Collection of Alexander Hamilton’s Documents Can Now Be Viewed Online

Among them are Hamilton’s first report as Secretary of Treasury, and a steamy love letter to his wife

:focal(380x304:381x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/d9/bbd92903-8c61-4858-bdba-cc46b9448895/760px-alexander_hamilton_portrait_by_john_trumbull_1806.jpg)

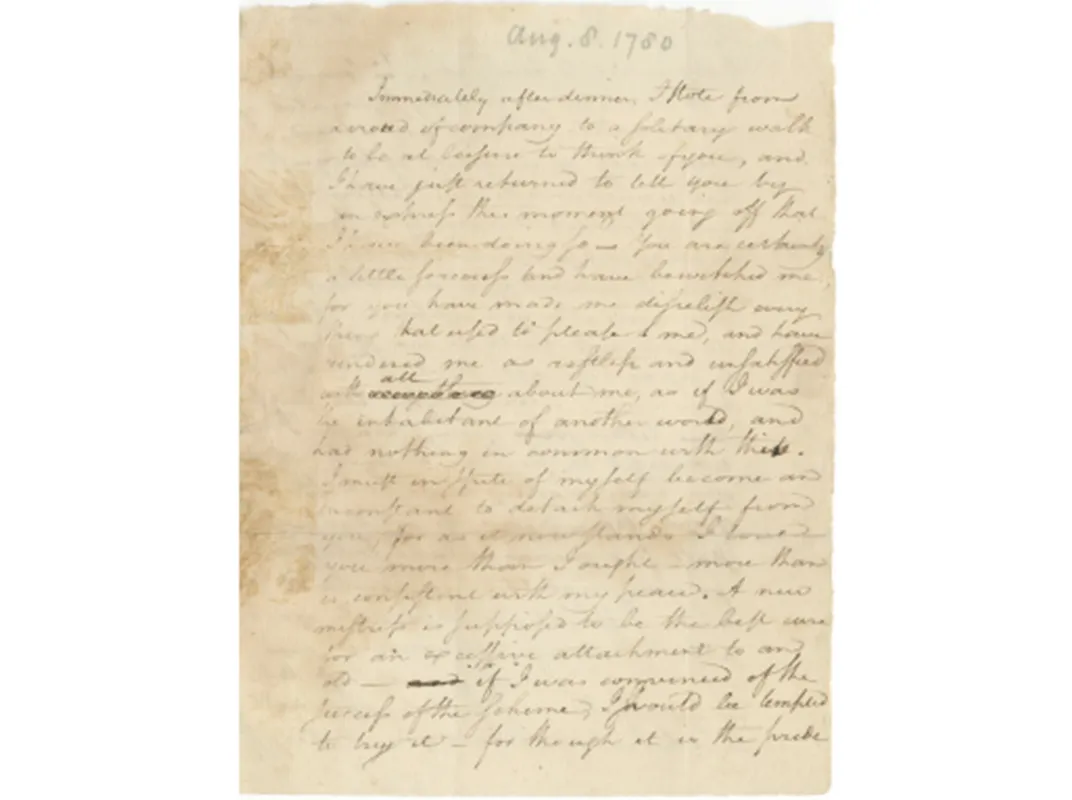

“You are certainly a little sorceress and have bewitched me,” Alexander Hamilton wrote to Elizabeth Schuyler, the woman who would become his wife, in August of 1780. It was the height of the Revolutionary War, and Hamilton was in the midst of authoring a plan for retaking New York from the British. But he seems to have been rather distracted.

“You have made me disrelish every thing that used to please me,” he wrote to Schuyler, “and have rendered me as restless and unsatisfied with all about me, as if I was the inhabitant of another world.”

This steamy love letter is included in a trove of Hamilton documents recently put up for sale, Olivia B. Waxman reports for Time. Seth Kaller, a historic document dealer, is offering a collection of letters, pamphlets, articles, and imprints that were written by or about everyone’s favorite Founding Father. These documents, which together have been valued at $2.4 million, are temporarily on display at the Antiquarian Book Fair in New York. They can also be viewed online.

Among the many fascinating items included in the collection are Hamilton’s first report to Congress as Secretary of Treasury, and a 1792 letter to George Washington, in which Hamilton accuses Thomas Jefferson of subverting the government. Hamilton and Jefferson were ideological rivals, who frequently tussled over foreign and economic policy. In another letter to an unknown recipient, written after George Washington declined to serve a third term, Hamilton expressed his firm view that he would be happy to support any candidate for president—as long as it was not Jefferson.

“Tis all important to our Country that his successor shall be a safe man,” he wrote. “But tis far less important, who of many men that may be named shall be the person, than that it shall not be Jefferson.”

Also included in the collection is Hamilton’s blistering Reynolds Pamphlet, in which he admitted to having an affair with a young woman named Maria Reynolds, but denied charges of financial corruption. As Angela Serratore explains in Smithsonian, Hamilton felt compelled to publish the pamphlet after “Republican and proto-muckraker” James Callender accused him of both sexual depravity and illegal speculating with government funds.

In addition to its political resonance, the collection shines a light on Hamilton’s character. Several letters, for instance, testify to his hot-headed propensity for starting duels—“a habit that did not end well,” Kaller’s website notes. Indeed, the collection includes reports on the Hamilton-Burr duel, which brought an end to Hamilton’s life.

But a piece of Hamilton remains with us—quite literally. One of the stranger items now available for sale is a lock of Hamilton’s hair, mounted on cardstock and set behind glass. This little loop of hair, the catalogue explains, consists “of approximately 20 auburn strands, with a few graying or whitening.”