Five Things to Know About the 1876 Presidential Election

Lawmakers are citing the 19th-century crisis as precedent to dispute the 2020 election. Here’s a closer look at its events and legacy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/57/4a57643f-c2e1-4206-b6ce-d6be791ed6be/master-pnp-cph-3b40000-3b43000-3b43600-3b43606u.jpg)

On election night, Republican presidential candidate and Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes was losing so badly that he prepared his concession speech before turning in for the night. His party chairman went to bed with a bottle of whiskey. “We soon fell into a refreshing sleep,” Hayes later wrote in his diary about the events of November 7, 1876. “[T]he affair seemed over.”

But after four months of fierce debate and negotiations, Hayes would be sworn into office as 19th president of the United States. Historians often describe his narrow, controversial win over Democrat Samuel J. Tilden as one of the most bitterly contested presidential elections in history.

This week, the events of the 1876 presidential race have once again come under scrutiny. As Jason Slotkin reports for NPR, a group of Senate Republicans announced that they will vote to reject electors from states they consider disputed if Congress does not form a commission to investigate their claims of voter fraud. Though these claims are unfounded, the lawmakers cite the 1876 election as precedent for their actions.

In 1876, “the elections in three states—Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina—were alleged to have been conducted illegally,” the senators write in a statement. “In 1877, Congress did not ignore those allegations, nor did the media simply dismiss those raising them as radicals trying to undermine democracy. … We should follow that precedent.”

The comparison drew criticism from scholars, including Penn State University political scientist Mary E. Stuckey, who tells the Dallas News that it’s “historically misleading.” For starters, the electoral college result was incredibly tight: Just one electoral vote separated the candidates. What sets the election of 1876 apart from the election of 2020 the most is that lawmakers had ample evidence of widespread voter repression against newly enfranchised African Americans in the post-Confederacy South—and therefore good reason to doubt the veracity of election results. Historian Kate Masur, also speaking with the Dallas News, says that “there was not a clear cut result being delivered to Congress of what had happened at the state level, and so that’s why Congress decided it was a huge crisis.”

The 1876 election also has a fraught legacy: After months of bitter fighting, lawmakers made a fateful compromise that put Hayes in office by effectively ending Reconstruction, leading to a century of intensified racial segregation in the South.

Here are five key things to know about the presidential election of 1876.

1. The candidates were a reform-minded Democrat and a Reconstructionist Republican.

Hayes, a lawyer, businessman and abolitionist, was a war hero who had fought in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. He went on to serve in Congress and later as Ohio’s governor, where he championed African American suffrage, as Robert D. Johnson writes for the Miller Center of Public Affairs.

Running on the Democratic ticket was Tilden, an Ivy League graduate who appealed to voters with a successful anti-corruption track record during his tenure as New York’s governor. In the years since the Civil War ended in 1865, Democrats, whose voter base resided in the former Confederacy, had been partly shut out of the political sphere; now, with Republican Ulysses S. Grant facing charges of corruption, Tilden’s reform-minded candidacy seemed like a well-timed opportunity for Democrats to regain political power, as Gilbert King wrote for Smithsonian magazine in 2012.

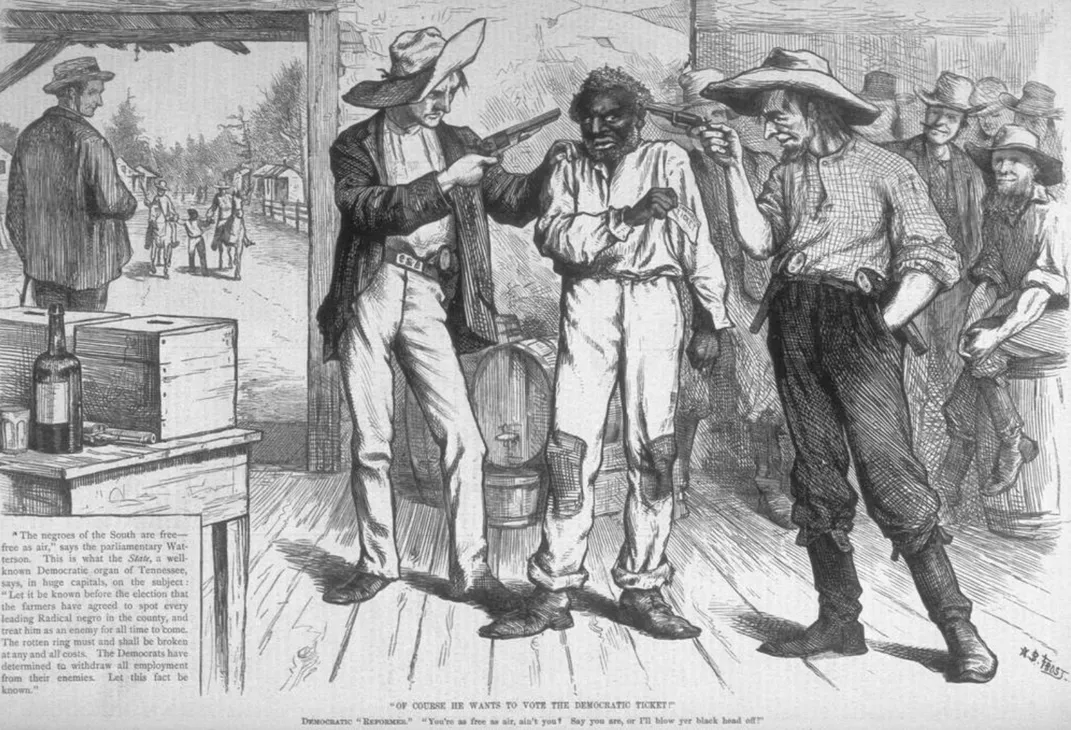

2. Voter suppression was rampant in the post-Confederacy South.

Many historians argue that if votes had been counted accurately and fairly in Southern states, Hayes might have won the 1876 election outright. “[I]f you had a fair election in the south, a peaceful election, there’s no question that the Republican Hayes would have won a totally legitimate and indisputable victory,” Eric Foner, a preeminent historian of the Civil War and Reconstruction, told the Guardian’s Martin Pengelly in August.

But the election process in Southern states was rife with voter fraud—on the part of both parties—and marked by violent voter suppression against black Americans. Under Reconstruction, African Americans had achieved unprecedented political power, and new federal legislation sought to provide a modicum of economic equality for newly enfranchised people.

In response, white Southerners rebelled against African Americans’ newfound power and sought to intimate and disenfranchise black voters through violence, Ronald G. Shafer reported in November for the Washington Post. In the months during and preceding the election, mobs known as “red shirts” patrolled voting stations and threatened, bribed and murdered black voters.

3. Election results were a mess.

Just a few days following the election, Tilden appeared poised to narrowly clinch the election. He had captured 51.5 percent of the popular vote to Hayes’s 48 percent, a margin of about 250,000 votes.

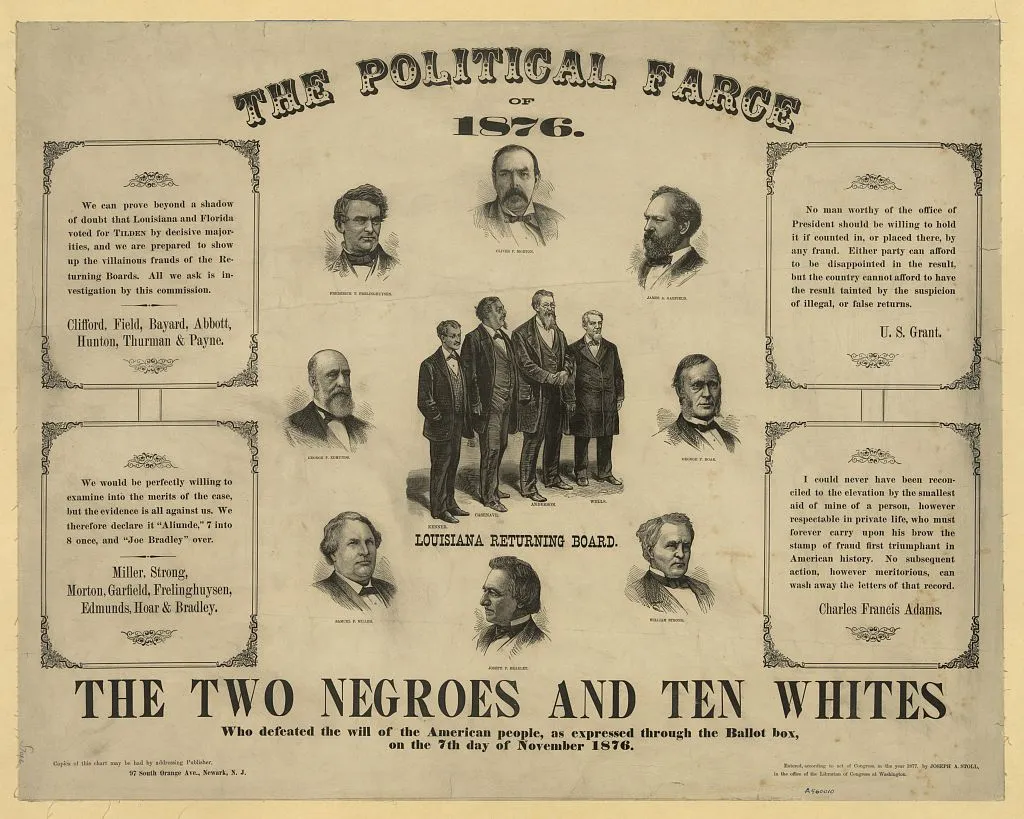

Tilden needed just one more vote in the electoral college to reach the 185 electoral votes necessary for the presidency. Hayes, meanwhile, had 165. Election returns from three Republican-controlled Southern states—Louisiana, Florida and South Carolina—were divided, with both sides declaring victory.

Hayes’ proponents realized that those contested votes could sway the election. They seized the uncertainty of the moment, encouraging Republican leaders in the three states to stall, and argued that if black voters hadn’t been intimidated away from the polls—and if voter fraud hadn’t been as rampant—Hayes would have won the contested states. With a Republican-controlled Senate, a Democrat-controlled House and no clear presidential winner, Congress was thrown into chaos.

4. Secret deals, backroom debates and new rules decided the election.

In an unprecedented move, Congress decided to create an extralegal “Election Commission” composed of five senators, five House members and five Supreme Court justices. In late January, the commission voted 8-7 along party lines that Hayes had won all the contested states, and therefore the presidency, by just one electoral vote.

Furious Democrats refused to accept the ruling and threatened a filibuster. So, in long meetings behind closed doors, Democrats and Hayes’ Republican allies hashed out what came to be known as the Compromise of 1877: the informal but binding agreement that made Hayes president on the condition that he end Reconstruction in the South.

Finally, just after 4 a.m. on March 2, 1877, the Senate president declared Hayes the president-elect of the United States. Hayes—dubbed “His Fraudulency” by a bitter Democratic press—would be publicly inaugurated just two days later.

Ten years later, the debacle would also result in a long-overdue law: the Electoral Count Act of 1887, which codified electoral college procedure, as Shafer reports for the Post.

5. Hayes secured his win by agreeing to end Reconstruction.

Just two months after his inauguration, Hayes made good on his compromise and ordered the removal of the last federal troops from Louisiana. These troops had been in place since the end of the Civil War and had helped enforce the civil and legal rights of many formerly enslaved individuals.

With this new deal, Hayes ended the Reconstruction era and ushered in a period of Southern “home rule.” Soon, a reactionary, unfettered white supremacist rule rose to power in many Southern states. In the absence of federal intervention over the next several decades, hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan flourished, and states enacted racist Jim Crow laws whose impacts continue to be felt today.

“As a result,” wrote King for Smithsonian, “the 1876 presidential election provided the foundation for America’s political landscape, as well as race relations, for the next 100 years.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)