Why a Newly Approved Plan to Build a Tunnel Beneath Stonehenge Is So Controversial

Proponents say the tunnel will reduce noise and traffic, but some archaeologists fear that it will damage artifacts at the historic site

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/09/7009091e-88dd-4da7-9db3-9cc0fd4b9285/stonehengemonumentwitha303inbackground_highres.jpg)

Every year, more than one million tourists flock to Stonehenge to marvel at the hulking rock formations erected by Neolithic builders roughly 5,000 years ago. But some visitors find themselves faced with a decidedly less awe-inspiring scene: a noisy two-lane highway, often choked with cars, that cuts straight through the grassy slopes surrounding the ancient monument.

After decades of debate and planning, the British government has finally approved a proposal to build a tunnel moving this road, the A303, underground. The United Kingdom’s transport secretary, Grant Shapps, greenlit the $2.25-billion (£1.7 billion) project last week despite strong objections from archaeologists and preservationists, who fear that construction will result in the loss of hundreds of thousands of artifacts, report Gwyn Topham and Steven Morris for the Guardian.

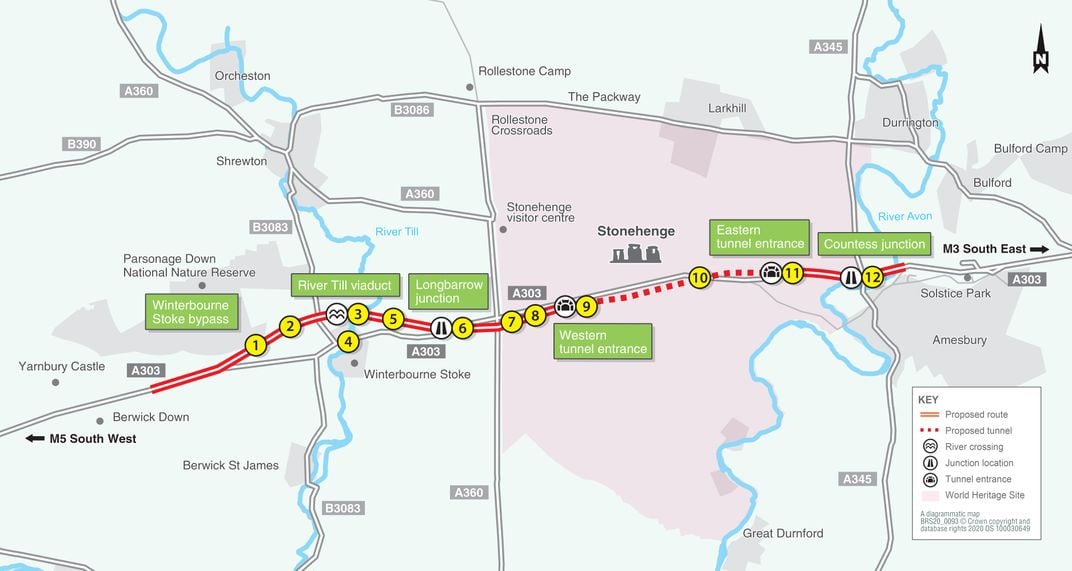

Currently, the section of the A303 by Stonehenge supports about twice as much traffic as it was designed to accommodate. According to Highways England, the government company set to construct the road, the new plan will create an eight-mile stretch of dual carriageway that travels through a tunnel for a two-mile stretch as it passes the prehistoric stones.

The tunnel will stand about 55 yards farther away from Stonehenge than the existing A303, reports Brian Boucher for artnet News. According to proposals on Highway England’s website, tunnel entrances will be disguised with grassed-over canopies and will remain “well out of sight” of Stonehenge.

Supporters of the plan argue that the tunnel will reduce the noise and smells of a busy road while offering Stonehenge visitors a relatively unimpeded view of their surroundings. Officials say the expanded lanes will also decrease traffic bottlenecks—something this stretch of road is notorious for, according to Roff Smith of National Geographic.

“Visitors will be able to experience Stonehenge as it ought to be experienced, without seeing an ugly snarl of truck traffic running right next to it,” Anna Eavis, curatorial director for English Heritage, the charity that cares for the historic site, tells National Geographic.

Kate Mayor, CEO of English Heritage, voiced her support for the plan in a statement provided to NPR’s Reese Oxner.

“Placing the noisy and intrusive A303 within a tunnel will reunite Stonehenge with the surrounding prehistoric landscape and help future generations to better understand and appreciate this wonder of the world,” says Mayor.

Archaeologists, however, contend that the tunnel’s construction could destroy valuable archaeological evidence yet to be discovered in the site’s topsoil. Mike Parker Pearson, a scholar of British later prehistory at University College London and a member of Highway England’s independent A303 scientific committee, tells the Observer’s Tom Wall that the project’s contractors will only be expected to retrieve and preserve 4 percent of artifacts uncovered in ploughed soil during the construction process.

“We are looking at losing about half a million artifacts—they will be machined off without recording,” says Pearson, who is part of a team that has been excavating a site near the proposed western tunnel entrance since 2004.

He adds, “You could say ‘they are just a bunch of old flints’ but they tell us about the use of the Stonehenge landscape over the millennia.”

Experts also assert that the region could hold many new surprises: This summer, archaeologists discovered a circle of enormous ancient pits encircling Stonehenge—a find that “completely transformed how we understand [the] landscape,” lead researcher Vincent Gaffney of the University of Bradford told the New York Times’ Megan Specia in June. Now, Gaffney warns that future finds of this magnitude could be lost due to construction work.

“Remote sensing has revolutionized archaeology and is transforming our understanding of ancient landscapes—even Stonehenge, a place we thought we knew well,” he says to National Geographic. “Nobody had any idea these were there. What else don’t we know?”

David Jacques—director of the Blick Mead archaeological dig, which has unearthed crucial information about the humans who lived near Stonehenge as early as 8,000 B.C.— tells the Guardian that the decision to build the tunnel is “absolutely gut-wrenching” and “a head-bangingly stupid decision.”

Critics of the construction project include the Campaign to Protect Rural England, the British Archaeological Trust and the Stonehenge Alliance, which launched a petition calling to “save Stonehenge … from the bulldozers.” (The call to action garnered more than 150,000 signatures.) Additionally, Arthur Pendragon, a prominent modern-day druid, tells the Observer that he plans to lead protests against the construction.

In 2019, Unesco’s World Heritage Committee condemned the plan, saying it would have an “adverse impact” on the “outstanding universal value” of the site. As BBC News reported at the time, the group called for the creation of longer tunnel sections that would “reduce further the impact on the cultural landscape.”

English Heritage and Highways England say that the project’s staff will take extensive steps to ensure that the historic land and its treasures are disturbed as little as possible during construction.

“We already have a good idea of what’s there and there will be a full program of mitigation to ensure that any archaeology that isn’t preserved in situ is fully recorded,” Eavis tells the Observer.

Speaking with the Observer, Derek Parody, the project’s director, adds, “We’re confident that the proposed scheme presents the best solution for tackling the longstanding bottleneck on this section of the A303, returning the Stonehenge landscape to something like its original setting and helping to boost the south-west economy.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)