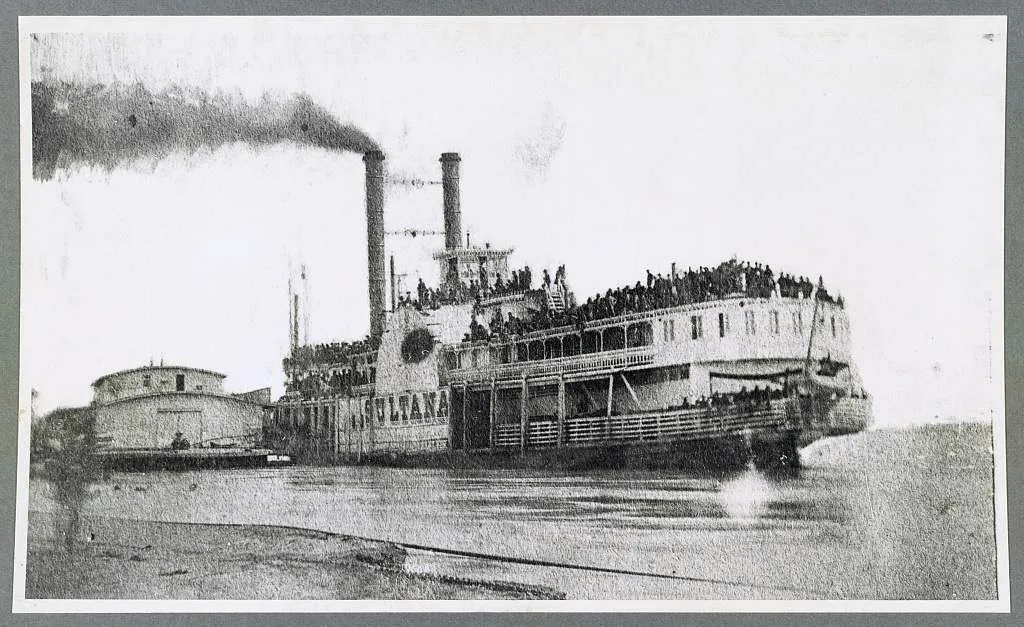

This Civil War Boat Explosion Killed More People Than the ‘Titanic’

The ‘Sultana’ was only legally allowed to carry 376 people. When its boilers exploded, it was carrying 2,300

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/32/28328031-3d8f-4c3c-aae1-32e4627e8bde/steamboat.jpg)

The Civil War was the deadliest conflict in U.S. history. But one of its lesser-known gory episodes actually happened after the war ended, as Union prisoners of war made their ways home—or tried to.

On this day in 1865, a steamboat carrying 2,300 recently released Union POWs, crew and civilians sank after several of its steam boilers exploded. An estimated 1,800 people died, of causes ranging from steam burns to drowning, making the explosion of the Sultana the deadliest maritime disaster in U.S. history—worse than the Titanic. Although the disaster got little press in its own time and remains little-known today, the city of Marion, Arkansas has ensured it is not forgotten.

For a nation saturated by news of war and death, writes Stephen Ambrose for National Geographic, one more catastrophe just wasn’t that newsworthy. “April 1865 was a busy month,” Ambrose writes. Confederate troops under Robert E. Lee and Joseph Johnson surrendered. Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and his assassin caught and killed. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured, ending the Civil War.

The public’s news fatigue was at a high, and the death of fewer than 2,000 people—stacked up against the roughly 620,000 soldiers who died during the Civil War, to say nothing of civilians—didn’t register on a national scale, Ambrose writes. The disaster was relegated to the back pages of Northern newspapers.

For the survivors of the Sultana and the communities on the banks of the Mississippi near the explosion, though, the disaster was hard to miss, writes Jon Hamilton for NPR. The rescue effort that followed the disaster “included Confederate soldiers saving Union soldiers they might have shot just weeks earlier,” he writes.

“Many Sultana survivors ended up on the Arkansas side of the river, which was under Confederate control during the war. And many of them were saved by local residents,” Hamilton writes. Those residents included John Fogleman, “an ancestor of the city of Marion's current mayor, Frank Fogleman.”

The 1865 Foglemans were able to rescue about 25 soldiers and sheltered them, Hamilton writes. Newspaper accounts from the period also point to a Confederate soldier named Franklin Hardin Barton, who had been involved in the river patrol, saving several of the soldiers he would have been obliged to fight on the river just a few weeks earlier. And those aren't the only examples.

Like most Civil War events, the explosion of the Sultana has attracted its share of historical sleuths. Many place the blame for the horrific disaster on a profit-minded captain who didn’t care if pesky regulations got in the way, writes Hamilton. The steamboat was only registered to carry 376 people, writes Ambrose. It was carrying more than six times that number.

One Sultana researcher told Hamilton that it’s clear J. Cass Mason “had bribed an officer at Vicksburg to ensure that he would get a large load of prisoners.” According to Jerry Potter, the damaged boiler had already received a half-hearted repair. The mechanic who did the work “told the captain and the chief engineer the boiler was not safe, but the engineer said he would have a complete repair job done when the boat made it to St. Louis," Potter says.

But the boat didn’t make it, and locals are still haunted by the tragedy. For the 150th anniversary of the disaster in 2015, the city of Marion, Arkansas created a museum that shows how the Sultana explosions happened and memorializes those aboard.