Belamy, whose tightly coiffed hair is tucked inside a blue hat rendered in Impressionistic strokes, and her son Edmond, a comparatively dour-looking young man clad almost entirely in black.

But there’s a catch to this story of generational greatness: In addition to being wholly fictional, the Belamy family hovers in that amorphous space between artificial intelligence and art. Although its members’ names and places in the family tree were assigned by Obvious, a Paris-based art collective, their likenesses are the brainchild of Generative Adversarial Networks, a machine learning algorithm better known by the acronym GAN.

Now, Naomi Rea writes for Artnet News, the youngest member of the family—as depicted in “Portrait of Edmond Belamy”—is set to make history as the subject of the first AI-produced artwork sold by an auction house.

A canvas print of Obvious’ (and GAN’s) creation will be included in Christie’s late October auction of Prints and Multiples, the New York-based auction house reports. It remains to be seen how bidders will react to the AI work, but Obvious remains optimistic, citing an estimated sale price of €7,000 to €10,000, or roughly $8,000 to $11,500.

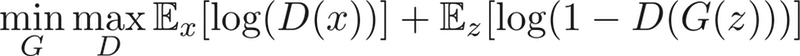

Hugo Caselles-Dupré, one of Obvious’ three co-founders, tells Christie’s Jonathan Bastable that GAN consists of two parts: the Generator, which produced images based on a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th and 20th centuries, and the Discriminator, which attempts to differentiate manmade and AI-generated works.

“The aim is to fool the Discriminator into thinking that the new images are real-life portraits,” Caselles-Dupré says. “Then we have a result.”

According to an essay posted on Obvious’ Medium page, GAN analyzes thousands of images to learn the basic features of portraiture. The subsequent AI-generated portraits are both similar to the images in the original data source and singularly unique. A different image is rendered with every execution of the algorithm.

“This reflects a human creativity feature: We will never create twice the same thing,” Obvious writes.

Obvious, a three-man team made up of Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel and Gauthier Vernier, owes much to American AI researcher Ian Goodfellow, who developed the GAN algorithm in 2014. As Time’s Ciara Nugent notes, the rough French translation of “Goodfellow”—bel ami—provided inspiration for the fictional family’s name.

The Belamy portraits are painted in a semi-realistic style, their blurred details creating an overarching impression of motion. In the bottom right corner of the canvases, the artist’s signature is replaced by an intimidating mathematical equation:

Such proclamations of authorship are a central concern in the art world’s AI debate. Skeptics of the new technology doubt that machines can produce art, which has long been viewed as a uniquely human activity. If an AI researcher designs and executes an algorithm, who is the end product’s true creator: human artist or machine? And, most importantly, if robots can create art, where does that leave humans?

There are no easy answers to these questions, but as Rose Eveleth, host of the future-centric podcast Flash Forward, argued in a recent episode, this isn’t the first time humans have felt threatened—or entranced—by machine-made art.

Swiss-born watchmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz launched the golden age of automata, or kinetic sculptures designed to mimic human movement, with “The Writer.” The 1770s doll was made of 6,000 moving parts that allowed it to scribble out an array of messages, dip a quill into an inkwell, and blink with unseeing eyes.

At the time, philosophers were engaged in a heated battle over what it meant to be alive, Eveleth notes. While we don't think of today's AI as a living organism, modern technology does continue to raise existential questions about what it means to be human. Consider a more recent innovation: the camera. It also posed some philosophical problems, Caselles-Dupré tells Time’s Nugent.

“Back then, people were saying that photography is not real art and people who take pictures are like machines,” he says. “And now we can all agree that photography has become a real branch of art.”

By including “Portrait of Edmond Belamy” in its fall sale, Christie’s isn’t offering a final ruling on the value of AI art. Still, the decision is sure to attract ire, elation and, if the sale is successful, newfound faith in the burgeoning medium.

“I’ve tended to think human authorship was quite important—that link with someone on the other side,” Richard Lloyd, head of Christie’s Prints and Multiples department, tells Nugent. “But you could also say art is in the eye of the beholder. If people find it emotionally charged and inspiring, then it is. If it waddles and it quacks, it’s a duck.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/3c/eb3cf811-df19-4018-9c71-90d78bb7c7d9/edmond.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)